The Effective Use of Property Tax Incentives for Economic Development

After the Great Recession, many local governments now have two major goals: to spur economic growth to address high unemployment and stagnant or declining incomes, and to protect their tax base in the wake of cuts in state aid to local governments and the collapse of the housing market.[1] In hopes of attracting new manufacturing plants, corporate headquarters, or research and development centers, many localities have offered property-tax incentives. But are local governments giving away more of their tax base than can be justified by the economic benefits received?

A recent New York Times series estimated that state and local governments nationwide forgo more than $80 billion of tax revenue annually as a result of business incentives.[2] Our own research concludes that local property-tax incentives alone total at least $5 billion to $10 billion per year.[3] One New England example illustrates how costly such programs can be. In Connecticut for fiscal year 2009, property tax exemptions for machinery and equipment reduced potential local revenues by $57.3 million while enterprise-zone property-tax abatements cost the state and its local governments $14.5 million.[4] The combined cost of these two incentives could have paid the salaries for more than 1,000 Connecticut teachers.[5]

Every state allows the use of property-tax incentives for business. Within New England, every state but New Hampshire has a stand-alone property tax abatement program, every state but Vermont has enterprise zones, and all six states allow tax-increment financing.[6] Ineffective incentives reward companies that would have chosen the same location without tax breaks, while increasing taxes for homeowners and reducing spending on police, education, and other vital public services. Given the need to spur economic growth without compromising localities' fiscal health, policymakers should consider strategies to improve the effectiveness of property- tax incentives for economic development. Our research suggests five approaches.

Do Not Approve All Requests

When evaluating property tax incentives, perhaps the most important question is whether they actually make a difference. Do tax breaks cause a business to choose a site it would have passed up without incentives, or would it have chosen the same location regardless?

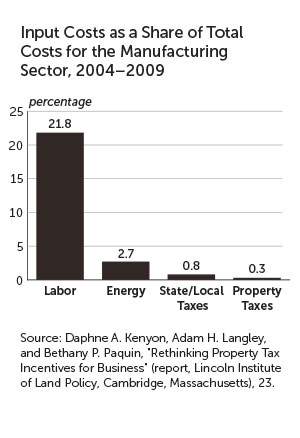

Businesses consider many factors during the site-selection process, including labor costs and skills of the local workforce, proximity to suppliers and customers, access to transportation (highways, ports, and railroads), energy costs, the cost for office or industrial space, regulations, and state and local taxes. The likelihood that property taxes will tip an organization's location decision depends on the taxes' share of business costs relative to those other factors, and how much property taxes vary across other potential sites compared with those factors. The average manufacturing plant, for example, spends nearly 75 times more on labor than on property taxes. (See "Input Costs as a Share of Total Costs." ) In many cases, small differences in labor costs could offset huge property-tax incentives.

Furthermore, businesses have a clear motivation to exaggerate the importance of tax incentives since they are unlikely to receive tax breaks unless policymakers believe the incentives will sway their location decision. In some cases, businesses negotiate for tax incentives after they have already chosen a location.[7] Sepracor, a pharmaceutical company that already had one building in Marlborough, Massachusetts, applied for a property-tax exemption in 2007 for a second building and began construction that same year. The city council didn't approve the tax break for the expansion until the next year.[8]

Although policymakers rarely have enough information to judge the impact of tax-incentive packages accurately, they can take two measures to avoid overusing them. First, they can be cautious in approving tax-incentive packages and refuse to act as rubber stamps for business requests. This advice may resonate more clearly with New England policymakers after the high-profile collapse of baseball player Curt Schilling's video-game company, 38 Studios, which left the state of Rhode Island on the hook for at least $75 million. Rhode Island lured the company from Massachusetts with an incentive package that Commonwealth officials declined to match.[9]

There are ways to take into account the possibility that tax incentives may not make a difference.[10] For example, a 2010 Connecticut study considered a range of probabilities that incentives affect company behavior. The report calculated whether tax incentives were cost-effective assuming that 20 percent, 50 percent, or 100 percent of business investment was caused by the incentives. It is not acceptable to assume that all economic growth associated with a new facility is the result of tax incentives.

Take a Targeted Approach

Research has found that when the use of tax incentives within a region grows, their effectiveness wanes.[11] If just a few municipalities offer tax breaks, then the incentives may help attract investment to those communities. But if incentives are widely available, businesses will be able to find similar offers in many communities, and the tax breaks will largely offset one another. Maine is one of three states in which enterprise zones, initially designed to target benefits to specific geographic areas, have expanded over time.[12] Maine expanded its Pine Tree Development Zone program in 2009 to make the entire state eligible.

Avoid Incentive Wars

Another concern is that if neighboring cities and towns use property-tax incentives to compete for a new facility, they could leave their metropolitan area as a whole worse off. Localities may view it as in their self-interest to beat out neighbors for new business investment, but this competition is often a zero-sum game, with municipalities using incentives to move jobs around rather than create new ones. If widespread use of tax incentives significantly reduces the region's tax base, then this competition can actually be worse than a zerosum game-increasing taxes on homeowners and businesses that have not benefited from incentives or reducing funds for schools, public services, or programs that could more effectively spur economic development.

