The Scourge of Dropping Out

Keeping truants in school requires broad collaboration—and a willingness on the part of all concerned to ask, Am I part of the problem?

In 2003, as the director of the immigrant organization One Lowell, I was approached by a Cambodian woman whose son was being dropped from the school roll because of multiple absences. He was not being given the opportunity to make up the absences or being invited back to school the following year. His housemaster, or assistant principal, asked his mother to take responsibility by signing him out of school although he was over the age of 16, the legal age for dropping out in Massachusetts.

Every morning the mother had dropped her son off at school. She'd received no communication from the school warning of her son's truancy. I spoke with school officials and arranged for the housemaster to meet with the mother, the son, and a translator. The upshot was that the student was allowed to return to school the following year. He graduated from high school and later from our local community college.

The incident gave me insight into the difficulties parents face advocating for their children in public schools, especially parents with limited English.

When Students Drop Out

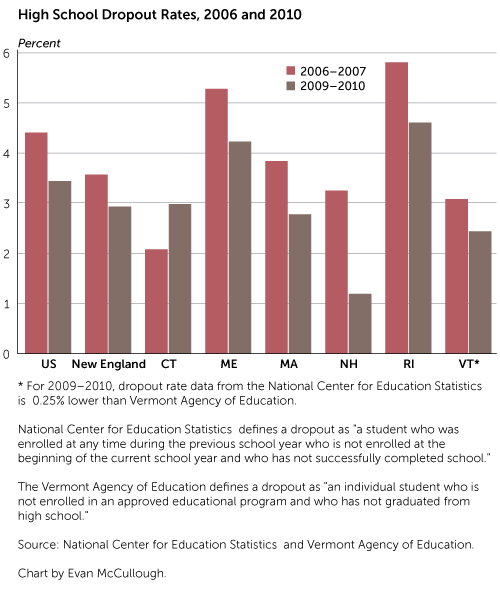

According to the Center for Labor Market Studies at Northeastern University, an estimated 16 percent of all 16-to-24-year-olds nationwide-nearly one out of six-dropped out of high school in 2007. (See "High School Dropout Rates.") Roughly a million of those enrolled would eventually drop out. The total number of dropouts between the ages of 16 and 24 was nearly 6.2 million that year-60 percent male and 30 percent Hispanic. Among all men in that age group, nearly one out of every five dropped out of school.[1]

The Cost to Individuals

When students drop out, they often end up engaging in antisocial behaviors or developing mental health problems. Their lack of job skills may handicap them permanently and even negatively impact their children and future generations.

The Center for Labor Market Studies has looked at dropping out and its impact on society. Researchers have found that, on average, 54 percent of U.S. dropouts aged 16 to 24 were jobless during 2008. Among others in the same age bracket, 32 percent of those who graduated high school were jobless, 21 percent of those with one to three years of postsecondary schooling, and only 13 percent of college graduates.[2]

The mean annual earnings of U.S. dropouts under age 25 were $8,358 in 2007. Young people with a bachelor's or advanced degree had mean earnings of $24,797-three times higher. Young female dropouts were nearly nine times as likely to be single mothers as young women with undergraduate degrees. A high share of young, unwed mothers were dependent on government assistance and in-kind transfers to support themselves and their children. Moreover, children of dropouts were at greater risk for poor nutrition and health, lower cognitive skills, and poor schooling outcomes than children of parents with at least a high school diploma.

The Cost to Society

Dropouts, and later their children, are not the only ones who suffer. Their loss is ours. Earning an estimated $400,000 less over their lifetimes means less tax revenue collected and higher costs to governments for health care and social care, which sometimes includes incarceration. Each dropout will cost taxpayers more than $292,000. In contrast, simply having a high school diploma could amount to fiscal benefits of more than $287,000 per person.

Another concern is that those with no diploma are incarcerated at a rate more than 63 times higher than for young, four-year college graduates. And incarceration is expensive. The annual cost per capita in Massachusetts alone was $43,025 in 2006.[3] When separated by gender, nearly 1 of every 10 young male high school drop-outs was institutionalized on a given day in 2006-2007 versus fewer than 1 of 33 high school graduates, 1 of 100 young men with some postsecondary schooling, and only 1 of 500 who held a bachelor's degree or higher. Needless to say, offenders also are costly to victims, through damaged or stolen property, personal injury, or lost wages. Victims may also suffer hidden costs, such as mental-health services and child-care expenses when they can't care for their children.

Why They Drop Out

The path to dropping out often starts in elementary school. Most students who drop out could have succeeded. In a 2006 Gates Foundation study of 457 recent dropouts nationwide, 88 percent had passing grades, and 62 percent had C's and above. Seventy percent were confident they could have graduated from high school.[4] About the same percentage said they weren't motivated or inspired to work hard in high school, and nearly half said that a major reason for dropping out was that classes were uninteresting. Dropouts, particularly those dropouts with high grade point averages, reported being bored and disengaged. Forty-five percent said that they started high school poorly prepared by their earlier schooling and that the supports that could have helped weren't available. Nearly a third said they left to get a job, 26 percent said that becoming a parent caused them to leave school, and 22 percent said they had to care for a family member. Forty-three percent reported missing so many days of school that they couldn't catch up; 35 percent reported that they couldn't keep up.

