Punishment and Crime: The Impact of Felony Conviction on Criminal Activity

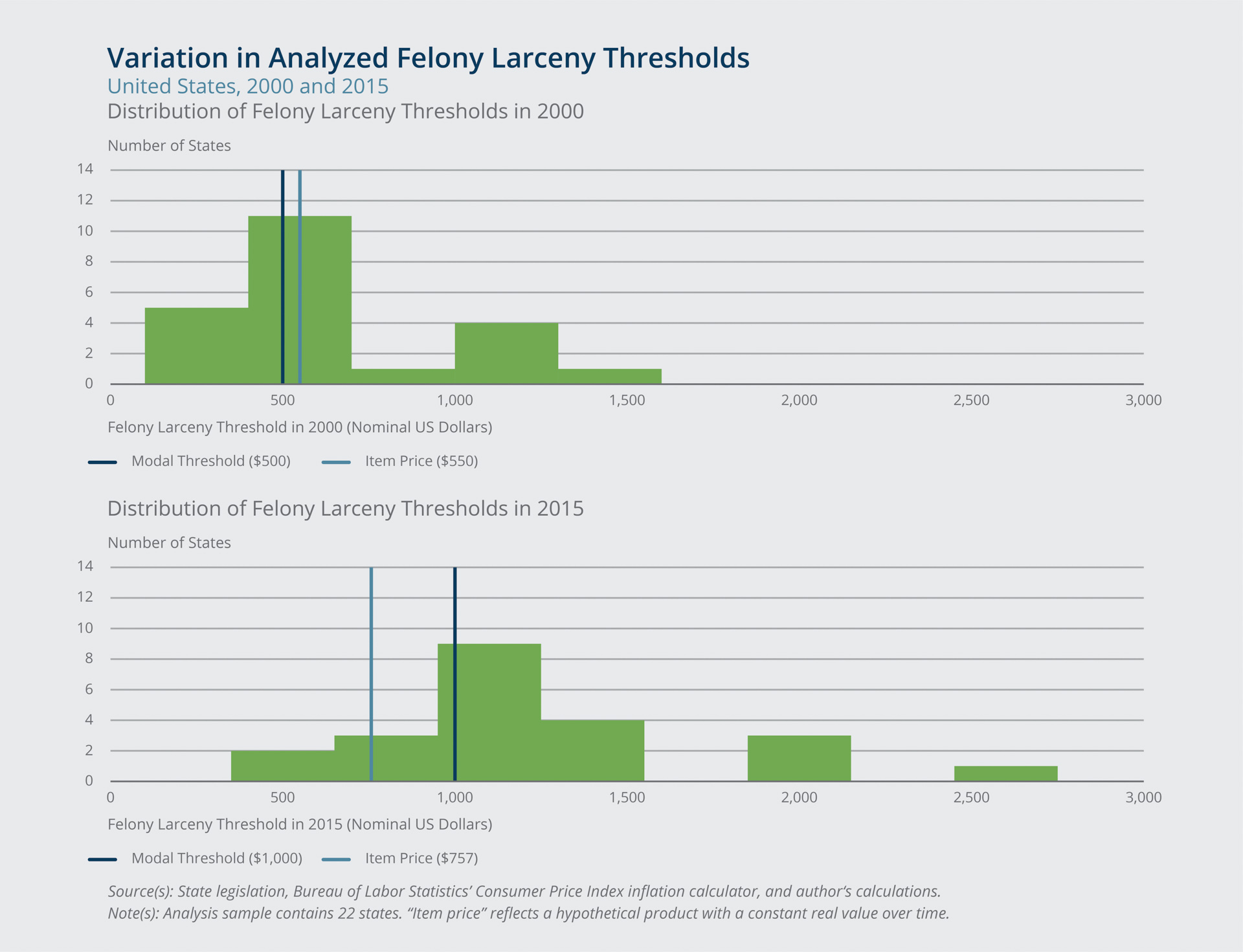

This paper examines the short-run and long-run effects of felony conviction on crime using increases in felony larceny thresholds as an exogenous, negative shock to felony conviction probability. A felony larceny threshold is the dollar value of stolen property that determines whether a larceny theft may be charged in court as a felony rather than a misdemeanor. Felony larceny threshold policy helps states govern felony convictions, thereby regulating punishment severity.

The author focuses on the theft value distribution between old and new larceny thresholds. In theory, this “response region” is where, following enactment of a higher threshold, the incentives to commit larceny of a given stolen value amount increase the most, because that crime switches from being a felony to a misdemeanor.

Key Findings

Key Findings

- In the short run (within 120 days of enactment), higher felony larceny thresholds cause a small, 2 percent increase ($20) in the response-region average larceny stolen value per incident.

- In the long run (within five years of enactment), increases in felony larceny thresholds lead to a 1 percent decrease ($8) in the response-region average larceny stolen value per incident.

- Also in the long run, larceny threshold increases cause a 10 percent increase (0.2 incidents per 1 million residents) in the response-region average daily jurisdiction larceny rate.

