The Dollar During the Global Recession: US Monetary Policy and the Exorbitant Duty

Since the US dollar is the world’s dominant currency, the United States benefits from the “exorbitant privilege” of paying low interest rates on safe (risk-free) dollar-denominated assets, such as the bonds issued by the US government. When global risk aversion is elevated, investors tend to hedge against uncertainty by switching to dollar-denominated assets, a form of insurance termed the “exorbitant duty” that comes with serving as the world’s reserve currency.

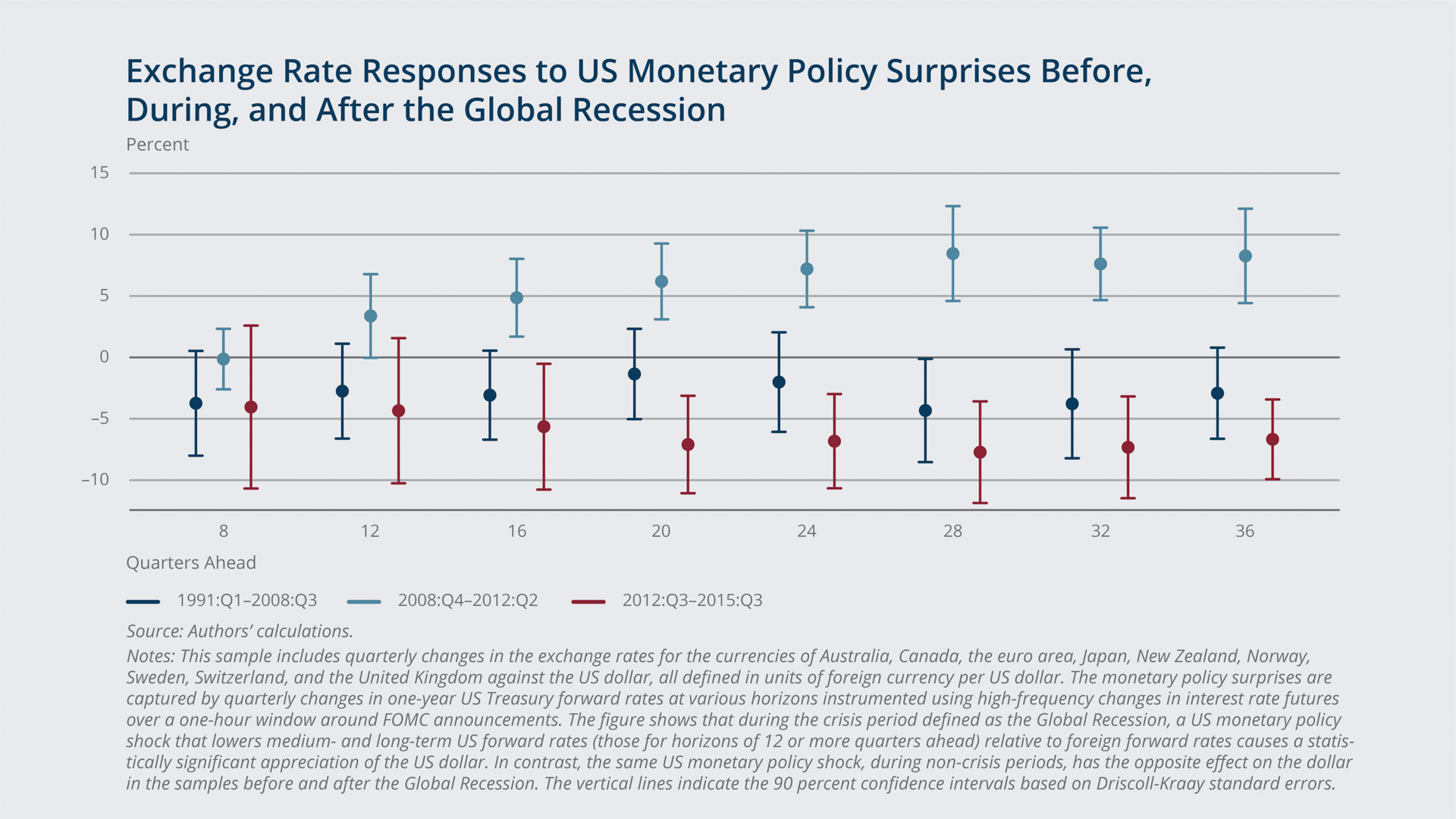

While the international macroeconomics literature has a clear understanding of the flight-to-safety effects imposed upon the United States during crises, it provides no answers about what types of exogenous shocks trigger the dollar’s exorbitant duty behavior and by what channels these shocks are transmitted. The authors study how the US dollar responded to the Fed’s monetary policy actions during the Global Recession, defined as 2008:Q4 through 2012:Q2, and find that Fed easings during this period actually led the dollar to appreciate, thus triggering its “exorbitant duty” in a way that runs counter to conventional wisdom. The authors use a novel decomposition of the exchange rate response to study the channels that led to this appreciation and propose a theoretical model that reconciles and explains these novel findings.