In 2006, the Massachusetts Department of Education (MDOE) organized focus groups of students representing dropouts, or those at risk of dropping out, and found results similar to the Gates study. Participants specifically addressed problems with school staff, including a perceived lack of help, recommendations to quit school, lack of respect, and poor student-teacher relationships. Participants also addressed issues such as skipping school, problems with mental, emotional, or physical health, lack of parental support, too many drug or partying influences, and family and personal problems.[5] In the Gates Foundation study, only 59 percent reported that their parents had been involved with their schooling, and of the parents who had been involved, half were involved "mainly for discipline reasons." Nearly half of the participants said that their parents' work schedules had prevented them from knowing what was going on in school. Only 47 percent reported that their parents had ever been contacted by the school about absenteeism.

The MDOE study referenced a survey completed in 2005 by 105 district leaders asking their opinions.[6] Nearly half of respondents stated that students left school because of a lack of parental support, disruptive family life, a death in the family, education not being valued in the family, parents requesting the student to discontinue education, and unspecified personal or family issues. District leaders also cited lack of academic success (46 percent), frequent truancy (40 percent), and economic needs such as full-time employment, supporting a family, and doing job training (40 percent). Similar results were found in self-assessments by 11 Massachusetts school districts.

What's the Solution?

Although students and educators found similar reasons for students dropping out, they don't appear to agree on the changes that need to occur. Having worked professionally with youth at high risk of truancy in the Lowell Public Schools, I have learned that the voices of students and their parents, especially the voices of those most at risk, are often ignored. Educators must begin to create solutions by listening more and working with students and parents as equals.

The initial focus must be on decreasing truancy. Absenteeism is the most common indicator of overall student engagement and a significant predictor of dropping out. The Gates study showed that clear warning signs emerge from one to three years prior to the student dropping out. Some national studies show that warning signs can be seen as early as elementary school. Another study, a small one in Lowell with 146 students, found that only 32 percent of students who were absent more than 10 times in the fourth grade were performing at the appropriate grade level by 11th grade.[7]

As at-risk students, their parents, and educators collaborate to create solutions that will reduce the dropout rate, keeping students in school-each day, starting from their first day-is paramount. Teachers must discover why a student is not in school by communicating with parents. School administrators must hire teachers who are linguistically and ethnically compatible with students. School staff, community organizations, and government systems must provide needed services. Finally, teachers must be willing to question whether they might be contributing to problems and then take steps to change. It takes a village to ensure that children are engaged and on the road to discovering the benefits of learning.

Victoria Fahlberg, a PhD in clinical psychology, developed and implemented a truancy-prevention program for at-risk Asian, Hispanic, and Brazilian students and families in partnership with the Lowell Public Schools, increasing average attendance by 65 percent for more than 720 students since 2004 and parental involvement by over 50 percent. She is based in Lowell. Contact her at vfahlberg@comcast.net.

Endnotes

[1] "Left Behind in America: The Nation's Dropout Crisis" (white paper, Center for Labor Market Studies and Alternative Schools Network in Chicago, Northeastern University, Boston, 2009), http://hdl.handle.net/2047/d20000598.

[Back to story]

[2] A. Sum, I. Khatiwada, J. McLaughlin, S. Palma, "The Consequences of Dropping Out of High School" (white paper, Center for Labor Market Studies, Northeastern University, Boston, 2009).

[Back to story]

[3] According to A. Sum et al., about 7 percent of institutionalized young adults were living in long-term health-care facilities, while 93 percent were residing in adult correctional institutions and juvenile detention facilities.

[Back to story]

[4] J.M. Bridgeland, J.J. Dilulio Jr., and K.B. Morison, "The Silent Epidemic: Perspectives of High School Dropouts" (report, Civic Enterprises and Peter D. Hart Research Associates for the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, 2006), https://docs.gatesfoundation.org/Documents/TheSilentEpidemic3-06FINAL.pdf.

[Back to story]

[5] "Youth Voices: How High Schools Can Respond to the Needs of Students and Help Prevent Dropouts: Findings from Youth Focus Groups" (report, Massachusetts Department of Education, Boston, July 2007), http://www.doe.mass.edu/dropout/youthfocusgroup.pdf.

[Back to story]

[6] "Dropouts in Massachusetts Public Schools: District Survey Results" (report, Massachusetts Department of Education, Boston, April 2006), http://www.doe.mass.edu/news/news.aspx?id=2841.

[Back to story]

[7] "Attendance Patterns as a Predictor of Educational Attainment" (unpublished report prepared by the Mary Bacagalupo Forum Assessment Committee in Lowell, Massachusetts, 2007).

[Back to story]

Articles may be reprinted if Communities & Banking and the author are credited and the following disclaimer is used: "The views expressed are not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston or the Federal Reserve System. Information about organizations and upcoming events is strictly informational and not an endorsement."

About the Authors

About the Authors

Victoria Fahlberg

Resources

Resources

Related Content

Medication-assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder in Rhode Island: Who Gets Treatment, and Does Treatment Improve Health Outcomes?

Migration of Recent College Graduates: Evidence from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth

The Elm City Resident Card: New Haven Reaches Out to Immigrants

The Myth of the Irresponsible Investor: Analysis of Southern New England’s Small Multifamily Properties