“More funerals than weddings:” Opioids hit New England hard, devastating families, the economy

Pandemic worsened epidemic, but hope is found in community, perseverance

After they finished high school in the late 1990s, Kimberli Lovell and her friends could often be found partying in Portland, Maine. It was mostly alcohol and weed, sometimes cocaine.

“We were just kids, you know? … And then, oxy hit,” Lovell recalled. “It was like day and night. It was so fast, and it hit so hard.”

Suddenly, it seemed like everyone around Lovell was selling or taking “oxy,” short for OxyContin – a strong opioid typically prescribed for pain relief. Soon, many of her friends were also using heroin. In the next few years, six suffered fatal overdoses.

“By the time I was 30, I’d been to more friends’ funerals than weddings,” she said.

Her closest friend overdosed 10 days before Lovell’s first child was born in 2002. The birth of her daughter was a turning point in her life, Lovell said. She knew she had to get help.

“If I hadn’t had my daughter, I don't think I’d still be here,” she said.

In the following years, Lovell worked on her own addiction recovery and earned a certificate in behavioral health. Now, she leads the Bath Recovery Community Center in rural Sagadahoc County in Maine. The center is open to the public and offers support and resources for those struggling with addiction, as well as their friends and family.

Lovell said the center in Bath, a city of about 8,800, has grown a lot since it moved downtown in 2022. But she worries about what’s ahead. The impacts of widespread isolation during the pandemic are still being felt, she said. And she’s troubled by the rise of fentanyl – a synthetic opioid that’s up to 50 times stronger than heroin, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

2 images

“There’s fentanyl in everything now,” she said. “People are getting addicted quicker, and unfortunately overdosing and dying, because of it.”

The waves of overdoses from prescription opioids, heroin, and fentanyl aren’t unique to Maine. For years, researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston have been studying the opioid epidemic’s disproportionately high impacts across New England and its effects on the regional economy.

The epidemic is not selective. It plagues rural, urban, and suburban areas, extracting massive costs from people of all races, ages, and incomes. And according to the CDC, opioid overdose deaths rose significantly in the U.S. during COVID-19.

As the crisis evolves, residents are searching for ways to deal with present problems while heading off future threats. One thing they know: It’s critical to strengthen communities of people in recovery. Opioid addiction is a disease, they’ve learned, that thrives in isolation.

“Active addiction to any substance, but especially opioids, is very isolating,” Lovell said. “This is affecting people across the board, and there shouldn’t be any shame in talking about it.”

Opioid epidemic heated up in the late 2010s – then accelerated

Boston Fed researchers began studying the opioid epidemic in 2017, said Riley Sullivan, a senior policy analyst in the Bank’s New England Public Policy Center. That year, Americans became more likely to die from an accidental opioid overdose than a motor vehicle crash, according to the National Safety Council.

Since then, the Bank has published 10 reports related to the epidemic. The reports cover everything from its heavy fiscal impacts – including criminal justice and medical costs – to its potential effects on the workforce and the benefits of FDA-approved medications for opioid use disorder. Bank researchers have also studied how different New England states have approached the crisis, and their work highlights strategies from Vermont and Rhode Island that have since been emulated by other states.

Sign up for new research and data on the New England economy.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, opioid-related deaths nationwide rose to nearly 81,000 in 2021. That’s an increase of more than 60% in just two years, Bank researchers said in a recent paper.

In New England, the rate of overdose deaths was higher than the national average in 2021 in every state but New Hampshire, according to the CDC. Maine was highest in the region and the fifth-highest in the U.S. In 2022, more than 2,300 people in Massachusetts alone died of opioid-related overdoses – an all-time high, according to the state Department of Public Health.

Senior Bank economist and policy advisor Mary Burke said the epidemic was initially driven by prescription opioids such as OxyContin, partly due to an early misconception that they had a low incidence of addiction. Then, once pills became more regulated, people who had developed addictions turned to street drugs like heroin.

“You see the death rates in New England spiking much higher then, going above the national average,” she said.

Bank researchers say the opioid crisis not only increases deaths, it can also prevent people from working or negatively affect their employment, and all those things take a huge fiscal toll. For instance, Sullivan found in a 2018 report that state governments in the region have spent “significantly higher than the per-state national average” in past years to address the epidemic.

