Cross-Sectional Patterns of Mortgage Debt during the Housing Boom: Evidence and Implications

The reallocation of mortgage debt to low-income or marginally qualified borrowers plays a central role in many explanations of the early 2000s housing boom. This paper analyzes the mortgage boom with particular attention to how the debt was allocated with respect to income.

This is a substantially revised version of the original paper posted November 2016.

Key Findings

Key Findings

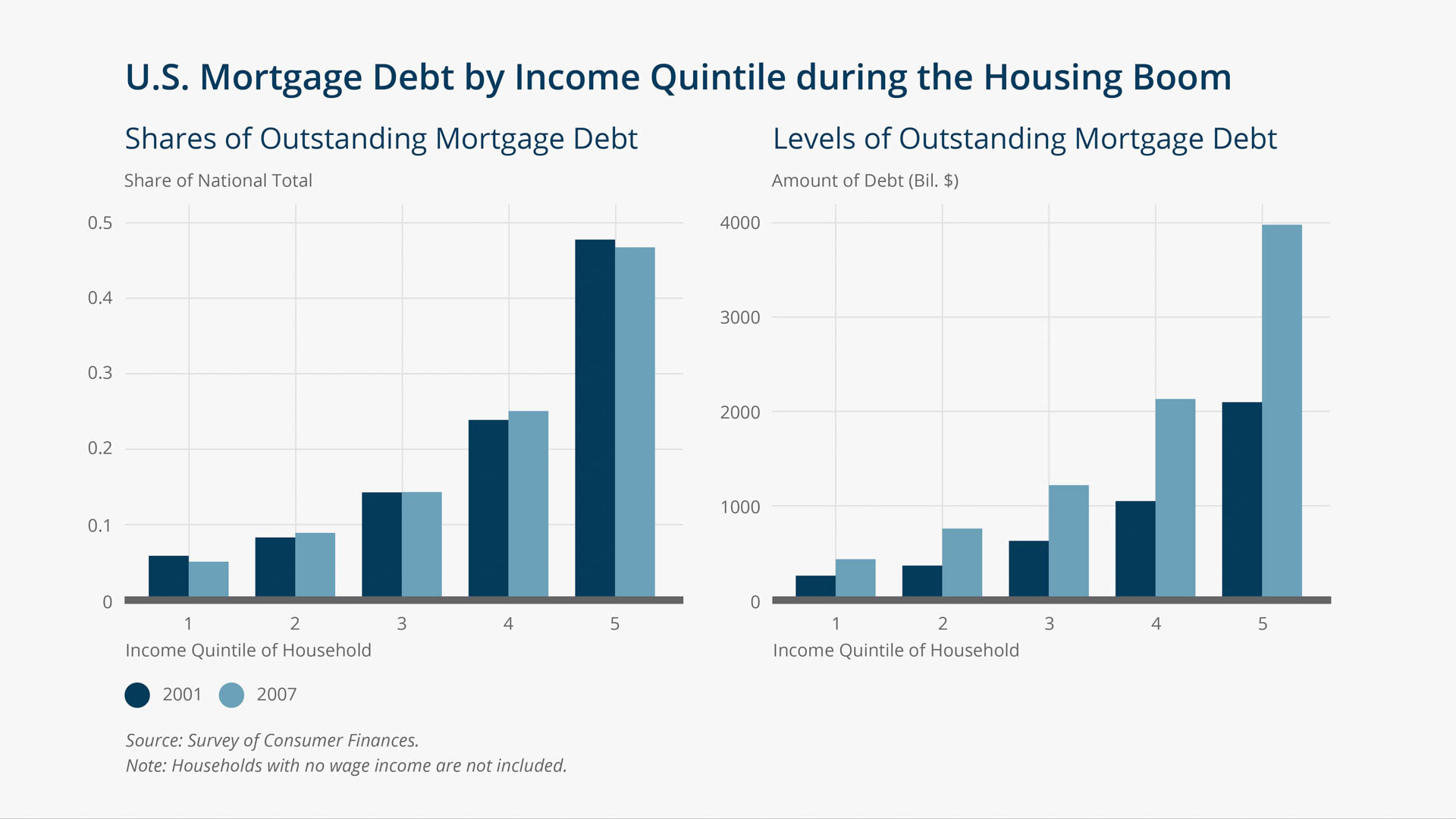

- There was no reallocation of mortgage debt toward low-income individuals during the housing boom. Low-income borrowing did grow rapidly during the boom, with much of this debt packaged into the subprime mortgage-backed securities that caused serious problems during the 2008 financial crisis. Yet borrowing by high-income individuals rose at similar rates, so the distribution of debt with respect to income remained stable over time. The same is true of the distribution of real estate assets.

- Because high-income borrowers tend to have more mortgage debt than do low-income borrowers, the equal percentage increases in debt across the income distribution meant that in dollar terms, most of the new mortgage debt went to the wealthy.

- Confusion in the academic literature has resulted from the common practice of using incomplete data on gross mortgage flows to infer changes in stocks of debt. For example, Mian and Sufi (2009) use data from the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) to argue that the allocation of mortgage credit changed fundamentally during the housing boom, in ways that channeled credit disproportionately to marginal or low-income borrowers. Yet HMDA data do not cover terminations, so they cannot reveal whether these newly originated mortgages reflect only higher transactional volumes in low-income areas or a true expansion of mortgage credit to more households. The authors of this paper, by combining flow and stock data to completely characterize the mortgage markets in question, find that it was higher transactional churn rather than a reallocation of mortgage credit that lay behind the original HMDA results. The finding that there was no relative credit expansion to low-income areas builds on Adelino, Schoar and Severino (2016), who use HMDA data to show that average amounts of mortgages grew by similar percentages in high- and low-income areas.

Exhibits

Exhibits

Implications

Implications

The broad-based increases in both mortgage debt and real estate assets have important implications for theories of the housing boom. A successful model of the boom must explain the stable cross-sectional distributions for debt and real estate assets, at the same time that the model explains the sharp increase in house prices. A theoretical section in this paper shows that to be consistent with the data, any explanation of the boom needs two elements: (1) an exogenous shock that increases expected house price growth or, alternatively, reduces interest rates and (2) financial markets that endogenously relax borrowing constraints in response to the shock. The data therefore imply that the large increase in subprime lending during the boom was not an exogenous shock driving house prices higher, but rather an endogenous response on the part of lenders to higher house prices. Lenders were happy to lend to low-income borrowers using subprime mortgages, because rising house values meant that these mortgages would be secured by rising value in the mortgages’ underlying collateral. In extending these subprime loans, lenders kept the distributions of mortgage debt and assets from tilting toward the rich.

Abstract

Abstract

In this paper, we use two comprehensive microdata sets to study how the distribution of mortgage debt evolved during the 2000s housing boom. We show that the allocation of mortgage debt across the income distribution remained stable, as did the allocation of real estate assets. Any theory of the boom must replicate these facts, and a general equilibrium model shows that doing so requires two elements: (1) an exogenous shock that increases expected house price growth or, alternatively, reduces interest rates and (2) financial markets that endogenously relax borrowing constraints in response to the shock. Empirically, the endogenous relaxation of constraints was largely accomplished with subprime lending, which allowed the mortgage debt of low-income households to increase at the same rate as that of high-income households.