Levels and Trends in the Income Mobility of U.S. Families, 1977–2012

Much of America’s promise is predicated on the existence of economic mobility—the idea that people are not limited or defined by their current economic circumstances, but can move up the income ladder based on their effort and accomplishments. Changes in economic mobility are of particular consequence when economic disparity among families is increasing, as in the United States in recent decades. When family income inequality is increasing, changes in the degree to which families move up and down can either offset or amplify longer-term inequality. Other things being equal, an economy with rising mobility will result in a more equal distribution of lifetime incomes than an economy with declining mobility.

This paper examines patterns of income mobility of U.S. families with working-age heads and spouses between 1977 and 2012, using data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) and a number of mobility concepts and measures. Calculating these measures for overlapping decades, the paper documents mobility levels and trends based on a post-tax-and-transfer measure of family income adjusted for family size.

Key Findings

Key Findings

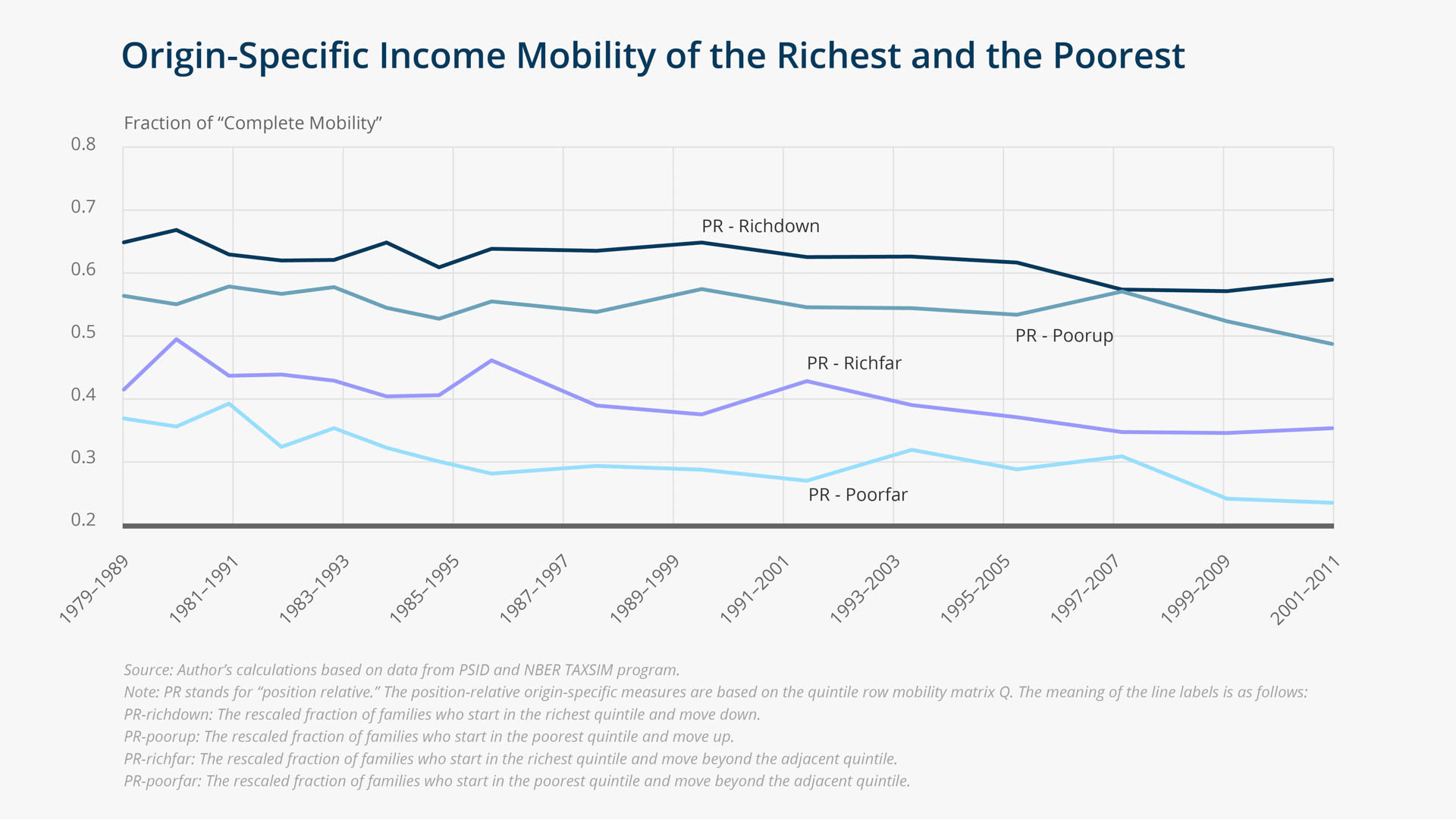

- Considering mobility only in terms of movement out of an origin income group (a quintile for example), 10-year mobility between 1977 and 2012 was 70 to 80 percent of what would be expected if the end-of-period income group had been independent of the starting group. When accounting for the distance of moves or changes in detailed rank, mobility in these decades was even more limited compared to the same “independent-of-starting-point” standard—as low as one-quarter as great.

- By and large, different mobility measures yield similar pictures of mobility time trends over the 1977–2012 interval. Most mobility measures indicate that family income mobility was lower in the more recent decades than in earlier decades. Upward mobility for those starting in the poorest quintile declined especially markedly over the last two decades studied (1999–2009, 2001–2011), both of which included portions of the Great Recession.

- The distribution of long-term income (family income averaged over 10 years) has been much more unequal in recent decades than in the 1980s. The trend has been visibly steep, regardless of the measure of inequality or income employed. Thus, mobility has been insufficient to offset the considerable rise in short-term (cross-sectional) inequality.

Exhibits

Exhibits

Implications

Implications

Neither worker protections (for example, minimum wage, union support), education policy, nor tax and transfer policies in the United States have produced increases in family income mobility from the 1980s to the present, in some cases because those policies have shifted in disequalizing directions. Beyond overall patterns, the data indicate that the typical family in the poorest one-fifth of the family income distribution is less likely to move up beyond that group’s real-dollar ceiling within a decade or move up to or beyond the middle quintile than a family in the poorest one-fifth was 20 years earlier, with the Great Recession apparently a factor in this marked deterioration of prospects. These facts suggest that policy remedies for those at the bottom should aim beyond short-term help, as those who are poor at any point in time are now more likely than earlier to have low long-term incomes. The choice of policy presumably hinges, at least in part, on the reasons for the decline in mobility, for example, whether it reflects rising barriers to opportunity, other shifts in the economy that have altered the distribution of market incomes, or changes in the U.S. tax and transfer system that increasingly reinforce rather than offset market disparities over time. This question represents a potentially fruitful avenue for future research.