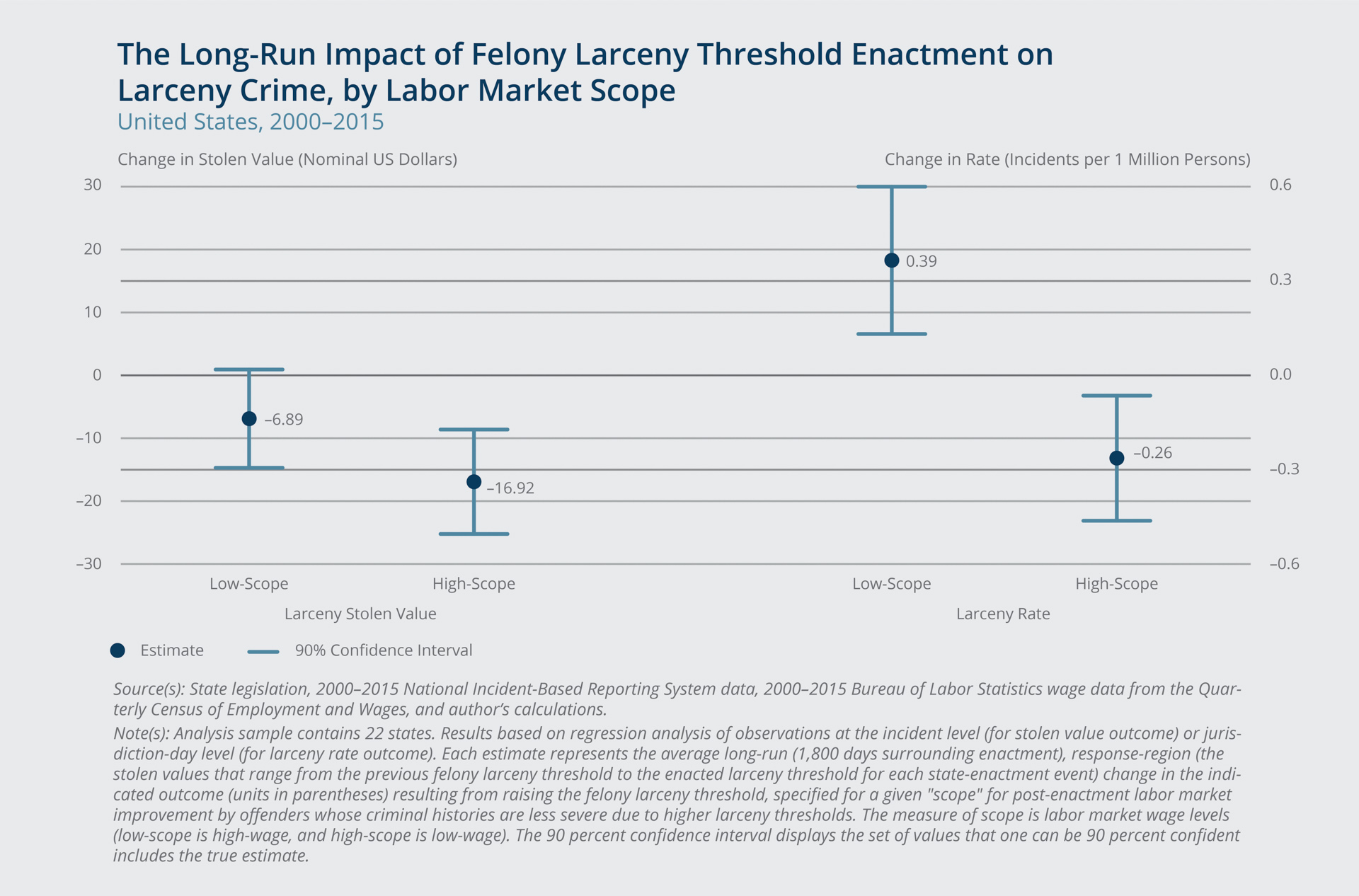

- In low-wage areas (which have a high scope for offender post-enactment labor market improvement), a higher larceny threshold causes a significant decline in response-region larceny stolen values (2 percent) and larceny rates (13 percent) in the long run. Conversely, in high-wage areas (which have a low scope for offender post-enactment labor market improvement), a higher larceny threshold leads to a significant increase in response-region larceny rates (19 percent) in the long run and no significant effect on larceny stolen values.

- Assuming symmetric but opposite effects of lowering larceny thresholds, these results suggest that increasing punishment severity through a higher probability of felony conviction decreases larceny crime in the long run in high-wage (low-scope) labor markets, but it actually increases larceny crime in the long run in low-wage (high-scope) labor markets.

- Descriptive evidence suggests that in both the short run and long run, higher felony larceny thresholds are associated with declines in criminal justice system severity and in the number of persons incarcerated.

- Short-run reductions in racial disparities for incarceration-related outcomes that are associated with larceny threshold increases do not appear to persist in the long run.

Exhibits

Exhibits

Implications

Implications

This paper’s findings suggest that the impact of punishment severity—namely, felony conviction probability—on criminal activity may differ by time horizon and labor market. These different effects should be taken into account when determining the optimal policies for criminal punishment. How short-run versus long-run outcomes and how focusing on low-wage versus high-wage areas affect social welfare may inform whether it is welfare-improving to increase or decrease punishment severity. That said, even in labor markets that may experience a long-run increase in larceny rates following enactment of a higher felony larceny threshold, raising the threshold likely results in savings from decreased incarceration rates that exceed the increased public cost from escalation in crime.

Abstract

Abstract

This paper uses increases in felony larceny thresholds as a negative shock to felony conviction probability to examine the impact of punishment severity on criminal behavior. In the theft value distribution between old and new larceny thresholds (“response region”), higher thresholds cause a 2 percent increase in the average larceny value within 120 days of enactment. However, within five years of enactment, response region average larceny values and rates decline 2 percent and 13 percent, respectively, in low-wage areas. Thus, under certain market conditions, smaller expected penalties may reduce incentives and deter crime in the long run.