In a report from 2020, Burke and Sullivan used data from Rhode Island to show that methadone and buprenorphine – two FDA-approved medications for the treatment of opioid use disorder – were both associated with lower repeat-overdose rates, and policies designed to expand access to buprenorphine appear to have been successful in Rhode Island. In a separate report from 2022, they found that patients had greater success in finding a job after starting treatment with buprenorphine.

Sullivan said it’s difficult to pinpoint why opioids have hit New England so hard. The Bank’s research has confirmed work by others who found that counties with elevated rates of prescribing opioids later had elevated rates of fatal overdoses, he said.

“But there are many other contributing factors,” he added.

Opioid crisis compounds generational impacts of addiction in Worcester

2 images

Bridget Del Rio stood over a purple flower box on a small patio behind the Everyday Miracles Peer Recovery Support Center in Worcester, Mass. Fabric blossoms and real ones were planted side by side.

“Most of the women who made this are no longer with us,” said Del Rio, the center’s assistant program director.

Del Rio’s own addiction history doesn’t involve opioids. But the recovery coach knows the challenges people struggling with addiction often face, including homelessness and domestic violence. Parents who are their children’s primary caretakers also face more barriers to getting into treatment, she said.

“I can say that as someone working in the field and coming from the streets, it can happen to anybody,” she said.

