Multiage Education

As educators seek ways to improve scholastic outcomes, they might consider classrooms comprising two age groups. Done right, multiage education promotes more-individualized learning and better student cooperation.

Educators are constantly looking for new ways to improve outcomes for children, especially children in troubled schools and neighborhoods. One idea worth considering is multiage education, currently being employed in several Boston suburbs.

Despite initiatives like the Massachusetts Education Reform Act (MERA) of 1993-which helped to reduce achievement gaps among school districts by increasing relative spending in districts that serve large shares of disadvantaged students-sharp educational disparities persist.[1] Multiage education, which can be used to energize learning, represents an approach that may help to alleviate such disparities.

What exactly is multiage education?[2] As used today, the term describes primary or elementary classrooms that blend two- to three-year age groups. A look at programs currently under way may provide a better understanding of this alternative to age-based classrooms and show how its characteristically child-centered curricula can improve student engagement.

Setting One's Own Pace

Conversations with principals and teachers at a variety of Massachusetts public schools highlight a diversity of approaches to administering multiage programs. At one end of the spectrum are schools offering one or two multiage classes. At the other extreme are schools fully entrenched in the multiage philosophy and offering blended classrooms only.

The length of time that the programs have existed also varies, with some around for decades and others in their infancy, celebrating only their second or third year.

Regardless of how long programs have been around, their approach to structuring lessons is similar. They generally start with a group lecture to introduce new concepts, followed by individual lesson plans and extensive work in small teams. Students move to the next curriculum level only when ready. All programs emphasize the importance of letting children set their own pace. They get gently pushed by teachers when needed, but they are expected to do their best and to challenge themselves.

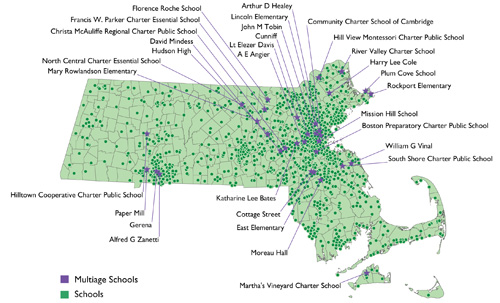

Location of Schools with Multiage Education Programs

In interviews, teachers noted several positive outcomes of multiage classrooms. Many saw an efficiency gain from having only one-third to one-half of their class replaced each year. Such low turnover, they claimed, enabled them to give meaningful assignments from day one, rather than spending the first six weeks assessing students' strengths, weaknesses, and learning styles. The structure also facilitated the task of getting to know the new students any given year.

Additionally, returning students already knew the rules, so they could model what was expected in the classroom, laying the foundation for the mentor/mentee relationships that naturally extend across both social behavior and academic work in multiage classrooms. Teachers also noted that multiage classes sometimes offer new opportunities for students to become leaders.

As one teacher remarked, "The second- year students know how things are run in the classroom, so even shy, quiet children who normally wouldn't get a chance to fill a leadership role often do in a multiage environment."

The fostering of mentor/mentee relationships that can create a sense of community and confidence was frequently mentioned. According to one teacher, "There is a camaraderie that is not seen in the traditional classrooms due to the relationships made between the kids."

Several teachers speculated that people entering a multiage classroom pick up on the sense of community coming from the way students work in small groups (often around tables or on the floor) and the way they interact as they help one another with assignments.

Several teachers also described a hard-to-measure but tangible self-confidence in children, likely stemming from a sense of community in their classrooms, their engagement in their studies, and the way the approach gives them control over their learning. With curriculum centered on the individual needs of students, children get a say in how much time they spend on practicing concepts before moving on to other lessons. That not only allows them to absorb topics at their own pace, but also helps them shape their learning path.

It is true that many of the teaching strategies discussed here could perhaps improve instruction in traditional age-based classrooms as well, but for multiage education such strategies lie at the heart of the approach. They help sustain child-centered principles while encouraging engagement and motivation. Children are involved in making the educational decisions.

