Equal Pay for Women Would Decrease US Poverty

Equal pay for working women is an essential lever for decreasing family poverty and growing the US economy.

Women make up nearly half the US workforce, and their earnings are essential to the economic security of millions of families. Yet women who work full-time and year-round earn only 78 cents on the dollar compared with men who work full-time and year-round . In 2013, the last year for which median annual earnings for full-time workers are available, the gender wage gap at the median was $11,053.[1] The glass ceiling and occupational segregation-the concentration of women in some jobs and men in others-remain stubborn features of the labor market.[2]

New Findings

Each state reflects the national picture, as shown in "The Status of Women in the States 2015: Employment and Earnings," by the Institute for Women' s Policy Research (IWPR).[3] In general, women in the New England and Mid-Atlantic states fare the best on an employment-and-earnings composite, an index that includes the wage ratio, median annual earnings, percent of women in the labor m arket, and percent employed in professional or managerial occupations. Five of the six New England states are ranked in the top 12 states and earn a grade of B or a B+. Maine is ranked 19th (still above the median state), earning a C+ on the composite.

Despite the mostly positive composite scores, no New England state has reached pay equity. Vermont, Maine, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts have high female-male ratios (at 86 percent, 84 percent, 83 percent, and 81 percent respectively) and hence the smallest wage gaps in the region (14 percent, 16 percent, 17 percent, and 19 percent). Connecticut and New Hampshire have a larger gap (23 percent), ranking 34th and 38th. Vermont (4th), Maine (8th), and Rhode Island (11th) rank within the top states nationwide for pay equity, and Massachusetts ranks 18th, well above the median. For Connecticut, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire, however, the pay-equity rank is their lowest rank among the four components of the composite. For Maine and Vermont, pay equity is their best score on any indicator in the composite.

Many differences between the states affect pay equity, including what industries predominate in a state, women's educational attainment, and the friendliness of state policies toward working women (higher minimum wages, more collective bargaining, publically provided child care, and on-the-job accommodations for pregnant workers).

The racial composition of a state's workforce also is significant. Because minority men earn substantially less than white men, whereas minority women earn less than white women but not as much less, a state with a large minority population often has a higher female-to-male pay ratio.

In 2014, Hispanic men earned at the median only about 68 percent of what white men earned weekly; Hispanic women earned 75 percent of what white women earned. Black men earned about 76 percent of what white men earned; black women earned 83 percent of white women's earnings. Still, the pay gap between women of color and white men is large. Hispanic women's median weekly earnings in 2014 were 61 percent of white men's, and the median weekly earnings of blac k women were 68 percent of white men's. Women of all major racial and ethnic groups also earn less than men in their own ethnic group.[4]

Of the 71 percent of US mothers who work for pay, 68 percent are married, typically with access to men's incomes, but married mothers' earnings are nevertheless important to families.[5] It is estimated that about 37 percent of working mothers are either joint breadwinners (earning at least 40 percent of the household income) or p rimary breadwinners.[6] Thirty-two percent are single mothers-often the family's sole support. And many women without children support themselves and other relatives.

Equal pay would greatly benefit women and their families. Yet IWP R's straight-line projection shows that at the same rate of progress since 1960, equal pay will not be realized until 2058.[7] The likely year in which pay parity is reached depends on the starting year of the projection and the method use d. A 1960 start includes the period of men's rapidly rising wages. Starting in the late 1970s, when men's real wages began to stagnate, shortens the time to pay parity. Including only the most recent 10 years would lengthen the time because, in this period, both women's and men's real wages show little growth. In an alternative method, still using 1960 as the starting date and the straight-line method but making the calculation separately for men's and women's wages, pay parity arrives in 2080.

What If?

IWPR researchers also calculated how much women would gain in earnings, how much poverty would be reduced, and how much the economy would be likely to grow if women earned pay equal to that earned by comparable men.

