Output Hysteresis and Optimal Monetary Policy

When an economy experiences a business cycle contraction, economic activity falls. In the event of a severe economic downturn, the losses can be long-lasting, and perhaps even permanent. In the United States, the Great Recession resulted in a slowdown in productivity growth, investment in research and development (R&D), and new firm entries. Ten years after the Great Recession began, despite the US economic recovery, the nation’s real gross domestic product (GDP) was still 15 percent below its pre-recession trend level; other advanced economies also experienced a similar drop in GDP.

Standard monetary policy theory is largely silent on how monetary policy decisions may interact with and influence the economy’s productive potential. This paper offers a model that addresses this question, based on an endogenous growth framework embedded in a New Keynesian setting. A temporary shortfall in aggregate demand, if incompletely stabilized by the central bank, can result in a permanent loss in potential output, which the authors define as output hysteresis. The mechanism is that a contraction in aggregate demand reduces the incentives for firms to invest in R&D, which leads to lower innovation that results in an endogenous slowdown in total factor productivity growth. The main goal of this paper is to analyze whether it is optimal for monetary policymakers to engineer a recovery in potential output back to the pre-recession trend, and how this goal might be accomplished. The model-based quadratic welfare loss function is comprised of three key market distortions: a wage inflation gap, a labor efficiency gap, and a productivity growth rate gap, which is novel to the endogenous growth framework and offers an additional rationale for stabilizing short-run business cycle fluctuations. The model focuses on liquidity demand and monetary policy shocks because monetary policy can counteract these shocks and maintain the economy at the first-best level, the equilibrium allocation that maximizes welfare.

Key Findings

Key Findings

- Away from the ZLB, an optimizing policymaker with the ability to commit to future policy actions (optimal commitment policy) sets interest rates to offset the permanent output gap. Following a strict inflation targeting rule achieves this goal. Hence, the central bank faces no tradeoff in stabilizing output and inflation, a result that Blanchard and Galí (2007) call the property of divine coincidence.

