US Teens Want to Work

Weak economic growth and employer preferences have left teens with diminished opportunities to gain work experience and improve their chances of job market success.

After the Great Recession of 2007—2009 ended, several of the nation's key economic and labor-market indicators improved substantially. For example, since 2011, the number of payroll jobs in the United States has increased by more than 11 million, the unemployment rate has fallen to 5 percent from its peak of more than 9 percent in 2009—2010, and the real gross domestic product has grown by more than $1 trillion.

Yet despite signs of overall recovery, 16- to 19-year-olds still have extraordinary difficulty finding employment, whether part-time during the school year or full-time during summer.

Teens do want jobs. Moreover, exposing them to the world of work has broad benefits. The more a teen works today, the more she will work next year. Work also keeps teens off the streets, which may be particularly important for those from low-income families with fewer free-time options.

In the longer term, cumulative work experience during teen years has been shown to have a positive impact on employment and earnings of adults in their 20s. Work experience also helps teens develop desirable behavioral traits, like dependability and self-control—essential for virtually all occupations and often the sole qualifications for employment in entry-level jobs.

Declining Employment of Teens

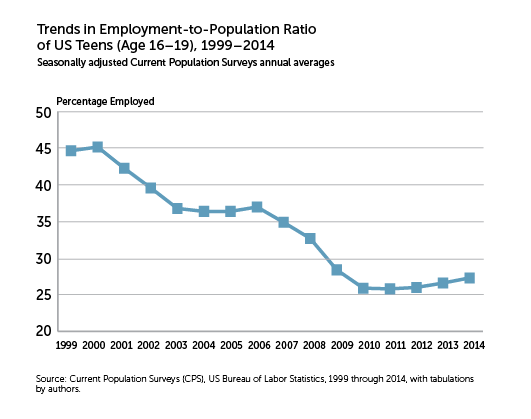

In a given month during 1999–2000, 45 percent of teens were gainfully employed. (See "Trends in Employment-to-Population Ratio of US Teens.") But the economic turbulence that has characterized the US economy since 2000 sparked a long and steep descent in employment prospects for teens. The dot.com recession, followed by the jobless recovery, saw a steady decline in the teen employment rate, falling to 37 percent by 2007. The Great Recession resulted in another sharp reduction in 2009.

By 2011, only one in four teens was employed in a given month during the year. In 2014, just slightly more than 27 percent of US teens were employed, a modest increase of just 1.8 percentage points.

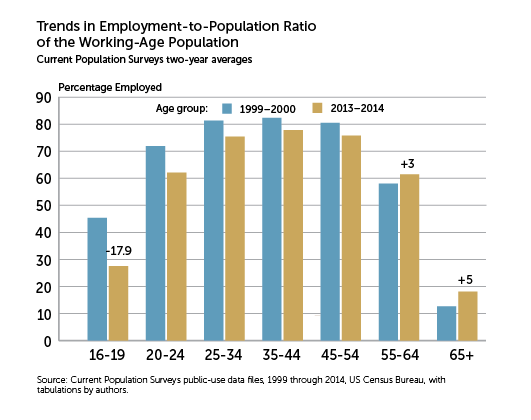

A comparison of the trend in the employment-to-population ratio by age reveals that teens experienced the sharpest decline (-18 percentage points), followed by young adults (aged 20–24), among whom the ratio declined by nearly 10 percentage points. Workers in different age groups between 25 years and 54 years experienced declines of 4 to 6 percentage points. In contrast, the employment-to-population ratio of older workers (55 and over) increased by 3 to 5 percentage points between 1999–2000 and 2013–2014. (See "Trends in Employment-to-Population Ratio of the Working-Age Population.")

This age twist in employment rates is historically a unique occurrence and stands in sharp contrast to the conventional wisdom of an aging population causing the decline in the nation's overall employment rate.

Declining Employment in Summer Months

In the summer months, when schools are closed, teens often aspire to work. Historically, US teens worked at substantially higher rates during the summer months. Research has found that teens who remain idle in summer are more likely than their employed counterparts to risk social isolation and to get involved in antisocial or even criminal behaviors.[1]

Sadly, the share of teens likely to work during the summer months has declined sharply. More than half of teens were employed during the summer months of 1999 and 2000. By summer 2007, the employment-to-population ratios of teens had plummeted to 39.6 percent. (See "Summer Trends in Employment-to-Population Ratios of US Teens.") During and after the Great Recession, employment prospects for teens fell even further, reaching historic lows of 26.9 percent during the summer months of 2010–2011. Even as the nation's economy has recovered, the teen summer employment rate has barely budged. During the summers of 2013 and 2014, only 31 percent of teens were employed.

