The Public Cost of Low-Wage Work in New England

Stagnating wages are causing many working families to end up on public assistance. More minimum-wage laws could change that scenario.

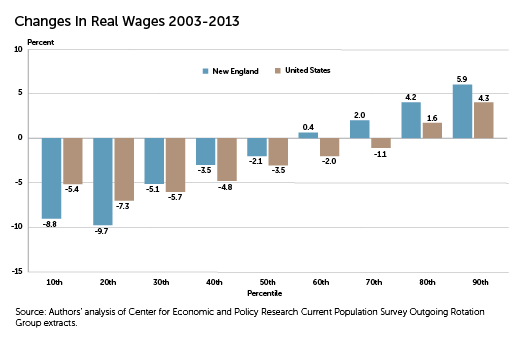

The decade 2003 to 2013 was a tough one for workers in the United States, 70 percent of whom saw their real (inflation-adjusted) wages decline. In New England, 50 percent of workers experienced a decline in real wages. Although that was less than workers nationwide, the changes were more extreme, with lower-wage workers experiencing deeper drops in their real wages and higher-wage earners making greater gains than in the nation as a whole.[1] (See "Change in Real Wages, 2003—2013.")

The decline in employer-provided health insurance has exacerbated the pain, with the share of nonelderly New Englanders who receive insurance from their employer falling from 72.3 percent in 2003 to 67.8 percent in 2013.[2] As job-based coverage has declined, more workers and their family members have enrolled in public health-care programs.

Stagnating wages and decreased employer benefits are a problem not only for low-wage workers, who increasingly cannot make ends meet, but also for state governments, which help finance the public safety net that many workers and their families must use.

State Dollars to Families

We examined the amount of state dollars that went to working families annually during the years 2009 to 2011 for two public benefit programs: health care (Medicaid and Children's Health Insurance Program, or CHIP) and basic household income assistance (Temporary Aid to Needy Families, or TANF).

Although costs for both programs are shared by the federal government and the states, we are reporting only the state portion here. Also, our analysis is just for the cash-assistance portion of TANF. We define working families as those that have at least one family member who works 27 or more weeks per year and 10 or more hours per week.[3]

Throughout the New England states, sizeable majorities of enrollees in Medicaid/CHIP were found to be members of working families. At the national level, working families made up 61 percent of Medicaid/CHIP enrollment. (See "Enrollment in Medicaid/Children's Health Insurance Program, 2009—2011.")

It is important to note that there have been significant changes in Medicaid enrollment since implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), but the data are not yet available. A key provision of the ACA expanded Medicaid coverage starting in 2014 to low-income adults under age 65, including those without children living at home, with the federal government paying 100 percent of the cost through 2016.

Thirty states and Washington, DC, have adopted the expanded Medicaid provision. That includes all the New England states except Maine. In addition, enrollment in traditional Medicaid—that is, among those who had been previously eligible—has also been boosted, in both expansion and nonexpansion states. That is the result of both the individual mandate to obtain health insurance and increased outreach, awareness, and system improvements to Medicaid related to the ACA—particularly since the opening of the health-care exchanges in October 2013. The costs will be shared by the federal government and the states as determined under traditional Medicaid formulas.

More than 90 percent of states' expenditures on Medicaid/CHIP and TANF went to Medicaid/CHIP, with TANF receiving a fraction of that amount. (See "Annual Cost for Medicaid/ Children's Health Insurance Program and Temporary Aid to Needy Families, 2009—2011.")

On average, 51 percent of New England states' public-assistance spending supported working families, essentially the same as the national average (52 percent). Collectively, the New England states spent $1.8 billion per year on public assistance to working families through the Medicaid/CHIP and TANF programs during the period 2009 to 2011.

Enrollment in Medicaid/Children's Health Insurance Program, 2009—2011

|

|

Enrollment of members of working families |

Percent of enrollment from members of working families |

|

Connecticut |

346,000 |

63% |

|

Maine |

147,000 |

59% |

|

Massachusetts |

770,000 |

61% |

|

New Hampshire |

94,000 |

72% |

|

Rhode Island |

90,000 |

56% |

|

Vermont |

100,000 |

66% |

|

New England |

1,547,000 |

62% |

|

United States |

34,100,000 |

61% |

| Source: Authors' calculations from 2010—2012 March Current Population Survey (CPS) and administrative data from the Medicaid and CHIP programs. Note: TANF enrollment data are not listed, because of sample size. |

||

Annual Cost for Medicaid/Children's Health Insurance Program and Temporary Aid to Needy Families, 2009—2011

|

|

Total state portion (2013 $ millions) |

Working family state portion (2013 $ million) |

Working family state share |

|

Connecticut |

$902 |

$486 |

54% |

|

Maine |

$140 |

$63 |

45% |

|

Massachusetts |

$1,965 |

$967 |

49% |

|

New Hampshire |

$160 |

$104 |

65% |

|

Rhode Island |

$199 |

$97 |

49% |

|

Vermont |

$160 |

$87 |

54% |

|

New England total |

$3,527 |

$1,805 |

51% |

|

United States total |

$48,400 |

$25,000 |

52% |

| Source: Authors' calculations from 2010 to 2012 March Current Population Survey and administrative data from Medicaid, CHIP, and TANF programs. | |||

