Walkable and Affordable Communities

Lower transportation costs, improved health, and other societal benefits can offset lowered affordability in communities where improved walkability has raised housing values.

Throughout history, cities and towns have been built upon residents' ability to access employment, services, and friends-on foot. But after WW II, the automobile and a suburban housing boom changed all that. The middle class left city centers. Lower-income populations remained.

Today we are seeing an urban resurgence, with walkable centers in demand. That makes city centers less affordable. But a view of affordability that includes both transportation and housing can help communities plan for a mix of uses and can enable residents of all income levels to develop more healthful lifestyles.

Benefits and Challenges

Walking is an accessible and free intervention to increase physical activity and health. The website WalkWithADoc.org lists 100 benefits of walking, including managing Type 2 diabetes, reducing blood pressure and weight, and improving psychological functioning. Walkable communities provide benefits for people of all ages and capacities while they do errands, go to school or work, and visit friends. And considering that many people do not drive, the sidewalk may be the ultimate public space. (See "Revere Embraces Walking.")

Walkable town centers are becoming a preference for young adults, seniors, and growing numbers of homebuyers. The shift in attitude has led to premium pricing in walkable districts.[1] That has caused some residents to worry about gentrification, higher rents, and real estate values that drive up taxes.

One way to alleviate the increasing housing burden is to lower the cost of transportation, the second-largest expense for American households after housing. Low- and moderate-income households-including rural households-spend up to 42 percent of their total annual income on transportation. Even middle-income households spend almost 22 percent of their income on transportation.[2]

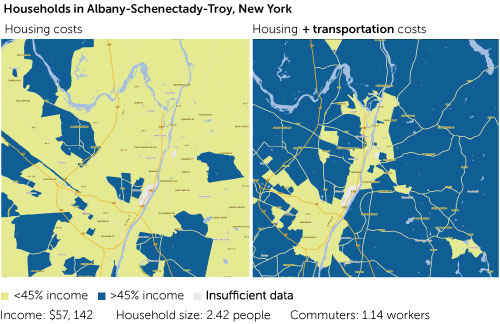

Traditionally, housing affordability has been defined as no more than 30 percent of income spent on housing. But as the website H+T Affordability Index suggests, 45 percent for housing and transportation, combined, may be a better measure.[3] Household transportation costs can be slashed if jobs and other key activities are accessible on public transit and if families reduce automobile use. (See "Share of Income Spent on Housing and Transportation, 2014.")

Analyzing Housing and Transportation Affordability

Three publicly available tools can help with understanding the links between walkability and housing/transportation affordability:

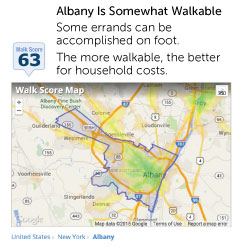

- Walk Score is a proxy for walkability, effectively measuring the proximity of services to homes;

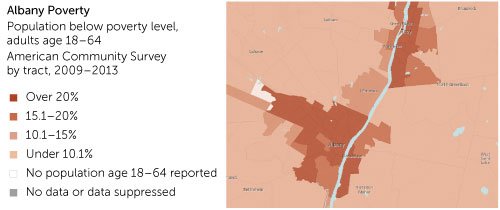

Community Commons provides maps with income and other demographics; and - H+T Affordability Index measures the affordability of housing alone and housing combined with transportation.

Albany, New York, has some central neighborhoods that are particularly low income, including areas where more than 30 percent of the people live in poverty. These areas overlap with areas that rank the most walkable according to the Walk Score website. Overlaid with the H+T analysis, the areas consistently stay within the 45 percent H+T measure.

The analysis helps demonstrate how walkability, income, and affordability are linked and suggests that location efficiencies can increase affordability and accessibility.

Other places boast similar scenarios. Walk Score recently published a list of cities that offer both walkability and affordable neighborhoods.[4] Among them are Buffalo and Rochester in New York. Providence and Philadelphia were relegated to runners up only because of their overall high average cost of living.

Making Walkability Work for Low-Income Areas

Although many low-income neighborhoods are affordable, it's important for cities to ensure that they are good places to live.

Safety

Automobiles contribute to the high percentage of fatalities and injuries in low-income areas. According to Governing magazine, poorer areas have approximately double the auto fatality rates of wealthier communities.[5] A report from Bridging the Gap, a program of the health-oriented Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, found that "low-income communities are less likely to encounter sidewalks, street/sidewalk lighting, marked crosswalks and traffic-calming measures such as pedestrian-friendly medians, traffic islands, curb extensions, and traffic circles."[6] Fortunately, solutions exist.

Crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED) is a multidisciplinary approach to improving safety and deterring criminal behavior. CPTED principles of design affect elements of the built environment ranging from the small scale (such as strategic use of shrubbery and other vegetation) to the overarching (such as an entire urban neighborhood's form and the level of opportunity for eyes on the street).

