What Are the Consequences of Global Banking for the International Transmission of Shocks? A Quantitative Analysis

Large banks with a global presence play an important role in the transmission of shocks across borders. The sheer size of foreign banking institutions and their involvement with the real economy makes them important vehicles for the global transmission of shocks. For example, foreign banks hold about 25 percent of the assets in the US banking system. The Japanese banking crisis of the early 1990s had a substantial effect on the credit supply in the United States. In this working paper, we find that after the 2010 European sovereign debt crisis, US branches of parent banks that were exposed to GIIPS sovereign debt (meaning the government debt in Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain) cut their assets by 54 percent, representing roughly $427 billion and 8 percent of total US bank assets. In more recent related work, we estimate that an Italian sovereign or banking crisis in the current environment could cause a decline of as much as 20 percent in aggregate US bank assets.

Regulatory reforms should not only be reactive to crises, but also proactive to reduce the likelihood and limit the severity of such crises. A reform implemented in 1991 prohibited foreign branches from accepting uninsured retail deposits. Likewise, the financial crisis of 2008 and the 2010 European sovereign debt crisis prompted a wave of regulatory reforms that affected large banks in particular, including those with a global presence. For example, one of the provisions of the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act required foreign banks with more than $50 million in US subsidiary assets to consolidate all of their subsidiaries under a single bank holding company by 1 July 2016. This is known as the Intermediate Holding Company (IHC) requirement, and its goal was to mitigate the transmission of foreign shocks into the US credit markets. Incidentally, US branches owned by foreign banks were – and remain – exempt from this requirement, in the sense that assets held in branches did not count toward the $50 billion IHC threshold. As one may expect, foreign banks reacted strategically, implementing a series of changes in their operations and legal structures in response to the IHC requirements.

In this context, we develop a quantitative structural model of global banking that can be used to evaluate ex ante the effects of policy reforms. Our work contributes to the global banking literature in two important ways. First, while earlier contributions overlook the importance of a bank's mode of operations, our model provides a microfoundation for a bank's decision of whether and how to enter a foreign market – through branches or through subsidiaries. Second, while most studies employ reduced-form empirical analysis, our quantitative model enables us to study the cross-border effects of demand shocks and regulatory changes via comparative statics and counterfactual analysis, respectively.

Key Findings

Key Findings

- US branches of European banks exposed to the 2010 debt crisis experienced a reduction in the supply of wholesale deposits, which represented a funding shock for US branches. Faced with solvency problems in their foreign branches, European parents used their internal capital market to support profitable lending in their US branches. Nonetheless, US branches decreased their total lending in the United States.

- On the other hand, foreign subsidiaries' balance sheets are more isolated from the shock that affects their parents. As a result, there was no direct effect on their assets and liabilities as a result of the 2010 European debt crisis.

- The results of our simulation exercises suggest that increased capital requirements, the elimination of branching, or an ad hoc monetary policy intervention would have mitigated the negative effects of the 2010 crisis on US aggregate lending. Conversely, the elimination of subsidiarization would have caused an even more severe decline in banking activity in the US.