Increasing Wages

When jobs don't pay enough, workers turn to public assistance in order to meet their basic needs. Such programs provide support to millions of working families. In fact, at both the state and federal levels, more than half of total spending on Medicaid/CHIP and TANF goes to working families. Given that reality, higher wages and increases in employer-provided health insurance would be expected to result in Medicaid savings. And in the case of TANF—a federal block grant that requires states to maintain a specified level of funding for programs directed to low-income families—higher wages would allow states to reduce the portion of program dollars going to cash assistance and consider increasing the funding for services such as child care, job training, and transportation assistance. Lowering public-assistance costs through higher wages and employer-provided health care should allow all levels of government to do a better job of targeting their tax dollars.

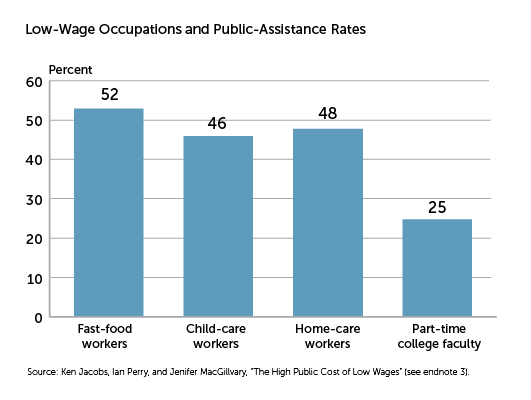

In 2014, Massachusetts committed to raising its minimum- wage to $11 by 2017, and in June 2015, the state's home-care workers won a $15-an-hour starting wage, to be provided by 2018. (See "Low-Wage Occupations and Public-Assistance Rates.") Vermont, Connecticut, and Rhode Island also recently passed minimum-wage increases. Maine will have a $12 minimum-wage proposal on the 2016 ballot, and Massachusetts lawmakers are pursuing legislation similar to New York State's requiring a $15 wage for fast-food workers and workers at big retail chains. Portland, Maine, joined a growing number of cities and counties across the country that are raising minimum wages at the local level. A $10.68 minimum wage passed in the Portland City Council, and as of this writing, a $15 minimum-wage referendum was on Portland's November ballot. Meanwhile, Connecticut legislators proposed in spring 2015 first-of-its-kind legislation that would have fined large corporations $1 an hour for each employee whose wages were lower than $15 an hour. The full bill did not pass, but it established an advisory council of workers and consumers to make recommendations on how the state can handle low-wage employment.

Currently, it appears to be left to state and local governments to address the declining real wages that workers, especially low-wage workers, have contended with over the past decade. Acting on the problem of low-wage work will help more than just the recipients of pay increases. Since the cost of low-wage work is borne widely, the benefits of wage increases are likely to be enjoyed widely.

Low-Wage Occupations and Public-Assistance Rates

Reliance on public assistance can be found among workers in a diverse range of occupations. Nationally, three of the recently analyzed occupations with particularly high levels of public-assistance program utilization are frontline fast-food workers, child-care providers, and home-care workers (mainly home health aides and personal-care aides). At or near 50 percent of each group's workforce is in families where at least one member is enrolled in one or more of Medicaid/CHIP, TANF, Earned Income Tax Credit, and SNAP (food stamps).

However, high reliance on public-assistance programs among workers isn't found only in service occupations. Fully one-quarter of part-time college faculty and their families also are enrolled in public-assistance programs.

Ken Jacobs is chair of the UC Berkeley Center for Labor Research and Education. Ian Perry is a graduate student at the UC Berkeley Goldman School of Public Policy. Jenifer MacGillvary is publications coordinator at the UC Berkeley Center for Labor Research and Education. Contact them at kjacobs9@berkeley.edu.

Endnotes

- Authors' analysis of Center for Economic and Policy Research Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group extracts. See ceprdata.org/cps-uniform-data-extracts.

- Integrated Public Use Microdata Series Current Population Survey (IPUMS-CPS), 2003—2013 March CPS, Minnesota Population Center, University of Minnesota, www.ipums.org.

- Ken Jacobs, Ian Perry, and Jenifer MacGillvary, "The High Public Cost of Low Wages" (research brief, UC Berkeley Center for Labor Research and Education, Berkeley, California, April 2015), http://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/pdf/2015/the-high-public-cost-of-low-wages.pdf. Funding for the research was provided by the Service Employees International Union.

Articles may be reprinted if Communities & Banking and the author are credited and the following disclaimer is used: "The views expressed are not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston or the Federal Reserve System. Information about organizations and upcoming events is strictly informational and not an endorsement."

About the Authors

About the Authors

Ken Jacobs, University of California-Berkeley

Ian Eve Perry, University of California-Berkeley

Jenifer MacGillvary, University of California-Berkeley