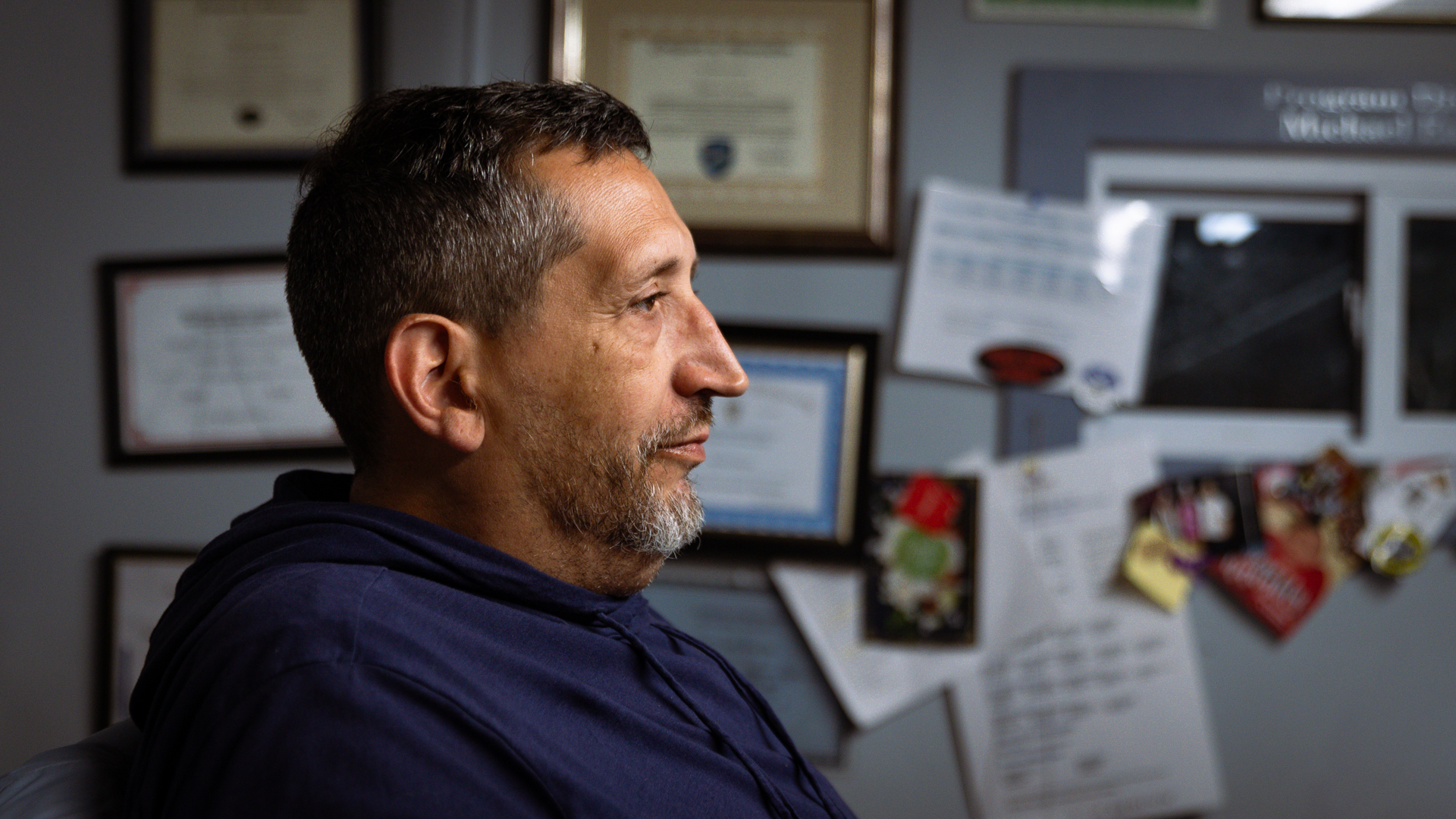

Worcester is the second-largest city in Massachusetts, with about 206,000 residents. Between 2015 and 2022, it had 1,059 opioid-related overdose deaths – including a record 168 in 2022, according to the state Department of Public Health. But to fully understand the epidemic in Worcester, the generational impacts of addiction must be recognized, said Michael Earielo, the program director of Everyday Miracles.

“My father had an opiate problem back in the 1970s when I was growing up here,” he said. “But it was swept under the rug because it was Black and brown people. … It was ‘that side of the street.’”

The crack cocaine epidemic hit the central Massachusetts city hard in the 1980s, and by age 13, Earielo and his friends were already using it. Later, he began using heroin.

2 images

“Back then, there was no rush to get us into treatment. It was, ‘Lock them up,’” said Earielo, now 53 and in long-term recovery. “Now that it’s the suburban kids getting addicted … that’s changed dramatically.”

Tim Rassias, who has founded addiction treatment centers in Worcester and Ashby, Mass., said that the longer a person remains sober, the better a shot they have at long-term recovery.

But to stay sober, people need a “continuum of care,” Rassias said. It usually starts with detox, or “acute treatment services.” That’s followed by a residential program with round-the-clock care, or “clinical stabilization services.” From there, people may progress to outpatient services, living at home while being treated on a regular schedule.

Rassias said he’s especially concerned about a lack of access to beds in the clinical stabilization phase.

“When people finish detox, and there’s no beds available in stabilization, they usually end up back on the street,” he said. “But their tolerance has changed. They take something that has fentanyl, and it’s very likely that they overdose.”

As the pandemic's isolation stretched on, overdose deaths in Maine spiked

2 images

The Bath Recovery Community Center is less than a five-minute walk from city hall and the Kennebec River waterfront. Inside, Cody Morrill leans against a couch and talks about the dreams people have about using when they’re new to sobriety.

“You’ll wake up craving it. And if you don’t do something about it immediately, chances are you’re going to relapse,” he said. “The best thing to do is to call someone, but a lot of people are afraid to.”

The 27-year-old is becoming that person to call, ever since Lovell hired him as a recovery coach. Morrill said many of the people he grew up with in Randolph, Vermont, used drugs, including his father. He dabbled in weed and alcohol as a teen but avoided opioids – until a motorcycle accident about seven years ago landed him in the hospital. There, Morrill said he was given morphine and Percocet. Once he ran out and couldn’t find them on the street, he turned to heroin.

“I was completely against heroin. I absolutely did not want it in my life,” he said. “But the next thing I knew, I was doing it.”

Morrill said during the pandemic, overdoses went “through the roof” as isolation stretched on and dealers added more fentanyl to their products. The Maine Drug Data Hub shows a rise in overdose deaths after COVID-19 started, with a 33% increase between 2019 and 2020, primarily driven by fentanyl.

Morrill said he used opioids on-and-off until January 2022. Later that year, he moved to Maine.

“It took me four tries to really get a grasp on rehab, because I kept going back home – and that’s not a good idea at first,” he said.

As a recovery coach, Morrill works with anyone who walks into the center, from people who aren’t ready to stop using to those who’ve been sober for years.

