Credit Card Utilization and Consumption over the Life Cycle and Business Cycle

Nearly 80 percent of U.S. adults have a credit card, and more than half of them revolve their debt from month to month. Using a large sample of credit bureau data, this paper documents a tight link between available credit (the limit) and credit card debt, and then it offers a model-based interpretation of this linkage. Credit limits change frequently for individuals, increase rapidly on average as people age, and show large changes over the business cycle. Yet credit card debt changes nearly proportionately to credit and at about the same time, so the fraction of credit used is relatively stable over time. The authors build a life-cycle consumption model that includes the joint use of credit cards to pay directly for expenditures, to help smooth consumption against income shocks, and to borrow longer term (revolving indefinitely). The authors estimate the parameters of the model using several data sources, including a large credit bureau database and a new daily diary of consumer payment choices.

Key Findings

Key Findings

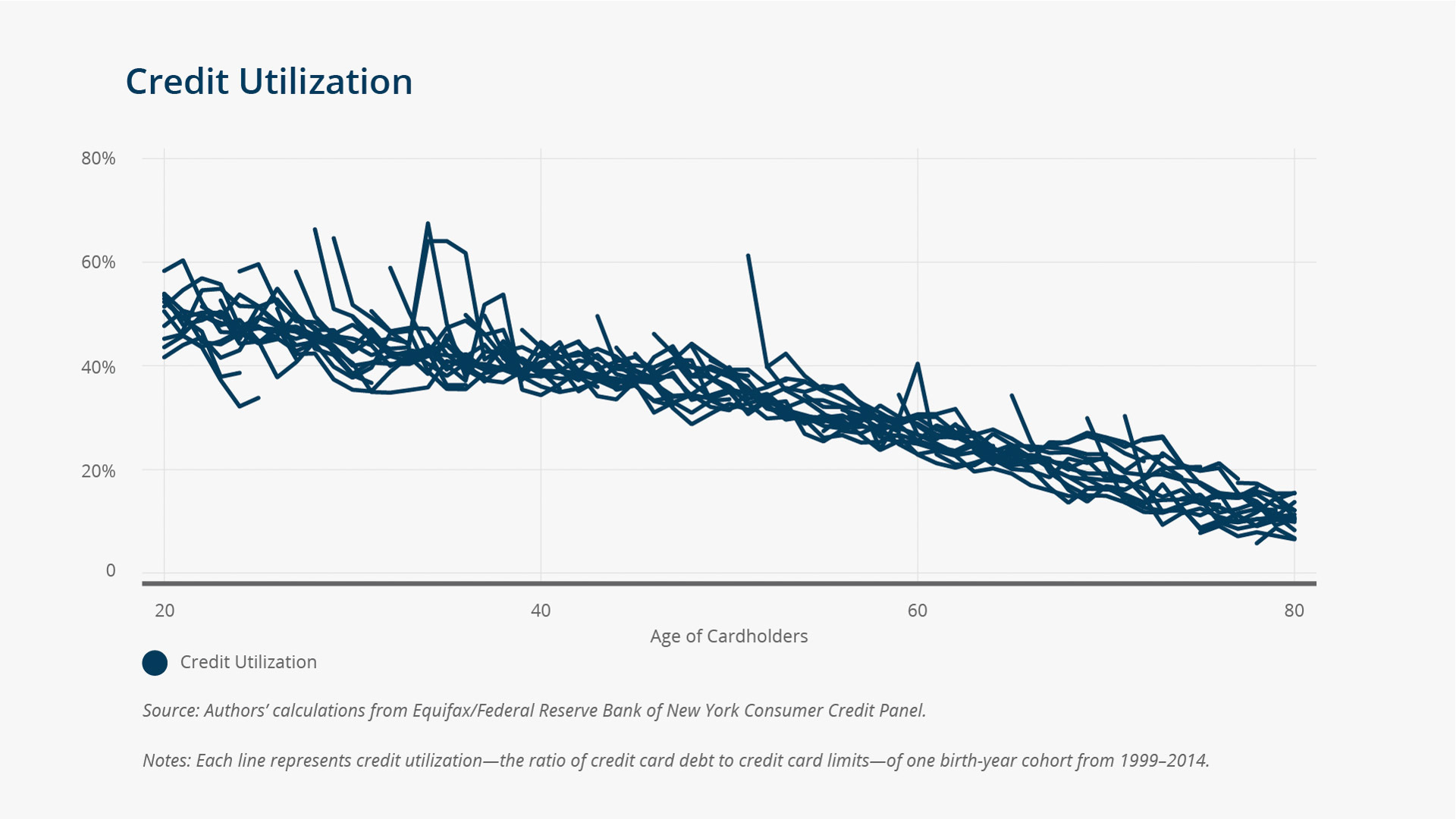

- During the 2008–2009 financial crisis, the average credit card limit fell by about 40 percent, reducing total available credit by nearly a trillion dollars. At the same time, Americans reduced their credit card debt by a similar amount, and so the average credit utilization—the fraction of available credit used—was nearly constant from 2000–2015.

