Immigration to Manchester, New Hampshire

Immigration, historically important for Manchester's economy, today means a younger, more diverse population, with the attendant opportunities and challenges.

Immigration is an important source of U.S. population growth and demographic diversity.[1] Although much of the attention has focused on large metropolitan areas and border states such as Arizona and California, immigration has also affected smaller cities and rural areas nationwide.[2] In Manchester, New Hampshire, where immigration has been important for more than 100 years, the trend has greatly increased diversity.[3]

Historical Trends

In the 19th and 20th centuries, immigrants provided critical labor for Manchester's industrial economy and, until very recently, constituted a much larger proportion of the population than in the state or the nation overall. (See "Percent of Foreign-Born Population.")

In 1890, nearly one-half of Manchester's population was foreign born. That proportion declined because of increasingly restrictive national immigration policies and changing economics, particularly the closing of Amoskeag Mills in 1935.[4] But the immigrant share of the Manchester population remained higher than for the state. The proportion of immigrants nationwide surpassed that of Manchester only in the mid-1980s.

After waning for several decades, Manchester's foreign-born population started to increase in 1990, along with national trends. In fact, if it were not for immigration, the population of Manchester would have declined from 2000 to 2010. All of Manchester's growth (2.4 percent) can be attributed to immigration.[5] That increase might seem small, but any population growth is important for economic expansion.

What is new about immigration to Manchester is where workers come from. Amoskeag Mills was the largest textile-manufacturing company in the world at the turn of the 20th century, with workers who first came from New England farmlands, then in the 1850s and 1860s, from immigration. Irish immigrants were followed by Germans and Swedes. In the 1870s, Amoskeag Mills began heavy recruitment of French Canadians. In 1890, the proportion of foreign-born residents in Manchester's population peaked, largely driven by the mills' expansion. Immigration was, therefore, the source of both labor and Manchester's ethnic diversity in the ensuing decades.

Today countries of origin are changing, with 30 percent of immigrants still coming from Canada and Europe, but a greater percentage from elsewhere: Latin America (29 percent), Asia (26 percent), and Africa (15 percent).

In addition, since 1980, Manchester has been one of New Hampshire's refugee-resettlement sites, part of a program created by the Federal Refugee Act of 1980, which established sites in all states.[6] According to data from the New Hampshire Office of Minority Health, between 1980 and 2012, Manchester received almost 6,000 refugees. The average numbers of resettlements per year for the three most recent decades were, chronologically, 261, 252, and 257.[7]

Like the countries of origin for the overall immigrant population, those for the refugee population have shifted-away from European countries like Ireland, Germany, Sweden, and Greece and toward Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. The largest group to arrive in the 2010s is from Asia, and includes a substantial number of Bhutanese.[8] (See "The Bhutanese Community in Manchester.")

Aspects of Diversity

The growth of the immigrant population offers opportunities to Manchester.

Among immigrants, 67 percent are minorities; among the native born, only 11 percent are. Immigration is thus a driving force in increasing Manchester's diversity and cultural richness. Immigration also means Manchester is more youthful. Individuals tend to immigrate when they are younger, particularly when they are seeking better lives for themselves and their children or enough economic security to start a family. A younger age structure is correlated with economic growth. It can help replenish the labor force after retirements and is likely to increase the birth rate.

In 1980, Manchester had a median age of 31, compared with 30 for New Hampshire as a whole. Based on the most recent census data, the median age in the state went up to nearly 41, but Manchester's increased only to 36. Manchester's median age is substantially lower than the state's today and may continue to drop with more immigration.[9]

Although a growing immigrant population provides opportunities, disparities between foreign- and native-born populations can create challenges for social and economic integration. Manchester, like the rest of the country, encounters its primary challenges in the educational and language arenas. Successfully addressing such challenges can improve the economic well-being of all.

