Modern Land Banking: Can It Work in Southern New England?

With new forms of land banking documenting success outside the Northeast, the applicability of the approach to New England is worthy of consideration.

For about four decades, U.S. regions have employed land banks to address uneven urban development. Historically, land banks had numerous goals and limited powers. Today, although some regions have adapted their land banks to be more reflective of contemporary property markets, New England has been less inclined to do so.[1]

Why Modernize?

Increased foreclosures, lower home prices, and a proliferation of low-value and no-value homes have led to renewed interest in land banks and their ability to handle such properties.

Frank Alexander offers a framework for understanding modern public land banks. Like actual banks, they 1) store assets, 2) hold capital reserves, 3) operate within a regulatory framework, and 4) may create secondary markets.[2] Compared with traditional land banks, they focus on acquiring and disposing of distressed properties. [3] They also pursue a broad public mission and have the flexibility to operate as independent private entities. They may acquire properties through tax foreclosure, mortgage foreclosure, market transfers, or donations. They do not hold land indefinitely but aim to impact housing markets through strategic disposition.[4]

Current interest in modern land banks is largely due to the visibility of several successes during the Great Recession. The Genesee County Land Bank Authority (GCLBA), encompassing Flint, Michigan, became a model for other communities seeking to set up land banks in response to the mortgage crisis.[5]

In the county seat of Cleveland, Ohio, the Cuyahoga County Land Reutilization Corporation (CCLRC) acquired 495 properties in roughly one year, demolished 167, and transferred 80 to cities or redevelopers. The nonprofit CCLRC has unusual public powers and reliable funding from interest and penalties on delinquent property taxes and assessments.

Benefits and Challenges

Federal Reserve Board researchers recently suggested the use of land banks as an option for low-value properties.[6]

However, only about 10 states have passed enabling legislation. And according to the Federal Reserve Board's analysis, only about half of the Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Federal Housing Administration (government-sponsored entities, or GSEs) inventory of bank-owned foreclosed properties with a value of $20,000 or less is in a metropolitan area with an existing land bank.

The Federal Reserve authors suggest governments at the federal, state, or local level could consider increasing funding and technical assistance to existing land banks, encourage the creation of more on the local or regional level, or create a national program.

But governments that pursue land banking should recognize certain challenges. Cleveland's land bank has struggled to capitalize projects. It also has found that many community development groups have limited capacity to successfully rehabilitate the parcels they acquire and are burdened by time-consuming administrative procedures. In Genesee County, the land bank has had trouble finding qualified buyers for rehabbed homes.

Southern New England

Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island operate under different land bank legislation and have differing needs. Rhode Island ranks high nationwide in terms of foreclosure rates at 14th, whereas Massachusetts is 30th and Connecticut is 38th.[7]

Massachusetts lacks state enabling legislation but has hundreds of low-value GSE-owned properties that could benefit from a land bank.[8] Nevertheless, with property values higher than the national average, the state is not experiencing acute pressure. And although some areas were hit hard by foreclosure and falling prices, the median single-family home price in Massachusetts as of December 2012 was $300,000, significantly higher than the national average of $180,300. The foreclosure rate also is lower than the nation's.[9]

Connecticut

Connecticut has land bank enabling legislation that is not currently funded. Instead, initiatives tend to work off other state statutes.

Connecticut's land bank program operated roughly 1990 to 2000. Too narrowly defined to function as a modern land bank (participation was limited to nonprofit corporations funded by state bonding), it was successful for some communities, providing housing for 250 families in the Hartford region.

Certain Connecticut towns create quasi land banks by entering into development agreements that include the sale of tax liens at a deep discount.[10] Both Plainfield and Norwich use that approach, giving developers the right to foreclose on brownfields.

Elsewhere, the Department of Revenue Services, through the Neighborhood Assistance Act, helps local development corporations use tax credits to purchase homes out of foreclosure.

Rhode Island

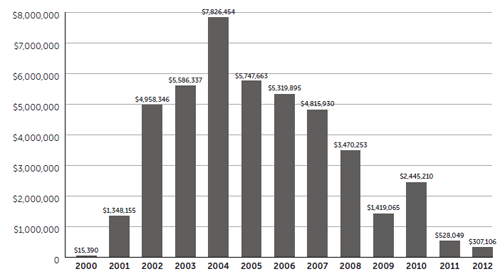

Rhode Island's legislatively enabled land bank became active in 2001. Rhode Island Housing, which developed its land bank to promote the production of affordable housing, is authorized to acquire properties on behalf of nonprofit developers and municipalities and hold them until the applicants obtain development funds. (See "Rhode Island Housing Annual Investments in Land Bank Program." )

Rhode Island Housing Annual Investments in Land Bank Program

The land bank limits the program to eligible developers, including government entities, public housing authorities or redevelopment agencies, nonprofit corporations and partnerships, or joint ventures of eligible developers. Among its threshold requirements: producing long-term affordable homes.