Labor supply, human capital, and labor-market characteristics (urban, rural, and regional) were statistically controlled in the calculation. Nationally, 59.3 percent of women would earn more if working women were paid the same as men of the same age with similar education and hours of work in the same type of labor market.

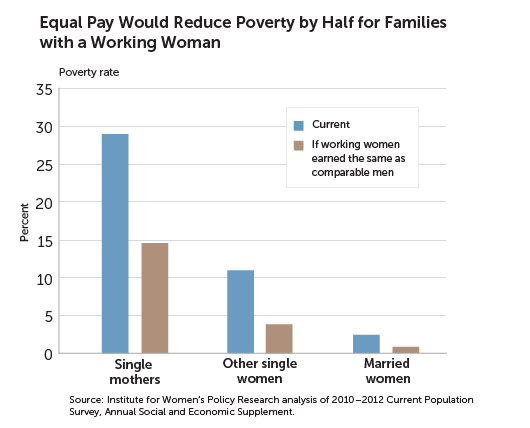

Providing equal pay to women would also have a dramatic impact on their families. (See "Equal Pay Would Reduce Poverty by Half.") The poverty rate for all working women would be halved, falling to 3.9 percent. For the 36.2 million families headed by married women, the poverty rate would fall by more than half, from 2.4 percent to 1.1 percent. The high poverty rate for working single mothers would fall by nearly half, from 28.7 percent to 15.0 percent, and two-thi rds would receive a pay increase. For the 14.3 million single women, equal pay would mean a very significant drop in poverty from 11.0 percent to 4.6 percent. The average woman worker is estimated to gain $6,251 in annual pay (which includes $0 values for those who gain nothing).

To the extent women's lower pay is due to discrimination, it's a market failure resulting in the misallocation of human capital. It contributes to women working at less productive pursuits, which holds back economic growth. Some, possibly many, women who are crowded into lower-paying, female-dominated occupations (for example, cashiers, child-care workers, and personal-care aides) have the skills to work in higher-paying jobs that are dominated by men. IWPR researchers estimated that the US economy would have produced additional income of $447.6 billion if women received equal pay . That represents 2.9 percent of 2012 gross domestic product, or the addition of a state the size of Virginia. And that estimate is low, since women's work hours, educational achievement, and occupational attainment were not increased in the model, and women almost surely would upgrade those factors if they expected to receive equal pay.

One barrier to equal pay has been pay secrecy. In 2014, California, Colorado, Illinois, Louisiana, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Jersey, and Vermont pas sed laws prohibiting retaliation against workers who share pay information.[8] The laws appear necessary: in 2010, nearly half of all workers nationwide reported being forbidden or strongly discouraged from discussing their pay with colleagues.[9] The federal government, which has high levels of pay transparency, has a gender wage gap of only 11 percent, compared with 22 percent across the economy.[10]

Pay transparency alone will not close the gap, however. Transparency needs to be combined with strengthened enforcement of equal employment opportunity laws, a higher minimum wage, increased union representation and collective bargaining, and more family-friendly policies.

Approaches that raise wages at the bottom, such as increases in the minimum wage and collective bargaining, are especially important to women since they hold a disproportionate share of low-wage jobs. The gender wage gap being smaller among union members, collective bargaining a lso raises wages more for women and minorities on average than for white men.

The lowest-paid workers are the least likely to receive any kind of leave benefits, especially paid sick days and paid family leave. Married women with high-earning husbands may take time off work for a baby without a disastrous effect on family finances, but low- and moderate-wage women are typically married to men with low or moderate wages, which makes the loss of their earnings more deleterious. Paid sick days and paid family leave would help new mothers maintain family income while having time to recover and take care of their babies' health needs.

The increased labor-market attachment and longer job tenure with which family leave is associated should also help raise w omen's wages-and for low-wage women's lifetime earnings, strengthening and lengthening labor-force attachment is essential.

Any policy that benefits women in the workforce is going to be important for improving the lives of their family members.

