2017 Series • No. 17–2

Current Policy Perspectives

Relative Pay, Productivity, and Labor Supply

Concerns regarding relative pay—earnings compared with the earnings of others doing a similar job or compared with one's earnings in the past—affect labor supply and productivity. Specifically, changes in pay, transparency of differential pay across workers, and the ability to explain these differences seem to be important for the decision of how much to work and how much effort to exert on the job. This implies, in turn, that relative pay concerns may contribute to unemployment and help determine the success or failure of using differential pay to incentivize employees. This brief summarizes a collection of studies showing the effect of relative pay information, even if irrelevant, on labor supply and effort.

Key Findings

Key Findings

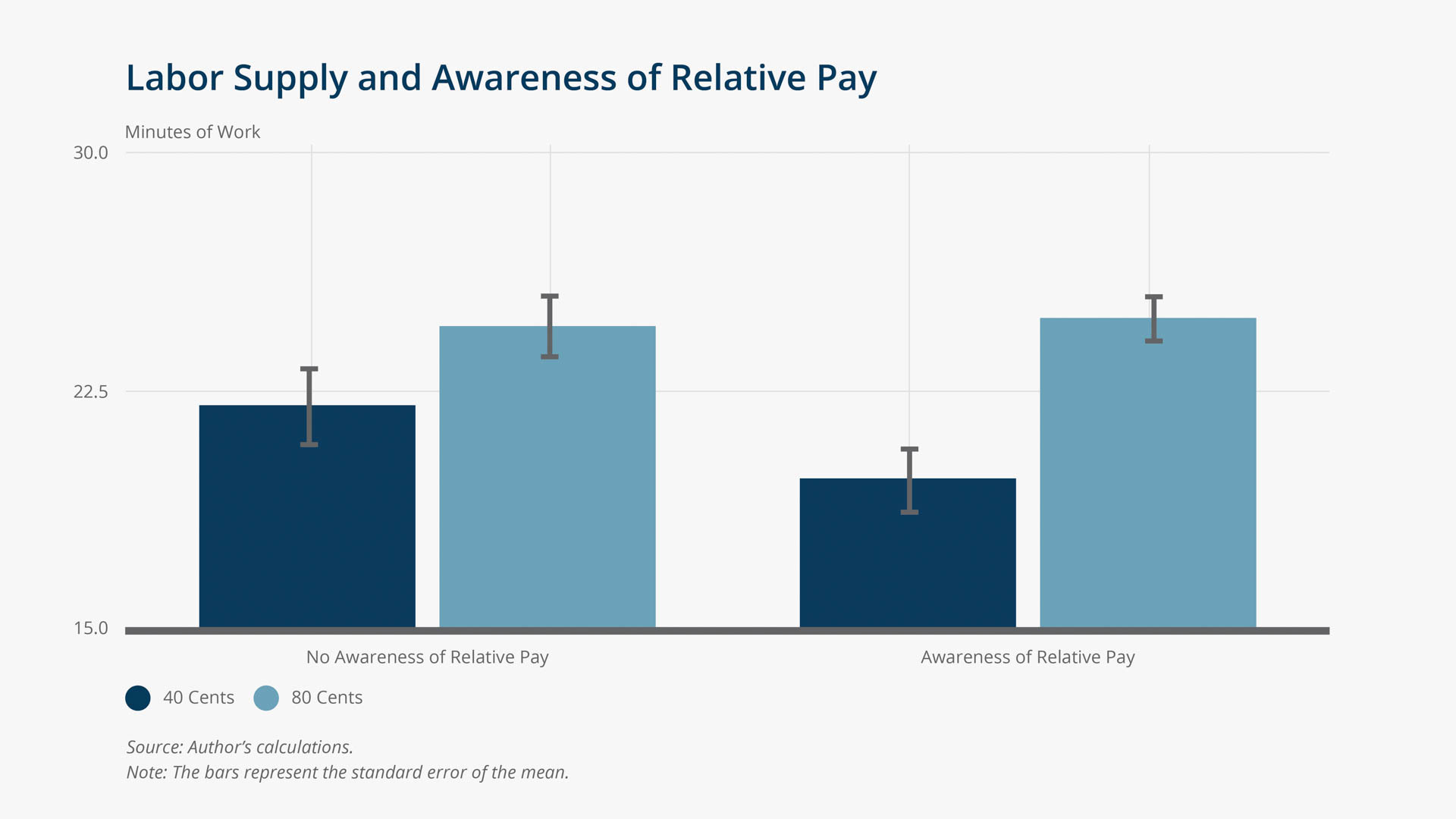

- Lab, field, and empirical work results show that relative pay does affect labor supply. Those who are compared unfavorably reduce their supply, while the labor supply of those who are unaffected or are compared favorably does not change.

- Relative pay also affects the amount of on-the-job effort. Here also, the effect is via the behavior of those whose relative pay compares unfavorably with others' or with their pay in the past.

- Differential productivities may serve as an acceptable explanation for differential pay, and intentions matter: when wage differentials were not picked by the employer, the negative effect of differential pay disappeared.

Exhibits

Exhibits

Implications

Implications

The potential negative effects of relative pay and the conditions under which they are found are clearly important to consider when designing workers' incentives, especially differential pay, and when thinking of unemployment in time of recession. One of the conditions that matters is the workers' awareness and/or the reason for the relative pay. Workers seem to accept lower relative pay when there is even a weak acceptable explanation for it.

Relative pay also has implications for unemployment, as past pay has been shown to affect labor supply. During the Great Recession, for instance, a majority of job loss was concentrated in the construction industry, where the weekly wage is higher than in industries to which the unemployed could likely switch, such as transportation and hospitality. Although this idea demands further research, relative pay may be part of the explanation of the prolonged unemployment spells workers experienced. Likewise, differential pay across workers may also be a factor in reducing labor supply and may also contribute to unemployment. Unlike the effect of current pay relative to past pay, the effect of differential pay on unemployment may depend on the observability of pay across workers and the extent of the difference across employees (wage compression).

Abstract

Abstract

Relative pay—earnings compared with the earnings of others doing a similar job, or compared with one's earnings in the past—affects how much individuals would like to work (labor supply) and their effort on the job; it therefore has implications for both employers and policy makers. A collection of recent studies shows that relative pay information, even when it is irrelevant, significantly affects labor supply and effort. This effect stems mainly from those who compare unfavorably, as essentially all studies find that awareness of earning less than others or less than in the past significantly reduces labor supply or effort on the job. Comparing favorably, however, has mixed effects. For labor supply, awareness of pay differences either has a positive effect, when the comparison is with past pay, or no effect, when the comparison is with others' pay, and it generally has no effect on exertion of effort.