In absolute terms, roughly 8.3 million teens were employed during the summer months of 1999–2000. By 2013—2014, only 5.3 million teens were employed, a drop of 36 percent in absolute employment level.

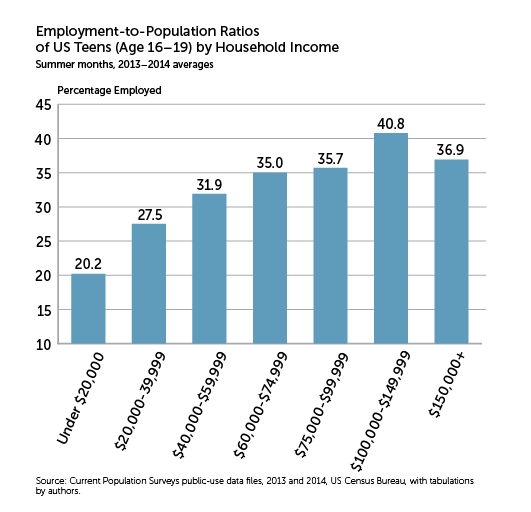

Since 2000, the pace of loss in summer employment has varied by gender, race/ethnicity, and age subgroups, with a greater decline occurring among males, Asians, blacks, and 16- to 17-year-olds.[2] The summer employment rates of teens have also varied widely by their family income. (See "Employment-to-Population Ratios of US Teens (Age 16–19) by Household Income.")

Teens from affluent families were more likely to be employed than teens from low-income families. Only 1 in 5 teens from low-income families (less than $20,000 annual income) were employed in the summer months of 2013–2014. Teen employment rates rose fairly steadily with levels of family income, rising from 27.5 percent among teens in families with annual incomes between $20,000 and $39,000, to 32 percent among teens in families with annual incomes between $40,000 and $59,000, and 41 percent among teens with annual family incomes between $100,000 and $149,000.

Compared with teens from low-income families (family income under $20,000), teens from affluent families (family income $100,000 and over) were nearly twice as likely to be employed during summer months of 2013–2014.

What Do Teens Want?

There has been debate about whether teens want to work in summer or have part-time jobs during the school year. Some research shows that teens are opting more often for school-related activities than for work in summer months.[3] But although school enrollment levels during the summer months have increased by more than 10 percentage points since 2000, the lack of work among teens does not appear to stem from a lower desire to work.

Rather, we see that many teens want to work. Evidence shows a high incidence of underutilization among teens–measured by unemployment, hidden unemployment, and underemployment. In the summer of 2013–2014, 1.55 million teens were unemployed (the open unemployed), 1.08 million wanted to work but had given up looking for work (the hidden unemployed), and another 0.6 million had a desire to work full-time, but were working part-time for economic reasons (the underemployed). (See "Trends in Labor Market Problems of Teens.")

The combined collections of these three groups of teens, which we have labeled as the underutilized, was 3.23 million, representing an underutilization rate of 40.7 percent, the highest among any group of workers and much higher than the teen underutilization rate of 26.4 percent in the summer months of 1999–2000.

Our findings reveal that teens do have a strong desire to work in summer months but that their ability to find work has deteriorated sharply since the full-employment days of the late 1990s.

Paul Harrington is professor and director at Drexel University's Center for Labor Markets and Policy in Philadelphia, where Ishwar Khatiwada is an economist. Contact them at peh32@drexel.edu and ik329@drexel.edu.

Endnotes

- See Andrew Sum, Mykhaylo Trubskyy, and Walter McHugh, "The Summer Employment Experiences and the Personal/Social Behaviors of Youth Violence Prevention Employment Program Participants and Those of a Comparison Group" (report, Center for Labor Market Studies, Northeastern University, prepared for Youth Violence Prevention Funder Learning Collaborative, Boston, July 2013), http://www.northeastern.edu/clms/wp-content/uploads/CLMS-Research-Paper2.pdf.

- See Neeta Fogg, Paul Harrington, and Ishwar Khatiwada, "The Summer Jobs Outlook for Teens in the US" (white paper, Center for Labor Markets and Policy, Drexel University, May 2015), http://www.asnchicago.org/docs/SummerJobsOutlook4TeensUS_DrexelReport5-8-15.pdf.

- See Jeff Clabaugh, "Why Teens Don’t Want Summer Jobs," Washington Business Journal, April 21, 2015.

Articles may be reprinted if Communities & Banking and the author are credited and the following disclaimer is used: "The views expressed are not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston or the Federal Reserve System. Information about organizations and upcoming events is strictly informational and not an endorsement."

About the Authors

About the Authors

Paul Harrington, Drexel University

Ishwar Khatiwada, Center for Labor Market Studies