Heidi Hartmann, PhD, an economist, is president and CEO of the Institute for Women's Policy Research, where Elyse Shaw, MA, is a research associate. They are based in Washington, DC. Contact the authors at hartmann@iwpr.org or shaw@iwpr.org.Endnotes

- Carmen DeNavas-Walt and Bernadette D. Proctor, "Income and Poverty in the United States: 2013" (report, U S Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 2014), http://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2014/demo/p60-249.pdf. The da ta are derived from the Annual Social and Economic Supplement of the Current Population Survey.

- Ariane Hegewisch, Hannah Liepmann, Jeffrey Hayes, and Heidi Hartmann, "Separate and Not Equal? Gender Segregation in the Labor Market and the G ender Wage Gap" (briefing paper #C377, Institute for Women's Policy Research, Washington, DC, 2010), http:// www.iwpr.org/publications/pubs/separate-and-not-equal-gender-segregation-in-the-labor-market-and-the-gender-wage-gap.

- "The Status of Women in the States" (report #R401, Institute for Women's Policy Research, Washington, DC, 2015), http://www.iwpr.org/publications/pubs/the-status-of-women-in-the-states-2015-2014-employment-and-earnings. The state-by-state equal-pay ratios are based on microdata analysis by IWPR of the American Community Survey for 2013.

- Ariane Hegewisch, Emily Ellis, and Heidi Hartmann, "The Gender Wage Gap 2014: Earnings Differences by Race and Ethnicity" (fact sheet #C430 , Institute for Women's Policy Research, Washington, DC, 2015), http://www.iwpr.org/publications/pubs/the-gender-wage-gap-2014 -earnings-differences-by-race-and-ethnicity. The weekly earnings data are from the Current Population Survey as reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- Heidi Hartmann, Jeff Hayes, and Jennifer Clark, "How Equal Pay for Working Wome n Would Reduce Poverty and Grow the American Economy" (briefing paper #C411, Institute for Women's Policy Research, Washington, DC, 2014), http://www.iwpr.org/publications/pubs/how-equal-pay-for-working-women-would-reduce-poverty-and-grow-the-american-economy.

- Ariane Hegewisch and Jessica Milli (unpublished microdata analysis of the American Co mmunity Survey for 2013, Institute for Women's Policy Research, Washington, DC, 2015), forthcoming in The Status of Women in the States: 2015 (Institute for Women's Policy Research, Washington, DC, 2015).

- "Women's Median Earnings as a Percent of Men's Median Earnings, 1960-2013" (quick figures #Q026, Institute for Women's Policy Research, Washington, DC, 2014), http://www.iwpr.org/publications/pubs/women2019s-median-earnings-as-a-percent-of-men2019s-median-earnings-1960-2013-full-time-year-round-workers-with-projection-for-pay-equ ity-in-2058.

- "Pay Secrecy" (report, US Department of Labor, Women's Bureau, Washington, DC, 2014), http://www.dol.gov/wb/media/pay_secrecy.pdf.

- Jeff Hayes and Heidi Hartmann, "Women and Men Living on the Edge: Economic Insecurity after the Great Recession" (report #C386, Institute for Women's Policy Research Washington, DC, 2011), http://www.iwpr.org/publications/pubs/women-and-men-living-on-the-edge-economic-insecurity-after-the-great-recession.

- Ariane Hegewisch, Claudia Williams, and Robert Drago, "Pay Secrecy and Wage Discrimination" (report #Q016, Institute for Women's Policy Research, Washington, DC, 2011), http://www.iwpr.org/publicati ons/pubs/pay-secrecy-and-wage-discrimination.

Articles may be reprinted if Communities & Banking and the author are credited and the following disclaimer is used: "The views expressed are not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston or the Federal Reserve System. Information about organizations and upcoming events is strictly informational and not an endorsement."

About the Authors

About the Authors

Heidi Hartmann, Institute for Women's Policy Research

Elyse Shaw, Institute for Women's Policy Research