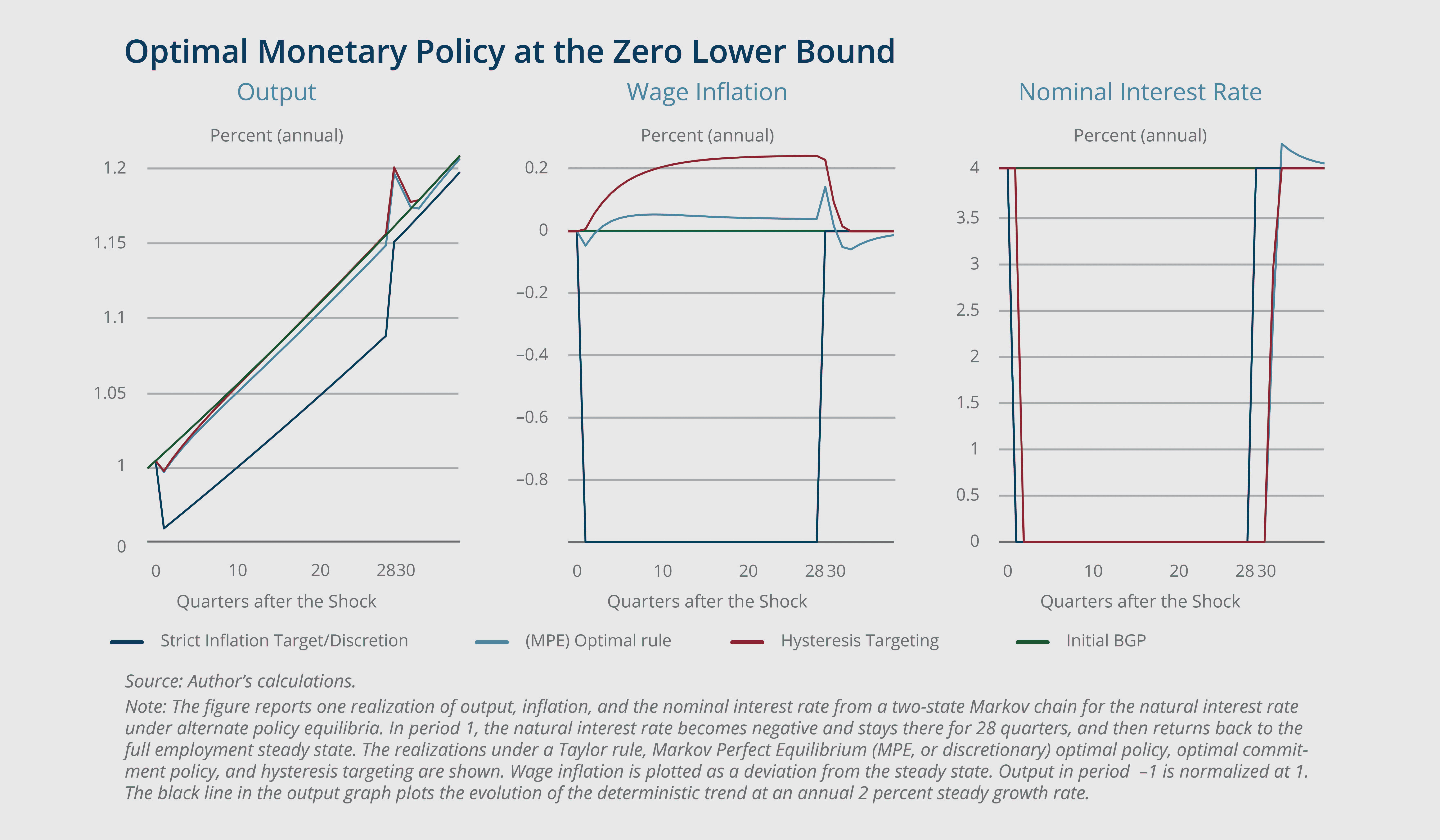

- A strict inflation target is unable to stabilize aggregate demand when the ZLB becomes a binding constraint, and admits output hysteresis. However, if the central bank targets zero output hysteresis, meaning that it commits to keeping interest rates lower until output returns to its initial trend, it can prevent output hysteresis whether or not the ZLB is binding. The hysteresis targeting rule signals the central bank’s commitment to running a high-pressure economy with no slack in employment, and thus raises the question of whether such a policy is desirable.

- When interest rates are at the ZLB, it is not possible to achieve divine coincidence, but policymakers can achieve welfare outcomes that come close to the outcomes that are possible when the ZLB is not a binding policy constraint. The optimal monetary policy response is a commitment to keeping future interest rates low in order to incentivize recovery close to the pre-recession productivity growth trend. This policy only entails a permanent output gap of 0.085 percent relative to the pre-recession trend, and thus almost completely returns the economy to the pre-recession trend.

- A central bank with an ability to commit to future policy actions (discretionary policy) does not find it optimal to undo the permanent output gaps that result following a ZLB period. The authors define this new dynamic inconsistency problem as the hysteresis bias, and recognize that the resulting output hysteresis is a consequence of the central bank’s lack of credible policy tools to engineer a full recovery in the pre-recession output trend, and thus is not due to mistakes made by monetary policy.

Exhibits

Exhibits

Implications

Implications

The long-run consequences of monetary policy constraints provides a reason for the central bank to pursue aggressive stabilization policies through implementable monetary policy rules during periods of severe shortfalls in aggregate demand. The 15 percent loss in US GDP a decade after the onset of the Great Recession suggests that even more aggressive monetary policy might be appropriate during a future ZLB episode.

Abstract

Abstract

We analyze the implications for monetary policy when deficient aggregate demand can cause a permanent loss in potential output, a phenomenon we term output hysteresis. In the model, the incomplete stabilization of a temporary shortfall in demand reduces the return to innovation, thus reducing total factor productivity growth and generating a permanent loss in output. Using a purely quadratic approximation to welfare under endogenous growth, we derive normative implications for monetary policy. Away from the zero lower bound (ZLB), optimal commitment policy sets interest rates to eliminate output hysteresis. A strict inflation targeting rule implements the optimal policy. However, when the nominal interest rate is constrained at the ZLB, strict inflation targeting is suboptimal and admits output hysteresis. A new policy rule that targets output hysteresis returns output to its pre-shock trend and approximates the welfare gains under optimal commitment policy. A central bank that is unable to commit to future policy actions suffers from hysteresis bias, as the bank’s inconsistent policy does not offset past losses in potential output.