In Rhode Island, land banking has helped participating organizations assemble a critical mass of properties for large-scale redevelopment or revitalization. It also has enabled nonprofits that are waiting for federal revitalization funds to compete with speculators. However, the unstable real estate market requires that administrators carefully evaluate each proposal's viability. Thus, in addition to applying the usual funding standards, they also evaluate neighborhood trends, with an eye toward sustainable development.

Should We Modernize?

It is not entirely clear that the modern land bank is appropriate for New England. Several questions come to mind. Do modern land banks mean to both forecast and influence property markets? Real estate prices are not easily forecast. Rhode Island Housing acquired land during the expansion of the real estate bubble under the assumption that prices would continue to rise, but they fell, and the land bank now holds property worth less than the purchase price.

How accurate can land bank staff be about determining future market conditions? Although they are allowed to operate at a loss, they are generally limited to a holding period of 10 years. Can they respond to market conditions under that time constraint?

Holding costs are less difficult to forecast. By acquiring real property, land banks assume the responsibility of maintaining it. What is the impact of land bank properties on neighboring privately owned properties? What level of maintenance is necessary to avoid a negative impact?

Modern land banks aspire to increase local property demand and improve prices by reducing supply. But most process fewer than 100 properties a month. If they withhold inventory, will they really have much influence on the market?

Property markets change, and land banks must change to endure. The Rhode Island land bank has kept introducing new program elements and pursued different sources of funding. However, more narrowly defined programs may be difficult to sustain, as in Connecticut. Massachusetts as a whole may not need a land bank, but some pockets would benefit.

Given that a goal of the modern land bank is to improve housing prices in depressed areas, it may not fit New England, where housing demand remains relatively high. Nevertheless, the land bank successes achieved elsewhere suggest that the model deserves consideration.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Annette Bourne of Rhode Island Housing and Timothy Bates of Robinson , Cole, LLC, for their descriptions of programs in Rhode Island and Connecticut.

Erin Graves is a policy analyst in the Regional & Community Outreach department of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. Contact her at erin.m.graves@bos.frb.org.

Endnotes

[1] Erin Graves, "Modern Land Banks in New England" (Regional , Community Outreach issue brief, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston), forthcoming. [Back to story]

[2] Frank S. Alexander, Land Banking as Metropolitan Policy (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 2008). [Back to story]

[3] Thomas James Fitzpatrick, "How Modern Land Banking Can Be Used to Solve REO Acquisition Problems (Social Science Research working paper series, May 3, 2010), http://ssrn.com/abstract=1830496. [Back to story]

[4] Adding to the confusion, many entities called "land banks" in fact function as land trusts. [Back to story]

[5] Laura Schwarz, "Neighborhood Stabilization Program: Land Banking and Rental Housing as Opportunities for Innovation," Journal of Affordable Housing and Community Development 19, no. 1 (2009): 51-79. [Back to story]

[6] The U.S. Housing Market: Current Conditions and Policy Considerations (Washington, DC: Board of Governers of the Federal Reserve System, 2012). [Back to story]

[7] See RealtyTrac, "National Real Estate Trends, 2011," http://usliberals.about.com/od/Election2012Factors/a/Foreclosure-Rates-By-State.htm. [Back to story]

[8] The Massachusetts Land Bank oversaw the disposition of former military land. Cape Cod, Martha's Vineyard, and Nantucket have public land banks that function as preservation land trusts. [Back to story]

[9] "2012 Mass. Home Sales Highest in Six Years" (press release, Warren Group, Boston, January 2013); and National Association of Home Builders, "New and Existing Single Family Home Prices, U.S.," http://www.nahb.org/fileUpload_details.aspx?contentID=55764. [Back to story]

[10] A tax lien is a legal claim against real property for unpaid property taxes or other property charges. In a tax lien sale, the city sells delinquent tax liens to a single authorized buyer. The lien holder purchases the right to collect the money that is owed to the city. Ultimately, if the property owner does not pay what is owed, the lien holder can begin a formal foreclosure proceeding. [Back to story]

Articles may be reprinted if Communities & Banking and the author are credited and the following disclaimer is used: "The views expressed are not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston or the Federal Reserve System. Information about organizations and upcoming events is strictly informational and not an endorsement."

collapse all

collapse all

expand all

expand all