One teacher commented that it was not uncommon in a multiage classroom to hear a child say, "I can't talk right now because I need to get my work done." Another suggested that anyone entering such a classroom would be hard pressed to tell which students were older or younger, since everyone works so nicely together.

Challenges

Multiage education does pose some challenges. Teachers commented on how complicated it was to keep track of individualized curricula in multiage environments. Although the programs teach students how to navigate independently through learning materials and to take an active role in their education, most small-group work requires that teachers identify children with compatible skill levels.

Teachers overseeing the work accomplished in their classes also have to be ready to guide children to new groups and activities when appropriate. It is the teacher's responsibility to make sure the students stay engaged. Moreover, teachers of blended classes have to keep track of which books were read in the first year, so that when students return for their second year, they tackle new challenges. Lesson plans must therefore span two years instead of one.

Interviewed teachers also mentioned how important it is that schools launch multiage models for the right reasons, observing that programs started for budgetary reasons do not work. They warned that successful multiage programs take considerable planning and effort, and they speculated that new teachers thrown in without individual commitment or sufficient training might feel overwhelmed.

Interviewees also noted that misunderstandings about multiage objectives can create tension in schools that have both multiage and age-based classes, because some people believe, incorrectly, that multiage classrooms skim off the brightest students. On the contrary, principals and teachers emphasize the importance of having heterogeneous classrooms to allow for greater individual achievements. A lot of effort is spent making sure multiage classes are balanced. Still, teachers noted that it can be challenging to teach in multiage environments when outsiders do not clearly understand the goals.

Identifying another challenge, some teachers commented that testing for the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System (MCAS) made the multiage environment more difficult. Other interviewees, however, had not found that to be the case. One teacher commented that students did not fare very well on fifth grade MCAS tests if they had been taught fifth grade material in the prior year.[3] He articulated a dilemma that teachers faced: "Do you spend additional time cramming for the test or let them do poorly? Neither answer seems like a good way to go."

That teacher's suggestion is to institute "cluster" exams, with students responsible for materials taught in several primary years, or intermediate years, or upper years. It would be one way, he thought, to fit testing with the multiage concept. Another teacher said that although she and her co-workers were worried when the MCAS requirements were first established, after seeing the questions, they decided it was reasonable to expect well-educated children to be able to answer them. As a result, they did not make any changes to their school's curriculum, and their students did do well on the exams.

Overall, the majority view was that teaching in multiage classrooms can be hard work but worth the effort. Teachers and principals perceived that students in multiage classrooms tend to do at least as well as, if not better than, students in traditional aged-based classrooms. That seems to be especially true when student outcomes are evaluated by more than test scores and include such measures as fewer behavioral issues at school, lower rates of in-school suspensions or truancy, and higher attendance rates.[4] Several principals also said that it was important to be able to offer students and parents more choice in learning models, given that one size does not fit all.

Delia Sawhney is a director of the Economic Research Information Center at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

Endnotes

[1] Thomas Downes, Jeffrey Zabel, and Dana Ansei, "Incomplete Grade: Massachusetts Education Reform at 15" (white paper, MassINC, Boston, May 2009).

[2] Ruiting Song, Terry E. Spradlin, and Jonathan A. Plucker, "The Advantages and Disadvantages of Multiage Classrooms in the Era of NCLB Accountability," Education Policy Brief, no. 1 (winter 2009): 5.

[3] Teachers in a blended fourth and fifth grade class alternate material each year, so some students may learn traditional fifth grade material before they learn traditional fourth grade material.

[4] An exploratory probe of the MCAS results showed students at the multiage schools generally holding their own. Other indicators suggest students are more engaged in school and have fewer behavior issues. See Delia Sawhney, "Multiage Education in Massachusetts: Program Details and Student Outcomes" (white paper, Harvard Library, Cambridge, Massachusetts, March 2012).

Articles may be reprinted if Communities & Banking and the author are credited and the following disclaimer is used: "The views expressed are not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston or the Federal Reserve System. Information about organizations and upcoming events is strictly informational and not an endorsement."

About the Authors

About the Authors

Delia Sawhney, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston