The Underutilized Potential of Teacher-Parent Communication

Though still the exception rather than the rule, teacher-parent communication can have strong positive effects on students' success in school.

There is widespread agreement among educators and parents that communicating with each other benefits students. However, evidence suggests that teacher-parent communication is infrequent and unsystematic in most schools.

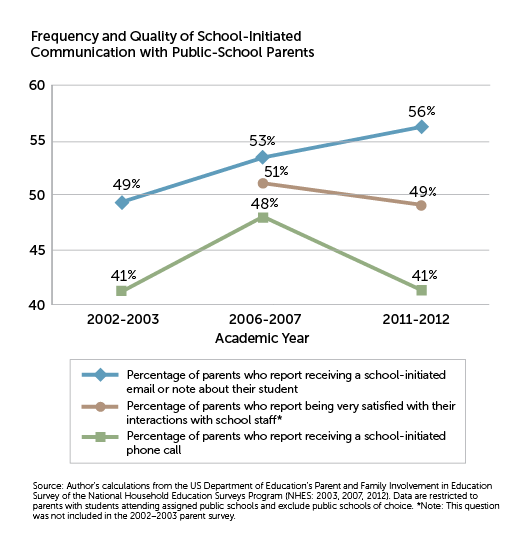

The best information on the frequency of communication between schools, teachers, and parents comes from the nationally representative Parent and Family Involvement in Education survey.[1] Data collected on the frequency and quality of school-initiated communication with public-school parents from 2003 to 2012 show that although the percentage of parents who report having ever received an email or note about their student has gone up, calls home have gone down since 2007, as has the percentage of parents who say they are "very satisfied with their interactions with school staff." (See "Frequency and Quality of School-Initiated Communication with Public-School Parents.")

There are three main takeaways from the data. First, communication in any form between schools, teachers, and parents is surprisingly rare. For example, 59 percent of public-school parents report never receiving a phone call home in 2012. Second, there is considerable room for improvement in the quality of communication. About half of all parents are not "very satisfied" with their interactions with school staff. Third, overall trends across the last decade suggest schools are not making much progress in improving the frequency and quality of communication with parents.

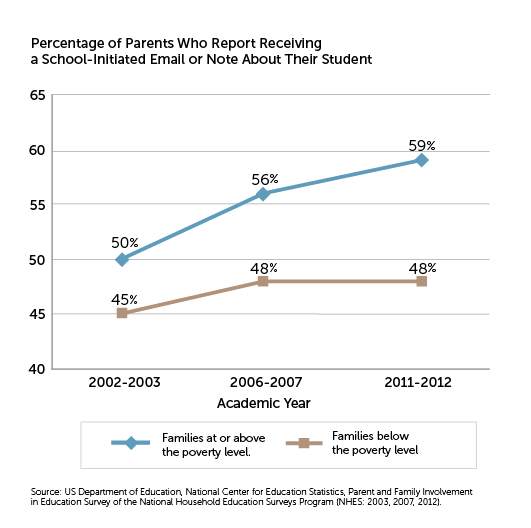

Although the use of email as a form of communication has increased steadily over the last decade, this increase has not benefitted all families equally. Email communication with families living at or below the poverty line has remained flat since 2007. The income-based "email communication gap" between families above and below the poverty line has more than doubled. (See "Percentage of Parents Who Report Receiving a School-Initiated Email or Note.")

The Power of Teacher-Parent Communication

These statistics should sound alarm bells, given growing causal evidence that communication can empower parents and improve students' academic performance.

For example, a small randomized control trial that Shaun Dougherty and I conducted during a charter school summer academy demonstrated that frequent phone calls home immediately increased students' engagement in school as measured by homework completion, in-class behavior, and in-class participation.[2]

In a related experiment, Todd Rogers and I found that sending parents weekly one-sentence individualized messages from teachers during a high school summer credit-recovery program reduced the percentage of students who failed to earn course credit by 41 percent.[3]

Additionally, a fascinating experimental study conducted in France found that inviting parents to attend three two-hour meetings with school leaders to talk about how to support their students in the transition to middle school increased both parents' and students' engagement in school.[4] Parents who were randomly chosen to receive invitations to the meetings were more likely to join the parent association and monitor their child's schoolwork, while their students' attendance, behavior, and performance in French class increased.

Implementation Barriers

Three primary factors are contributing to the low rate of teacher-parent communication: implementation barriers, time costs, and the absence of schoolwide communication policies. Implementation barriers include the lack of easy access to parent contact information, outdated contact information records, language barriers between teachers and parents, and the lack of noninstructional time teachers have to make calls or send texts or emails during the school day. Many of these are technical challenges that schools can address with systematic efforts to update contact information, translation software and services, and data management systems with user-friendly teacher dashboards.

Providing dedicated time during the workday for teachers to reach out to parents is a more difficult challenge. One option would be to relieve teachers of noninstructional responsibilities that could be performed by less costly teachers' aides or parent volunteers. Another would be to increase the amount of noninstructional time in teachers' contractually obligated workdays, as Boston Public Schools recently did in their expanded school-day initiative.[5] A third option is to enhance the efficiency of the time that teachers already spend communicating with parents.

Detailed time-use data for educators is hard to come by. However, a time-use study of a random sample of classroom teachers in Washington State found that teachers spend approximately 8 percent of their noninstructional work hours communicating with parents—about one hour each week.[6] In ongoing work, Jason Grissom and Susanna Loeb have found that principals spend even less time communicating with parents—as little as 3 percent of their workday. Although less than ideal, even secondary-school teachers who work with over 100 students would be able to speak with every parent at least once during the school year for 10 minutes if they dedicated just 30 minutes a week to making phone calls. And a growing body of research demonstrates that text messages provide an efficient and effective way to reach parents with individualized messages on a more frequent basis.[7]

The lack of guidance and clear expectations around teacher-parent communication is arguably the most commonly overlooked factor. Beyond general encouragement by administrators to contact parents, teachers are left to determine when, how, and why they should reach out. Reducing the income-based email communication gap requires both increasing access to email and proactive communication policies designed to distribute teacher-initiated communication across all families. The rapidly increasing access to mobile phones even among low-income families presents an opportunity to connect with all families using communication technology and to increase the efficiency of the communication.

Without formal expectations, sufficient time, and the necessary communication infrastructure, teachers often take a passive approach to communication as they shift their attention to other tasks. Promoting more transparency around the frequency with which each staff member is contacting parents could also serve to foster positive peer effects among teacher teams. It is well within our ability to make teacher-parent communication the norm rather than the exception.

Matthew Kraft is an assistant professor of education and economics at Brown University in Providence. He can be contacted at mkraft@brown.edu and on twitter @MatthewAKraft.

Endnotes

- Amber Noel, Patrick Stark, and Jeremy Redford, "Parent and Family Involvement in Education, from the National Household Education Surveys Program of 2012" (report, National Center for Education Statistics, US Department of Education, Washington, DC, 2015), https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2013028rev.

- M.A. Kraft and S.M. Dougherty, "The Effect of Teacher-Family Communication on Student Engagement: Evidence from a Randomized Field Experiment," Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness 6, no. 3 (2013): http://scholar.harvard.edu/mkraft/publications/effect-teacher-family-communication-student-engagement-evidence-randomized-field.

- M.A. Kraft and T. Rogers, "The Underutilized Potential of Teacher-to-Parent Communication: Evidence from a Field Experiment," Economics of Education Review 47 (2015): http://scholar.harvard.edu/mkraft/publications/underutilized-potential-teacher-parent-communication-evidence-field-experiment.

- F. Avvisati et al., "Getting Parents Involved: A Field Experiment in Deprived Schools," Review of Economic Studies 81 (2014): http://www.povertyactionlab.org/publication/getting-parents-involved-field-experiment-deprived-schools.

- James Vaznis, "Longer School Day for Boston Schools Wins Final Approval," Boston Globe, January 29, 2015, https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2015/01/28/longer-school-day-for-boston-schools-wins-final-approval/S8FBcJqTnbA9jaZzSmVo1J/story.html.

- "How Washington Public School Teachers Spend Their Work Days" (report, Central Washington University, Ellensburg, Washington, 2015), http://www.cwu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/teachertimestudy.pdf.

- B.L. Castleman, The 160-Character Solution (Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015), https://jhupbooks.press.jhu.edu/content/160-character-solution.

Articles may be reprinted if Communities & Banking and the author are credited and the following disclaimer is used: "The views expressed are not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston or the Federal Reserve System. Information about organizations and upcoming events is strictly informational and not an endorsement."

About the Authors

About the Authors

Matthew A. Kraft, Brown University