Roadway policy and environmental design. State and local governments can make it easier and safer for residents to walk in communities by adopting best practices for street design, implementing comprehensive zoning and community plans, and linking funding for capital improvements to best practices.

Housing and Transportation Assistance

Cities that increase and maintain affordable housing and transportation options help ensure that people in all economic sectors can remain.

Special public-interest zoning districts can be effective in providing affordable housing coupled with mixed-use development. In such zones, access to transit, parks, healthful food, and low-cost recreation are prioritized.[7]

Inclusionary zoning refers to municipal and county planning ordinances that require a given share of new construction to be affordable for low- and moderate-income people. In practice, these policies involve placing deed restrictions on 10 percent to 30 percent of new houses or apartments.

Ladders of Opportunity is a federal program that makes competitive-grant funds available through the Federal Transit Administration. The funds may be used to modernize and expand bus service specifically for the purpose of connecting disadvantaged and low-income individuals, veterans, seniors, youths, and others to workforce training, employment centers, health care, and other vital services.[8]

Baby boomers and their children comprise half the U.S. population. Recent data show that many prefer homes and commercial space in walkable neighborhoods, which do not exist in sufficient quantity.[9] Municipalities should ensure that zoning and development policies allow for new, more-intensive developments, including accessory dwelling units, which can provide lower-cost, smaller housing units for grandparents and others. Eliminating parking minimums also can help, by reducing the cost of development.

Communities are changing to become safer and more comfortable for all people to walk for daily needs and recreation. The shift is expected to yield massive benefits in health, economic prosperity, community, and traffic safety-even happiness. New England is well-positioned to capitalize on the trends as many communities are in close proximity to one another, have public transit infrastructure, and boast considerable historic platting on a walkable scale. Change generally starts with cities, including aging industrial cities and smaller towns, which could boost revitalization by focusing on their main streets and their access to transit.

In the process of improving walkability, however, it is critical for communities to develop in a way that maintains affordability for all. Ensuring that services and employment are within safe walking distance and instituting inclusionary zoning and similar policies are means of ensuring economic equity.

Scott Bricker is the director of America Walks, based in Portland, Oregon. Contact him at sbricker@americawalks.com.

Revere Embraces Walking

Brendan Kearney of WalkBoston points to Revere, a city north of Boston, as a lower-income community that values walkability. His organization dedicates one staff member to working with the Revere community.

Recent survey data show a shift to walking for students across all middle schools. A "Revere on the Move" campaign celebrates the progress so far and continues work on creating a healthier community through convenient access to physical activity and through environmental design. In 2013, the city was recognized by the Massachusetts Public Health Association as a leader in Healthy Community Design. It created its first urban trail in October 2011. In 2013, it installed a bike lane and celebrated a second urban trail. Also of note: a new 5-kilometer race, and hundreds of residents participating in the Citywide Fitness Challenge.

Although Revere was still lagging the surrounding cities as of fall 2014 in terms of its walk score (Chelsea, 79; Everett, 88; Lynn, 65; East Boston, 81; and Winthrop, 56), it had moved up to 60 ("average" walkability).

Endnotes

- See Gary Pivo and Jeffrey D. Fisher, "The Walkability Premium in Commercial Real Estate Investment," www.u.arizona.edu/~gpivo/Walkability%20Paper%20February%2010.pdf. The authors find that "the benefits of greater walkability were capitalized into higher office, retail, and apartment values" and that, on a "100 point scale, a 10 point increase in walkability increased values by 1 to 9 percent, depending on property type."

- See https://www.mutualaidstrategies.org/2012/02/18/the-1-dont-ride-public-transit/www.naccho.org/advocacy/testimony/loader.cfm?csModule=security

/getfile,PageID=193952. - See https://htaindex.cnt.org/#5.

- See https://blog.walkscore.com/category/walkability/#.VChhEkuFpLE.

- See https://www.governing.com/topics/public-justice-safety/gov-pedestrian-deaths-analysis.html.

- See https://www.bridgingthegapresearch.org/_asset/02fpi3/btg_street_walkability_FINAL_03-09-12.pdf.

- See https://www.governing.com/topics/urban/gov-most-walkable-cities.html.

- See https://www.fta.dot.gov/newsroom/news_releases/12286_16007.html.

- See https://www.washingtonmonthly.com/features/2010/1011.doherty-leinberger.html.

Articles may be reprinted if Communities & Banking and the author are credited and the following disclaimer is used: "The views expressed are not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston or the Federal Reserve System. Information about organizations and upcoming events is strictly informational and not an endorsement."

About the Authors

About the Authors

Scott Bricker, America Walks