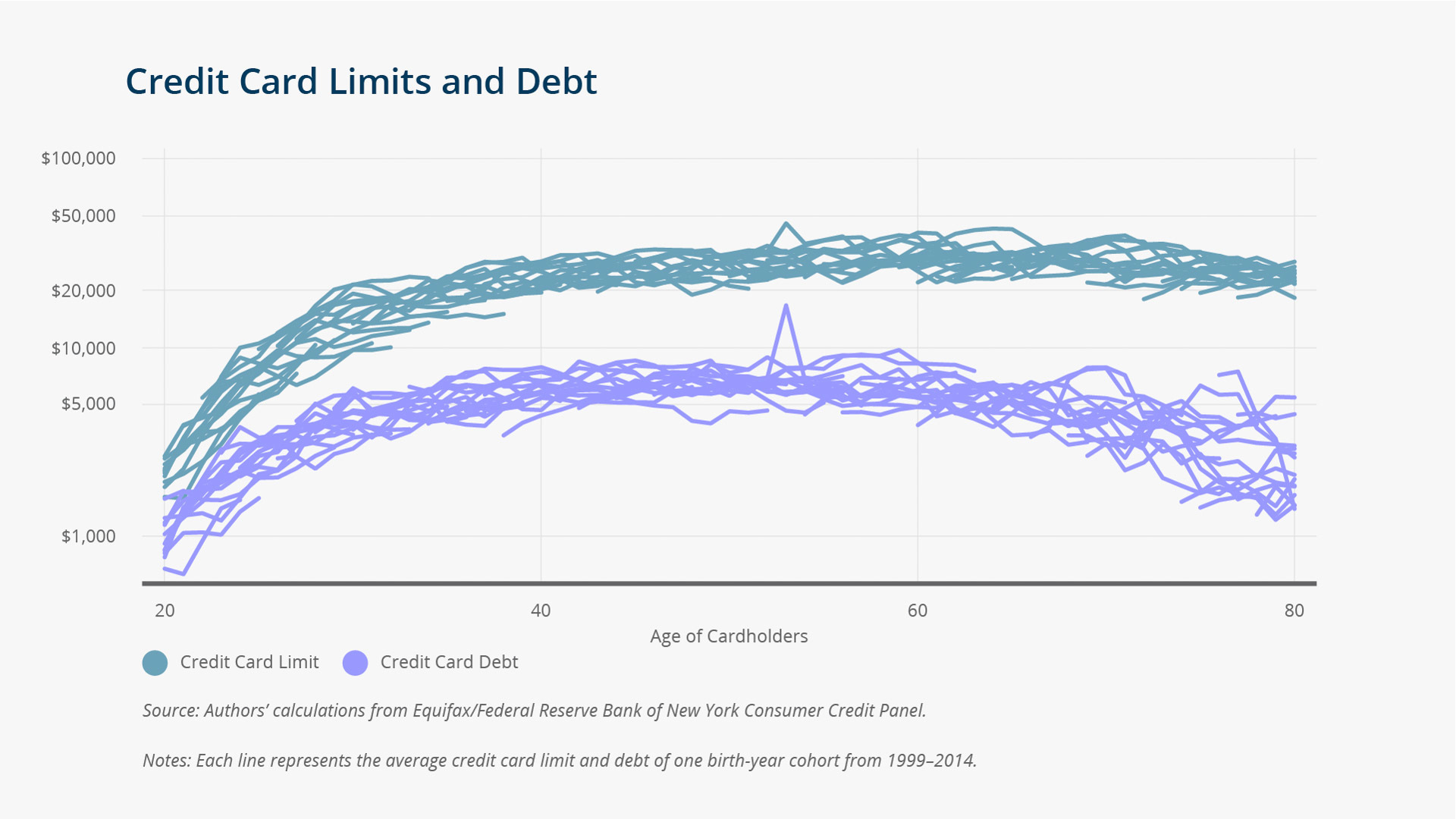

- On average, a person’s credit increases by about 700 percent from ages 20 to 40 and then continues to increase at a much slower rate. Credit card debt increases at nearly the same rate, and so the average cardholder is using around half of his or her available credit from ages 20 to 50.

- The authors estimate that the convenience value of using credit cards for consumer payments is around $40 billion a year. Using the Diary of Consumer Payment Choice, they estimate that a convenience user—someone who is not revolving debt—spends 18.2 percent on average on a credit card. Revolvers spend only 15.6 percent. Because revolvers must pay interest on purchases immediately, this difference in revealed preference provides a unique form of identification to estimate the value of credit cards for payments.

- Incorporating all the uses for credit cards into the structural model, the authors estimate that more than half of the population must be quite impatient, prioritizing spending today over saving for tomorrow. The key intuition behind this result is that the willingness to borrow at 14 percent interest, except to smooth over an occasional shock, shows a large willingness to spend today at the expense of the future.

- Impatient people are generally living close to hand to mouth, and so their consumption and income move together closely over time. The authors’ structural estimates help explain the puzzle of why the response to tax rebates is so large (Parker et al. 2013, Kaplan and Violante 2014).

- The authors’ model estimates predict the slow fall in credit utilization over the lifecycle and the stability of credit utilization over the business cycle, and they match the individual relationship between credit and debt closely. However, the model does not explain why some revolvers switch to convenience use of credit cards later in life.

Exhibits

Exhibits

Implications

Implications