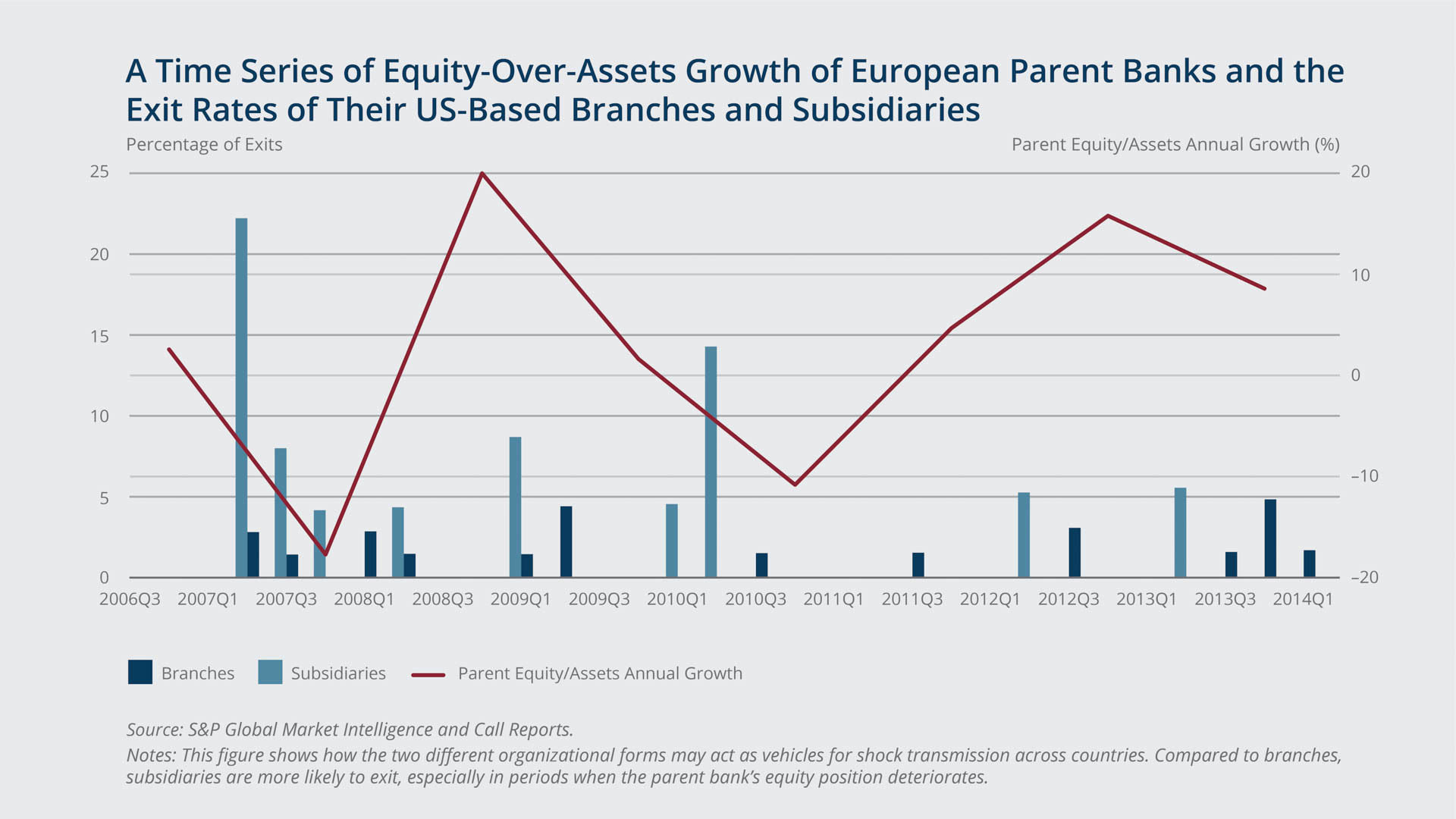

- Our model also has implications for the possible response of foreign bank organizations to large shocks to their parent institutions. More precisely, frictions to the internal capital market between parents and subsidiaries imply that, following a large shock, a parent bank may repatriate funds by shutting down its foreign subsidiaries. In related work, we simulate an economy to quantify the effects of a sovereign crisis in Italy under the current US banking industry structure. French, Spanish, German, and British bank holding companies are heavily exposed to Italian sovereign and bank debt. Our model predicts that if these exposed large bank holding companies were subject to a 50 percent equity loss, their US branches would suffer an 85 percent flight of deposits and overall credit in the United States would decline by 21 percent as a result of branches shrinking, subsidiaries exiting, and the exposure of large domestic banks to foreign markets.

Exhibits

Exhibits

Implications

Implications

Our most important finding clarifies the relationship between global banks' organizational structure and shock transmission. We show that subsidiarization isolates a global bank's balance sheets by location; hence, subsidiarization mitigates contagion. However, subsidiarization is associated with a limited internal capital market between the parent and affiliate, so that the parent does not have instruments to dampen the global effect of shocks. This limitation results in possible reorganizations and exits from the foreign market. Conversely, branching can take advantage of an internal capital market within a global bank, smoothing the effect of a shock across countries and reducing its global impact. Our analysis shows that global banks’ organizational choices have a quantitatively important effect on the transmission of shocks.

Abstract

Abstract

The global financial crisis of 2008 was followed by a wave of regulatory reforms that affected large banks, especially those with a global presence. These reforms were reactive to the crisis. In this paper we propose a structural model of global banking that can be used proactively to perform counterfactual analysis on the effects of alternative regulatory policies. The structure of the model mimics the US regulatory framework and highlights the organizational choices that banks face when entering a foreign market: branching versus subsidiarization. When calibrated to match moments from a sample of European banks, the model is able to replicate the response of the US banking sector to the European sovereign debt crisis. Our counterfactual analysis suggests that pervasive subsidiarization, higher capital requirements, or ad hoc policy interventions would have mitigated the effects of the crisis on US lending.