Key Findings

Key Findings

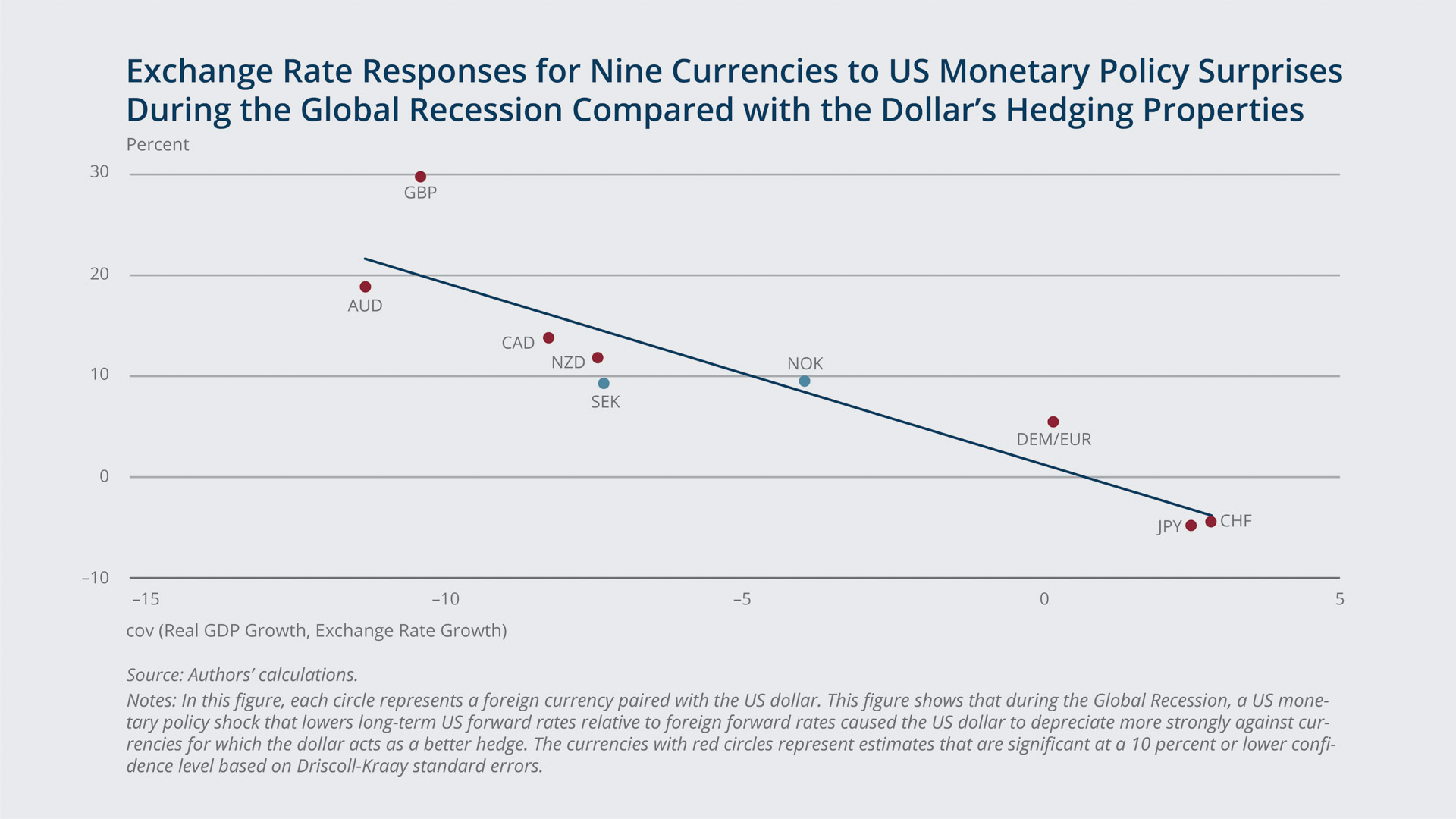

- Contrary to the accepted wisdom which predicts that cutting US interest rates will cause the dollar to depreciate, the authors show that the US dollar significantly appreciated in response to the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy easing(s) over the course of the Global Recession. Furthermore, the currencies for which the dollar serves as a hedge are those that lost the most value against the dollar in response to accommodative monetary policies enacted during the Global Recession.

- One channel that caused this appreciation was a flight-to-safety effect manifested in the currency risk premium component of exchange rate changes. Across currencies, those for which the dollar serves as a hedge are the ones that lost the most value against the dollar through this flight-to-safety effect in response to Fed easings. These differences in effects across currencies underpins the cross-currency heterogeneity in the overall dollar appreciation. As a source of this flight-to-safety effect, the authors show that a US monetary policy easing that lowered US forward rates by 1 percentage point led to an increase in estimated investor risk aversion of between 28 and 43 percent during the Global Recession.

- The second main channel pushing the dollar to appreciate was that Fed easings lowered the expected future path of US inflation relative to other countries.

- Another aspect of the dollar’s “exorbitant duty” that was triggered by these Fed easings is the transfer of financial wealth from the United States to the rest of the world. A US monetary policy easing that lowered US forward rates by 1 percentage point led to a significant decline of US net foreign asset positions worth up to 18 percent of US GDP. The part of the resulting loss due to changes in asset valuations alone was high as 17 percent of US GDP.

- All the empirical findings can be explained by a theory in which calendar-based forward guidance during this period, the Fed’s monetary policy that was intended to be accommodative, had conveyed a strong signal that future US GDP growth would be lower than economic agents previously expected. A US monetary policy easing that lowered US forward rates by 1 percentage point also caused a downward revision of US GDP growth expectations of between 0.71 and 1.03 percentage points.

The effects of this signaling channel overshadowed the direct expansionary effect the Fed intended when promising that policy rates would remain low for the foreseeable future. The theory predicts that this signaling channel dominates when economic agents have more uncertainty about economic fundamentals relative to uncertainty about monetary policy, and when policy is conducted in a way that leaves these actions potentially open to being interpreted as signals about the central bank’s true sense of the economy. The paper argues that both conditions were met during the Global Recession.

Exhibits

Exhibits

Implications

Implications

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first paper to show that accommodative monetary policy can trigger the exorbitant duty behavior of the US dollar. The Federal Reserve’s historically unprecedented accommodative monetary policy measures enacted during the Global Recession prompted other countries to complain that the United States was engaging in “currency wars” and “competitive devaluations,” as Ben Bernanke, who chaired the Fed during this crisis period, recounted in a 2017 paper, “Federal Reserve Policy in an International Context.” The surprising evidence that the signaling channel of monetary policy can be dominant enough to prevail over the direct effect of interest rate movements challenges this ingrained acceptance that interest rate cuts should cause the home currency’s value to fall.

Moreover, the authors find that US monetary policy may play an important role in triggering sizable wealth transfers between the United States and the rest of the world. Taken as a whole, the empirical and theoretical evidence presented in this paper poses a challenge to the vast majority of open economy models used to study exchange rates and monetary policy, as these models do not allow for the possibility that monetary policy easings may convey signals that can cause the home currency to appreciate. As a result, conclusions about the international spillover effects of policy actions taken during a crisis, such as the recent Global Recession, may be severely flawed.

Abstract

Abstract

We document that during the Global Recession, US monetary policy easings triggered the “exorbitant duty” of the United States, the issuer of the world’s dominant currency, by causing a dollar appreciation and a transfer of wealth from the United States to the rest of the world. This dollar appreciation runs counter to the predictions of standard macroeconomic models and works through two channels: (i) a flight-to-safety effect which lowered the expected excess returns of holding safe US government debt relative to foreign debt and (ii) lowered expected future inflation in the United States relative to other countries. We show that the signaling channel of monetary policy, whereby US policy easings are perceived to signal weaker future growth, can reconcile the novel empirical findings that we document.