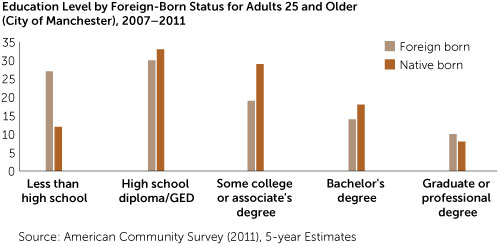

In Manchester, educational differences between the two populations are pronounced, particularly at the lowest and highest levels. (See "Education Level by Foreign-Born Status.") The proportion of the foreign born with less than a high school education (27 percent) is more than twice that of the native-born population (12 percent). Indeed, among Manchester's foreign-born population, less than a high school education is the second most common level of education attainment. A high school diploma or GED is the most common (30 percent). Although the majority of immigrants older than age 25 have at least a high school diploma, the educational disadvantage among this population creates more struggles for their financial well-being and economic mobility.

In contrast, a large percentage of immigrants have advanced degrees. In Manchester, 10 percent of the foreign-born population has a graduate or professional degree, compared with 8 percent of the native-born population. Given the recent growth in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics jobs, the foreign-born population with advanced degrees has an advantage in finding work.

As for language, Manchester has always been linguistically diverse. In the wider county, Hillsborough, there is a gap in English fluency between foreign- and native-born residents and also among different immigrant groups. Among foreign-born non-Hispanic whites, approximately 40 percent speak English "less than very well," compared with nearly 70 percent of foreign-born Hispanics, about 60 percent of foreign-born blacks, and 50 percent of foreign-born Asians. Historically, such disparities tend to narrow with each passing generation.[10] Additional policies enhancing language skills would likely ensure smoother transitions for immigrant families.

Implications

Manchester's immigrant population creates concrete opportunities for growth and vitality through its impact on the age structure of the city and the viability of the future workforce, its contribution to cultural diversity, and its additions to an otherwise declining population base.

The social and economic differences between the immigrant and native populations do create challenges, particularly in the short term, and the city must deal with the challenges in order to fully realize the opportunities. Investment in infrastructure, especially the city's schools, is critical for educating and integrating the immigrant population and would benefit all Manchester youth and the city as a whole. Support for the immigrant population, including its refugee component, is critical, and the work of nonprofit organizations such as Catholic Charities, the International Institute of New England, New American Africans, and the Bhutanese Community of New Hampshire shows that efforts to include immigrants in the life of a city can be successful.

Evidence on immigrant integration elsewhere in the country points to the importance of increasing the contacts between the foreign born and native born.[11] There is also strong evidence that the response of local leaders, citizens, and other stakeholders to the challenges can make a real difference.12 Responses that emphasize the problems often lead to divisiveness, whereas efforts that concentrate on inclusiveness and integration can leverage immigrant contributions.

As the center of business and industry in New Hampshire, Manchester has long offered immigrants a home. The benefits of continuing in this role depend on the city's success in welcoming, supporting, and educating its newcomers.

Sally Ward is professor emerita of sociology and a senior fellow at the University of New Hampshire's Carsey School of Public Policy, based in Durham. Contact her at sally.ward@unh.edu.

The Bhutanese Community in Manchester

by Caroline Ellis

Federal Reserve Bank of Boston

Last June, Sally Ward, Anthony Poore, and I met with Bhutanese Community Center members in Manchester, New Hampshire. They have a Nepali and Hindu background, unlike the dominant Bhutanese, who are Buddhist. Having been forced out of Bhutan, they lived in refugee camps in India for years. Each mentioned the exact day of arriving in the United States as if it were his birthday.

Krishna works at the International Institute of New England in Manchester and teaches adult education. He got a bachelor's in India and for 10 years taught in a private school outside the refugee camp. In 2009, Krishna, his wife, and son joined his parents and siblings in the United States. In 2010, he helped start Manchester's Bhutanese Community Center. He's happy he can afford a house because his son, who was 8 when he arrived and couldn't make noise in the apartment, now makes all the noise he wants.

Narapati is the center's operations director. He lived in India for 18 years. In the beginning, there was little food or health care. Forty children died on one horrible day. After the UN came, the camp improved. Narapati attended college in India for three years and is finishing his bachelor's here. In the refugee camp, he was a volunteer teacher. The teachers ran the camp, and the children were respectful. He has been making vocabulary lists, looking up English words on Google and practicing.

