Mortgage-Default Research and the Recent Foreclosure Crisis

This paper reviews how previous and contemporary mortgage-default research informed—or, in some cases, should have informed–policy discussions during the foreclosure crisis. It also evaluates default behavior during the crisis in light of previous findings, and it discusses the new research questions and opportunities that the crisis has created.

The authors note that all theories of default imply that negative equity is a necessary condition for default, because borrowers with positive equity can avoid default by selling their homes and pocketing what’s left over after paying off their mortgages. But different theories of default are less concrete about what a homeowner should do once equity becomes negative. Arbitrage-based models grounded in formal theories of household optimization imply that default depends only on aggregate factors such as house prices and interest rates, not on the individual characteristics or circumstances of the borrower. Conversely, so-called double-trigger models allow adverse life events such as job loss and illness to precipitate defaults. Double-trigger models generate more-realistic empirical predictions, but they are less grounded in formal household optimization. This paper discusses how the foreclosure crisis has encouraged economists to blend these two extremes into a third alternative that provides an optimizing foundation for the default function and formalizes the previously ad hoc approach of double-trigger models.

A substantially revised version of this paper has been published as: “Mortgage-Default Research and the Recent Foreclosure Crisis,” 2018, Annual Review of Financial Economics 10: 59–100. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-financial-110217-022541

Key Findings

Key Findings

- Once U.S. house prices fell in the late 2000s, the foreclosure crisis proceeded pretty much as empirical mortgage researchers expected. The failure to predict the crisis stemmed from analysts’ inability to foresee the massive fall in house prices–a failure that concerns the science of asset pricing, not the study of how mortgage defaults relate to asset prices (such as house prices).

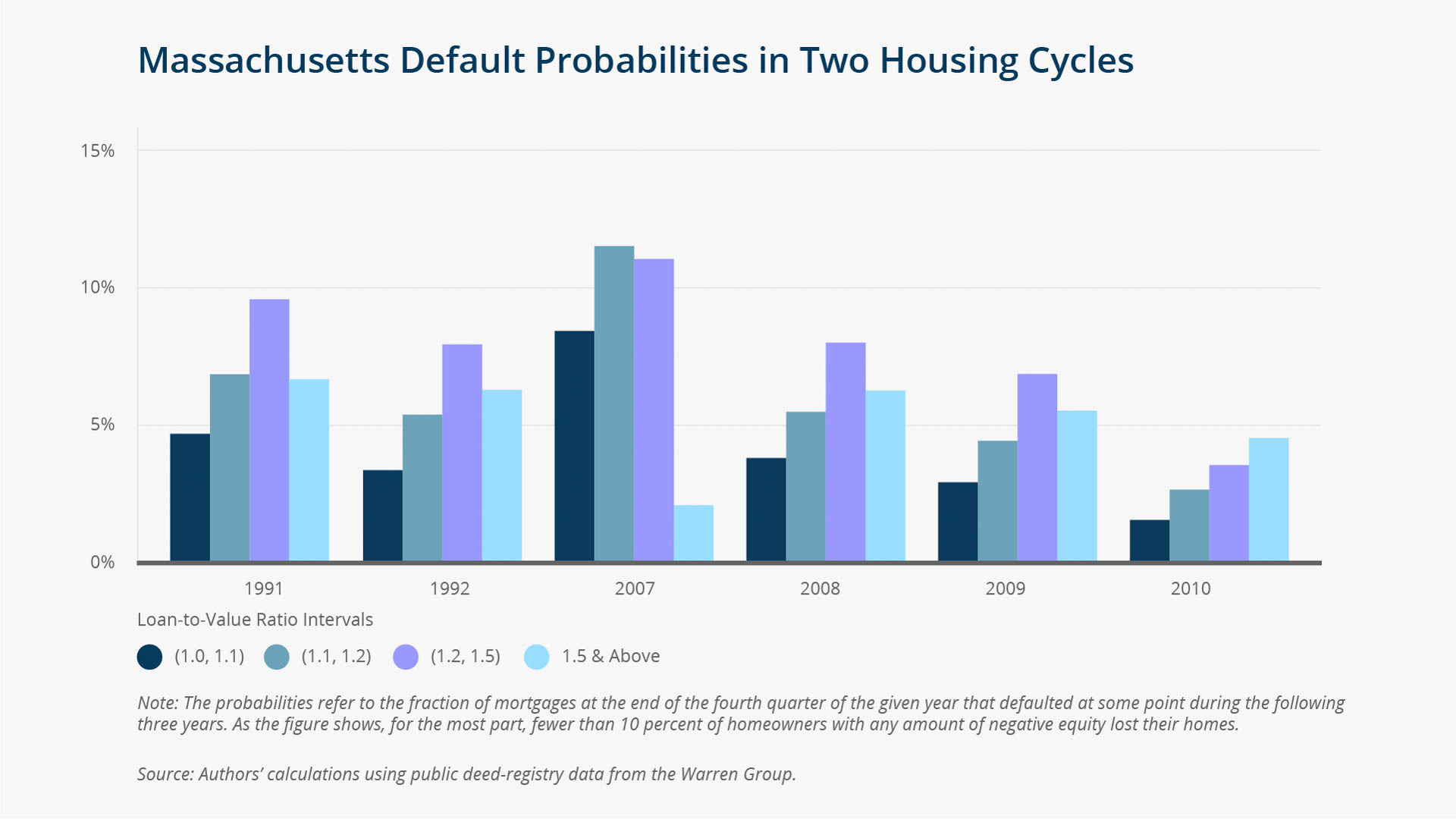

- Even though defaults rose markedly during the crisis, in general default is surprisingly rare. People with very deep negative equity do not walk away from their homes as often as theory would predict, and even financially stressed borrowers display a strong aversion to default. Had people defaulted as much as theories predict, the recent foreclosure crisis would have been worse.

Exhibits

Exhibits

Implications

Implications

From researchers’ perspective, the foreclosure crisis had a silver lining. The large loan-level datasets traditionally used in default research are now more widely available, and new datasets have been developed. Research on defaults was advanced theoretically and empirically by the time the crisis began, but economists have moved the frontier further by improving data sources, building dynamic optimizing models of default, and explicitly addressing reverse causality between rising foreclosures and falling house prices.

Going forward, improvements to data and models will allow researchers to explore the question of why mortgage default is so rare, even for households with high levels of negative equity or financial distress. But homeowners may already have the answer: price busts are temporary. Owners avoid default after housing busts because they expect the restoration of positive equity within a few years. Comprehensive models of mortgage default may have to account for this phenomenon, despite the difficulty of modelling mean reversion in asset prices.

Abstract

Abstract

This paper reviews recent research on mortgage default, focusing on the relationship of this research to the recent foreclosure crisis. Research on defaults was advanced both theoretically and empirically by the time the crisis began, but economists have moved the frontier further by improving data sources, building dynamic optimizing models of default, and explicitly addressing reverse causality between rising foreclosures and falling house prices. Mortgage defaults were also a key component of early research that pointed to subprime and other privately securitized mortgages as fundamental drivers of the housing boom, although this research has been criticized recently. Going forward, improvements to data and models will allow researchers to explore the central unsolved question in this area: why mortgage default is so rare, even for households with high levels of negative equity or financial distress.