2014 Series • No. 14–15

Research Department Working Papers

Vanishing Procyclicality of Productivity? Industry Evidence

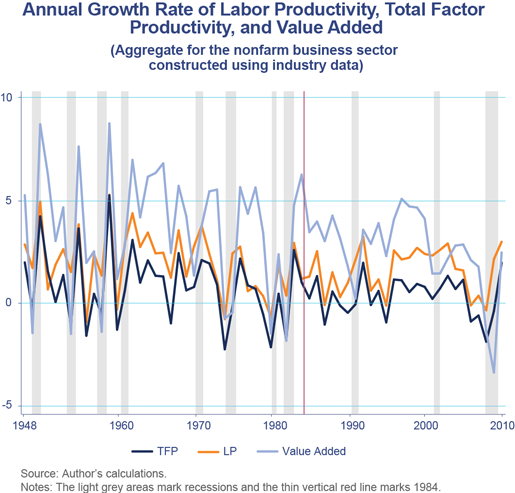

The robust performance of U.S. labor productivity (LP) early in the recovery from the Great Recession contrasts markedly with the sluggish growth of output, and even more with the lack of recovery in employment. This pattern has renewed interest in understanding why productivity has become much less procyclical in recent decades. This is an important topic because the cyclicality of productivity has implications for how we model business cycles, and our understanding of how they are propagated. The topic also has implications for monetary policy because it affects the trend-cycle decomposition and in turn the projection of trend growth as well as the assessment of the economy's output gap. A number of papers have investigated the aggregate time-series data and proposed mechanisms that may explain the observed changes. Those papers rely entirely on dynamic stochastic general equilibrium models. This study, in contrast, uses the cross-industry dimension as an alternative and complementary method for identifying the mechanisms that have led to the diminished procyclicality of productivity.

Key Findings

Key Findings

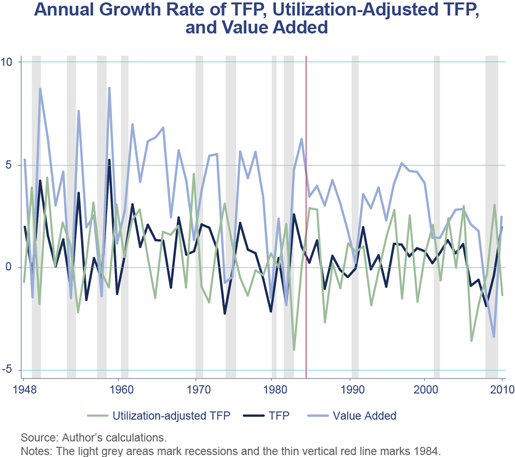

- For the overall nonfarm business sector, although the cyclicality of measured total factor productivity (TFP), which is labor productivity net of capital deepening, has fallen substantially since the mid-1980s, the cyclicality of technology shocks has changed little.

- By decomposing TFP into technology shocks and input utilization, this paper finds that TFP's correlation with inputs has fallen substantially to become negative since the mid-1980s and that the main reason for this decline is that technology shocks, which remain negatively correlated with inputs (that is, contractionary) in the short run, have come to account for a larger share of the fluctuations in TFP. Over the same period, the labor markets seem to have become more flexible, as the response of employment to technology shocks has decreased relative to the response of average hours per worker.

- The evidence does not appear to support the competing hypothesis that the reduction in the productivity-input correlation could be due to an increasing investment in intangible capital.

- The major contributor to the lower cyclicality of aggregate productivity is declines in within-industry cyclicality of productivity, especially in the service industries, whose share of total employment and output has increased noticeably since the mid-1980s.

Exhibits

Exhibits

Implications

Implications

The fact that employment has become less responsive than hours per worker to technology shocks since the mid-1980s can be explained by the finding that such shocks have become more persistent. It is inconsistent, however, with the explanation based purely on lower hiring and firing costs.

To the extent that we believe these findings constitute reasonable evidence of greater flexibility in the labor market, which is a structural change and should therefore be long lasting, these findings imply that policymakers should down-weight the performance of productivity during downturns in their estimates of the underlying trend growth rate.

Abstract

Abstract

Labor productivity (LP) in the United States has gone from being procyclical to acyclical since the mid-1980s. Using industry-level data, this paper first shows that total factor productivity (TFP), which is LP net of capital deepening, has also become much less correlated with output as well as inputs over the same period. Moreover, the bulk of the decline in aggregate TFP's cyclicality is attributable to service industries. This paper then uses the industry data to investigate the reasons for the change in the cyclicality of productivity. By decomposing TFP into technical change and input utilization, it finds that TFP's correlation with inputs has fallen and that the main reason for this decline is that technology shocks, which remain negatively correlated with inputs (that is, contractionary) in the short run, have come to account for a larger share of the fluctuations in TFP. Evidence suggests that this change is the result of more flexible labor markets together with more persistent technology shocks since the mid-1980s, causing firms to do less adjustment along the intensive margin. By comparison, the evidence does not appear to support the competing hypothesis that the reduction in the productivity-input correlation could be due to increasing investment in intangible capital.