The support system in Bath is relatively strong, and many local businesses hire people in recovery, Morrill said. But he said funding remains a big issue for people entering sober living, and there’s a lack of facilities for women.

There’s always a new challenge, Morrill added. It could be getting people food and clothes, getting them into detox, or just helping them cope with obstacles they didn’t anticipate.

“That’s a big one,” he said. “Even people who are five years sober run into new triggers.”

Narcotics Anon member: Strengthening communities of people in recovery critical as fentanyl spreads

2 images

William Jenkinson knows the challenges faced by the newly sober. His first year of what he calls “real recovery” – sober from both legal and illegal substances – has been a rough one, he said. The Brockton, Mass., native was introduced to OxyContin by a friend’s father in high school. Then, he started selling it for the man after he got laid off and slowly became addicted. At age 18, he turned to heroin because it was cheaper.

Now in his early 30s, Jenkinson credits Narcotics Anonymous with saving his life. In the past year, his mother died, his younger cousin overdosed on fentanyl, and he had heart surgery. But he didn’t feel the “obsession to use” over any of those devastating events, he said.

“That’s the best gift I could ever receive – and having people in my life today that really care about my well-being, because we’ve been through the same things,” he said.

Jenkinson said that as widely discussed as the opioid epidemic is, the stigma associated with it remains strong. That makes it even more challenging for people to reach out for help – and more important to build connections between people in recovery, who can relate to and support each other.

“Even at work, I’m honest about my addiction and recovery,” he said. “It’s a good feeling when someone reaches out to you for help.”

Those strong communities of people in recovery are only going to become more critical as fentanyl gains popularity among teens and young adults, Jenkinson said. That’s one reason he and Lovell started Narcotics Anonymous meetings in Bath. He also wants to continue building up a social scene in Bath for people in sobriety.

“This is a central location for people in other towns, too,” Jenkinson said. “We've had so many people show up, and it's just getting bigger and bigger.”

Looking ahead: Recovery “has a voice now,” but more progress is needed

The communities of people in recovery are well-established in Worcester, in part because of the city’s long history of dealing with addiction.

Everyday Miracles, part of Spectrum Health Systems, sees about 80-120 visitors each day, and it has several hundred members, said Earielo, the program director. Many people come from out of town to get treatment in Worcester, although a core group of members are from the city. Most are struggling with an opioid use disorder, he said.

The center hosts several programs each day, from parenting groups and anger management classes to all-recovery meetings and overdose awareness sessions. It also collects donations and has a kitchen for members to use.

Worcester District Attorney Joe Early regularly works with Everyday Miracles and other community groups through his office’s Opioid Task Force. He emphasized the importance of building up a recovery support “ecosystem.”

“People can’t prioritize sobriety when they’re worried about survival,” he said. “Basic human needs must be met first.”

For instance, the district attorney's office created a county-wide system that sends recovery coaches to residents’ houses within 24 to 48 hours after an overdose is reported, Early said. Through that program, the city has learned more about the trauma children face after watching a family member overdose, and it’s dedicated federal funding toward helping them.

As Jenkinson helps support people in recovery in Maine, he’s got a wary eye on the future. In addition to the rise of fentanyl, Jenkinson said he’s also concerned about cases of overprescription and illegal sales of medications intended for treating opioid use disorder, such as Suboxone, which contains buprenorphine.

“It’s being sold to kids who aren’t even into opioids, and that’s getting them hooked. Then once they can’t get it, they start getting into street drugs,” he said. “It’s a whole ‘nother issue.”

Lovell, of the Bath Recovery Community Center, said she’s seen a lot of progress over the past 20 years when it comes to public awareness of addiction and access to resources. People in recovery have a real voice now, she said. But there’s still much further to go.

“We need to continue talking about this, so people don’t feel alone – and that goes for the person with substance use disorder, as well as their families,” she said. “It’s an entire community issue. It’s a human issue.”

Media Inquiries?

Contact our media relations team. We connect journalists with Boston Fed economists, researchers, and leadership and a variety of other resources.

About the Authors

About the Authors

Amanda Blanco is a member of the communications team at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

Email: Amanda.Blanco@bos.frb.org

Site Topics

Keywords

- opioid use disorder ,

- New England ,

- Maine ,

- Massachusetts ,

- COVID-19 pandemic