Narapati describes himself as being sandwiched between two generations. His parents aren't as independent as they once were. Language barriers make it hard for them to meet people. They attend English classes, and Narapati takes them to see interesting things "to give them hope." His children were born here and are fluent in English. The children have little understanding of Bhutanese traditions, so he must work to educate them. Narapati has never seen any hostility to the children. "They are American."

Rohit is studying health-information management in college. He helps the center's clients apply for health insurance. He was able to leave the refugee camp and get a bachelor's in physics in Nepal. From 8th grade on, he was a health volunteer in the camp, working on disease prevention, sanitation, and the like. His goal is to have a good job and, when he has kids, to be able to send them to the best colleges. He wants to give back to the country that has welcomed his community.

Tika serves as the center's acting director. At age 13, he was sent to a Catholic missionary school in India. His father, a political prisoner, was later forced to leave Bhutan on 72 hours' notice. Tika stayed with his parents in the camp on school vacations and worked in a preschool there. He went to college in India and got a job at Sun Life. He is working to understand American pronunciations and slang, creating a list of nicknames. (Jim for James and Bill for William can be confusing.) His goal is to be a "culture broker" for his community. The center has 12 full- and part-time staff around New Hampshire helping Bhutanese with transportation, interpretation, and more. Tika wants to help Bhutanese businesses learn the American system for getting loans.

"America has given us hope and new life and rescued us," says Tika. "We have 320 families here, and we have stable jobs. With a little investment in us, we could do so much for the country."

Endnotes

- This article is a synopsis of Sally Ward, Justin Young, and Curt Grimm, "Immigration to Manchester, New Hampshire: History, Trends, and Implications" (research brief, Carsey School of Public Policy, May 2014), https://scholars.unh.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1212,context=carsey.

- Daniel T. Lichter and Kenneth M. Johnson, "Immigrant Gateways and Hispanic Migration to New Destinations," International Migration Review 43, no. 3 (2009): 496−518; and Daniel T. Lichter, "Integration or Fragmentation? Racial Diversity and the American Future," Demography 50 (2013): 359−391.

- We refer to the Manchester metropolitan area because the focus is Manchester. Technically, the metropolitan area is the Manchester-Nashua metropolitan area.

- See Tamara K. Hareven and Randolph Langenbach, Amoskeag: Life and Work in an American Factory-City in New England (New York: Pantheon, 1978).

- In 2000, Manchester's population was 107,006. In 2010, it was 109,565, an increase of 2,559. The foreign-born population increased from 10,035 to 12,929. If not for that, the population would have decreased.

- Refugees have settled in 84 New Hampshire towns. Manchester, Concord, Laconia, and Nashua have had the largest number since the program began in 1980.

- The three most recent decades are 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s, and the numbers refer to the average numbers of resettlements per year for each decade. We used the annual average rather than the decade total because the 2010s are incomplete.

- Although 29 percent of Manchester's foreign-born residents in 2010 were from Latin America, none were refugees.

- According to American Community Survey five-year estimates, 2007−2011, New Hampshire has a median age of 40.7; Manchester's is 36.1.

- For an in-depth discussion of socioeconomic assimilation and the narrowing gap between the native and foreign born, see Richard Alba and Victor Nee, Remaking the American Mainstream: Assimilation and Contemporary Immigration (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2005).

- Michael Jones-Correa, "All Immigration Is Local: Receiving Communities and Their Role in Integration" (Washington, DC: Center for American Progress, 2011).

- Patrick J. Carr, Daniel T. Lichter, and Maria J. Kefalas, "Can Immigration Save Small-Town America? Hispanic Boomtowns and the Uneasy Path to Renewal," Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 641 (2012): 38-57.

Articles may be reprinted if Communities & Banking and the author are credited and the following disclaimer is used: "The views expressed are not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston or the Federal Reserve System. Information about organizations and upcoming events is strictly informational and not an endorsement."

About the Authors

About the Authors

Sally K. Ward, University of New Hampshire

Resources

Resources

Related Content

New England Study Group Past Meetings

Business Opportunities In Community Development Lending : Manchester

FedExchange 2011 New Hampshire

Racial and Socioeconomic Test-Score Gaps in New England Metropolitan Areas: State School Aid and Poverty Segregation