People experience important changes in credit throughout their life, especially between the ages of 20 and 40, when their credit limits soar. These changes in credit are in effect changes in liquidity, and observing how people react to them provides insight into the more general savings and consumption decisions they make.

Although people use credit cards for different purposes, all uses contribute to stable credit utilization. Payment use is proportional to consumption, and when an increase in income leads to an increase in credit limits, a convenience user will increase consumption and payments use. People who use credit cards to borrow because of impatience see a rise in their credit limit as an increase in wealth and increase their consumption (and debt) accordingly. And those who use credit cards for smoothing purposes early in life—when income rises more slowly than credit limits—increase their credit card debt at about the same rate as their credit limits rise.

Abstract

Abstract

The revolving credit available to consumers changes substantially over the business cycle, life cycle, and for individuals. We show that debt changes at the same time as credit, so credit utilization is remarkably stable. From ages 20–40, for example, credit card limits grow by more than 700 percent, and yet utilization holds steadily at around 50 percent. We estimate a structural model of life-cycle consumption and credit use in which credit cards can be used for payments, precautionary smoothing, and life-cycle smoothing, uniting their monetary and revolving credit functions. Our estimates predict stable utilization closely matching the individual, life-cycle, and business-cycle relationships between credit and debt. The preference heterogeneity implied by the different uses of credit cards drives our results. The revealed preference that some people with credit cards borrow at high interest, while others do not, suggests that around half the population is living nearly hand to mouth.