Because of New England's high concentration of local governments, the region may be particularly vulnerable to destructive competition between localities. Policymakers should take care to avoid the business-poaching practices that have made the Kansas City metro area infamous for cross-border tax-incentive wars. Applebee's, for example, relocated its headquarters three times within a 20-mile radius between 1993 and 2011, twice crossing the state border, each time taking advantage of state and local economic development incentives.[13]

Don't Compete, Cooperate

Instead of competing, municipalities would be wise to collaborate to spur economic development. The fates of communities in a metro area are often intertwined because the economic benefits of a new company accrue to the entire area, not just to the individual jurisdiction that hosts it, as the firm hires workers from throughout the region and contracts with businesses from neighboring cities.

The Metro Denver Economic Development Corporation offers perhaps the nation's best example of a collaborative approach to regional economic development. The group's 70 cities, counties, and economic development organizations adopted a code of ethics in the mid-1980s that established principles all members are expected to follow. The pact does not rule out tax incentives or site competition among its members, but it focuses on reducing those practices most likely to lead to destructive incentive wars. The goal is to promote "Metro Denver First" and individual communities second.

Evaluate Effectiveness

It is also important to evaluate the effectiveness of business-tax incentives. A recent study by the Pew Center on the States reviewed hundreds of documents to determine whether states evaluate major tax incentives, measure their economic impact, draw clear conclusions, and use evaluations to inform policy choices. The report found that Connecticut was one of 13 states leading the way in evaluating state tax incentives, but that three other New England states (Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont) were among the 16 states that did not publish a single document between 2007 and 2011 evaluating the effectiveness of any tax incentive.[14]

Massachusetts is looking at the effectiveness of tax incentives as part of a broader review of tax expenditures. A 2012 report by the Massachusetts Tax Expenditure Commission concluded that the state has a high share of tax expenditures compared with other states and lacks reporting and evaluation. The commission recommended that several major tax expenditures, including the Economic Development Incentive Program, sunset every five years to ensure that ineffective programs do not continue indefinitely, and it proposed that others be reviewed every five or 10 years.[15]

Without careful use of this economic development tool, costly and ineffective tax-incentive programs can drain precious state and local resources without substantially boosting economic development.

Daphne A. Kenyon is a visiting fellow at the Lincoln Institute for Land Policy in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where Adam H. Langley is a research analyst and Bethany P. Paquin is a research assistant. Contact them at dkenyon@lincolninst.edu or alangley@lincolninst.edu.

Endnotes

[1] Thanks to Stan McMillen and Joan Youngman for their helpful comments. [Back to story]

[2] Louise Story, "As Companies Seek Tax Deals, Governments Pay High Price," New York Times, December 1, 2012. One analyst argues the numbers are inflated by wrongly counting some general features of tax policy as incentives, such as sales tax exemptions for business inputs: David Brunori, "The New York Times Gets It Wrong," State Tax Today, December 17, 2012.[Back to story]

[3] Daphne A. Kenyon, Adam H. Langley, and Bethany P. Paquin, "Rethinking Property Tax Incentives for Business" (Policy Focus Report, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2012), http://www.lincolninst.edu/pubs/2024_Rethinking-Property-Tax-Incentives-for-Business [Back to story]

[4] "An Assessment of Connecticut's Tax Credit and Abatement Programs" (report, Connecticut Department of Economic and Community Development, December 2010), http://www.ct.gov/ecd/lib/ecd/decd_sb_501_sec_27_report_12-30-2010_final.pdf. [Back to story]

[5] See Digest of Education Statistics (Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, 2011), http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2012001. [Back to story]

[6] Details on these programs come from various state sources and "Significant Features of the Property Tax," http://www.lincolninst.edu/subcenters/significant-features-property-tax/. [Back to story]

[7] Peter Fisher, "The Fiscal Consequences of Competition for Capital," in Reining in the Competition for Capital, ed. Ann Marusen (Kalamazoo, Michigan: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 2007), 65. [Back to story]

[8] Paul Crocetti, "Marlborough Finance Board Wrestles Over Sepracor Tax Break," MetroWest Daily News, October 21, 2008. [Back to story]

[9] Hiawatha Bray, "R.I. Races to Save Curt Schilling's Company," Boston Globe, May 16, 2012, http://www.bostonglobe.com/business/2012/05/15/races-save-curt-schilling-company/66q7c5GCrPGQYz8eeWT8jL/story.html . [Back to story]

[10] "Evidence Counts: Evaluating State Tax Incentives for Jobs and Growth" (report, Pew Center on the States, Washington, DC, 2012), 35. [Back to story]

[11] John E. Anderson and Robert W. Wassmer, Bidding for Business: The Efficacy of Local Economic Development Incentives in a Metropolitan Area (Kalamazoo, Michigan: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 2000). [Back to story]

[12] The other two are Arkansas and Kansas. [Back to story]

[13] Kevin Collison, "Applebee's to Move Headquarters, 390 Jobs to Kansas City, Mo., from Lenexa," Wichita Eagle, May 28, 2011. [Back to story]

[14] Note that Vermont's main business-incentive program, the Vermont Employment Growth Incentive program, is regularly evaluated but was not included in the Pew study since it mainly offers cash incentives rather than tax incentives. [Back to story]

[15] Commonwealth of Massachusetts, "Report of the Tax Expenditure Commission," April 30, 2012, http://www.mass.gov/dor/docs/dor/stats/taxexpenditure- commission-materials/final-report/tec-report-with-appendicesnew.pdf. [Back to story]

Articles may be reprinted if Communities & Banking and the author are credited and the following disclaimer is used: "The views expressed are not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston or the Federal Reserve System. Information about organizations and upcoming events is strictly informational and not an endorsement."

About the Authors

About the Authors

Daphne A. Kenyon, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy

Adam H. Langley, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy

Bethany P. Paquin, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy