Inflation Thresholds and Inattention

Inflation expectations—which are a gauge of how much economic agents anticipate prices will change in the near future—help determine the level of economic activity. The classic Phillips curve relationship first developed in the late 1950s contends that unemployment rates lower than the NAIRU (nonaccelerating inflation rate of unemployment) risk driving up the price level via higher inflation. Yet two very recent studies by Coibion and Gorodnichenko (2018) and Doser et al. (2018) have shown that incorporating consumer inflation expectations, as measured by the University of Michigan’s Survey of Consumers (MSC), can explain why the Phillips curve relationship seems to have become flatter over the past two decades. They show that after accounting for consumer inflation expectations, the inflation-employment relationship appears stable, and the well-anchoring of these expectations also explains why there was no disinflation (negative inflation) during the Great Recession.

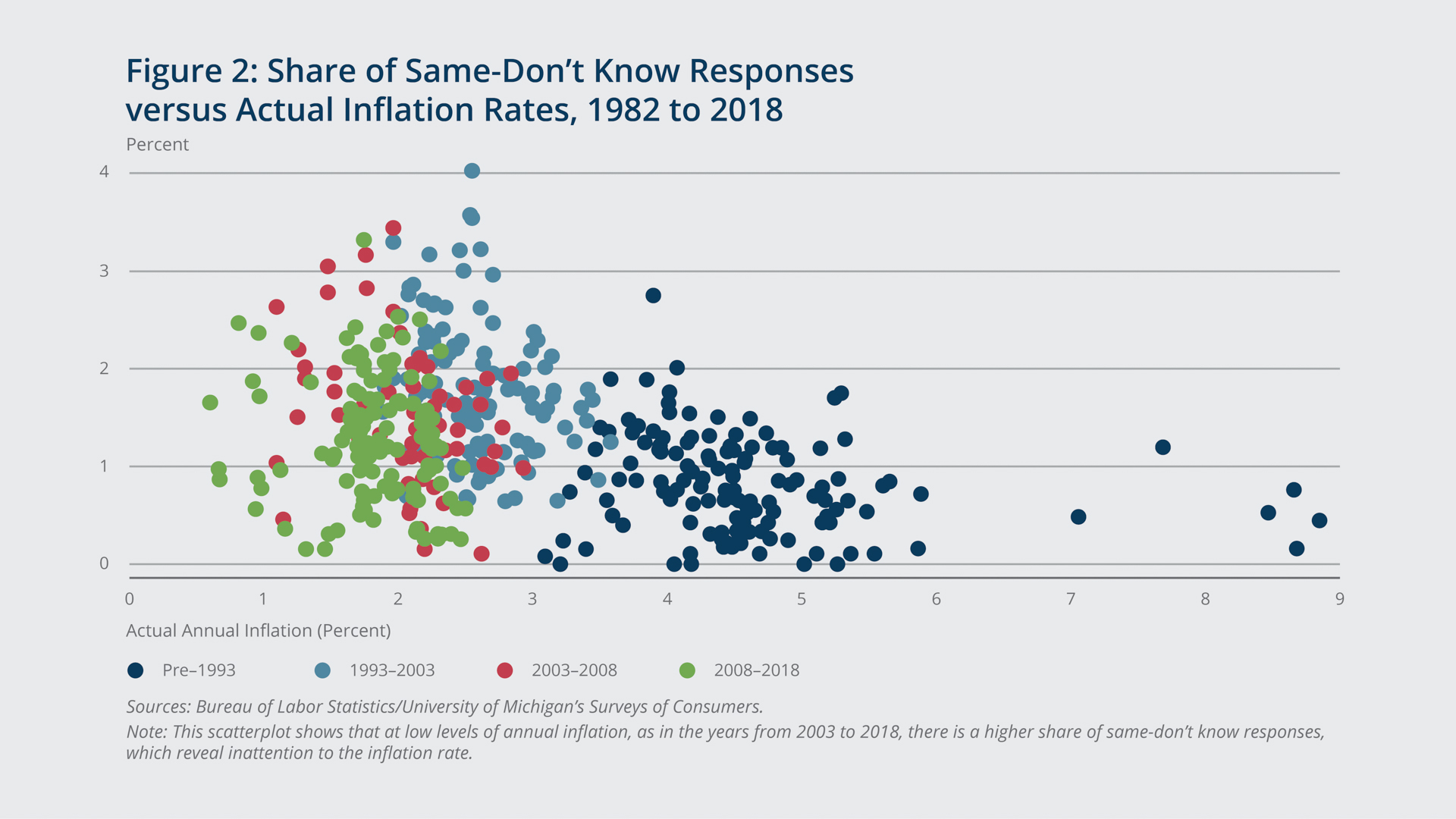

Many theories, such as full information rational expectations and adaptive expectations (learning from past experience), have been offered to account for how consumers shape their expectations about future inflation. Another hypothesis is the idea of inattention. Yet in the context of consumers’ inflation expectations, direct empirical evidence documenting the extent of inattention over a long period of time in the United States is very scarce: Coibion, Gorodnichenko, and Kumar (2018) find evidence of inattention based on firm-level data, while Cavallo, Cruces, and Perez-Truglia (2017) present experimental evidence comparing consumer attention to inflation at one given point in time in countries that have experienced bouts of high or low inflation. In order to judge how well consumers form one-year ahead inflation expectations, the authors exploit information obtained from the MSC to construct three direct measures of inattention to current inflation. The first measure is novel to the literature, as it captures respondents initially predicting that prices will go up over the next 12 months at the same annual inflation rate as the current one, then upon probing further, they reveal that they actually do not know what the current inflation rate is. These “Same-Don’t Know” (Same-DK) responses are analyzed using MSC data spanning several decades, thus capturing a range of different US macroeconomic conditions.

Key Findings

Key Findings

- A higher share of Same-DK responses are observed at low levels of inflation, defined as being below a threshold level that is between 2 and 4 percent annually. When inflation rates are above 4 percent, there are many fewer instances of Same-DK responses, smaller scaled errors in forecasting, and a greater correction to account for past mistakes in forecasting.

- There is a negative and statistically significant relationship between the past overestimates in forecasts and median inflation expectations during high-inflation regimes, but not during low-inflation regimes. This indicates that individuals pay more attention to inflation and update their future inflation expectations more in light of new information about inflation when inflation is beyond a certain threshold.

- A similar pattern of results occurs when the analysis omits the last 15 years, 2003 through 2018, a period characterized by very low inflation and well-anchored long-run expectations. A test for whether these responses were conditioned on the respondents having lived through a period of high inflation during their prime suggests that the behavioral pattern documented in this paper is not driven by a specific cohort.

- The pattern of Same-DK responses and low inflation rates suggests that the inflation-employment relationship may have been flatter during earlier periods of low inflation, not just in low inflation periods that have occurred during the past 20 years.The authors plot annual inflation measured by the Consumer Price Index against the unemployment rate for the low inflation period between 1958 and 1969, and show that the Phillips curve is flatter when annual inflation is under 3 percent. However, between 1970 and 1994 there were several periods of high inflation, and the classic Phillips curve relationship of high inflation being correlated with low unemployment re-emerged, which cautions against complacency that high inflation could not return at some point.

Exhibits

Exhibits

Implications

Implications

Regardless of what proxy measure for inattention is used, the results consistently show that consumer inflation expectations are insensitive to actual inflation when the annual inflation rate is below 2–4 percent. One implication of this finding is that despite the US unemployment rate being at a 50-year low, the risk of higher inflation seems to be limited since the current annual inflation rate is around only 2 percent. This also means that consumption and wage negotiations should be less affected by current economic conditions, which will also reduce inflation pressure. This implication is underscored by previous studies which have shown that the MSC inflation expectations have provided the best explanation of realized inflation, both before and after the Great Recession, and other studies which have shown that consumers’ inflation expectations may reflect firms’ inflation expectations.

From a behavioral perspective, insensitivity to the annual inflation rate when it is low conforms to what psychologists call Weber’s Law, which centers around a concept termed a “just noticeable difference.” The idea is that humans sense change above some threshold level, which proportional to the initial stimuli. Applying this insight to inflation expectations implies that consumers are insensitive to small changes in prices up to a certain level, which these findings suggest is around 4 percent annual inflation. While previous studies have found mixed results for the just noticeable difference when applied to inflation expectations, the findings in this paper suggest that further work using this concept might yield more insight into how inflation expectations are formed.

Abstract

Abstract

Inflation expectations are key to economic activity, and in the current economic climate of a heated labor market, they are central to the policy debate. At the same time, a growing literature on inattention suggests that individuals, and therefore individual behavior, may not be sensitive to changes in inflation when it is low. This paper explores evidence of such inattention by constructing three different measures based on the University of Michigan’s Survey of Consumers 1-year ahead inflation expectations. Exploring inflation thresholds of 2, 3, and 4 percent, our findings are consistent with the inattention hypothesis.