Portfolio Choice with House Value Misperception

For the majority of households that own their primary residence, this home is their most important asset—it serves as a vehicle for savings and investment while also conferring shelter services. The house’s current value serves as a key determinant of the household’s other portfolio choices, as well as decisions related to consumption, savings, and retirement planning. By using data on self-reported (subjective) house values taken from individual households that participate in the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), and comparing this information to the zip code-level Core Logic Home Price Index, used as a proxy for the house’s market (objective) value, the authors show that over the 1984–2013 period, about half of the US households in this PSID sample systematically miscalculated the true current value of their home. Twenty-five percent of these households undervalued their house by 11 percent or more, while 25 percent overvalued their homes by at least 9 percent. Most studies on individual portfolio choice assume that households have accurate knowledge of their house’s market value, and thus do not consider how inaccurate beliefs about house values may skew other portfolio choices. By accounting for house value misperception and the role it may play in the household’s other financial decisions, the authors extend the portfolio choice model with transaction costs proposed in Grossman and Laroque (1990) and extend Alvarez, Guiso, and Lippi (2012) by incorporating uncertainty in the price of housing (a durable good) as it relates to choices for both housing and nonhousing consumption.

Key Findings

Key Findings

- On average, house value misperception is countercyclical to the housing market: those households that purchased a home during periods when house prices were declining tend to underestimate the value of their home, while households that bought a home during periods of positive house price growth tend to overestimate the value of their home.

- Subjectively determined house values, whether underestimated or overestimated, tend to persist for about six or seven years, on average, then the level of misperception reverts to zero, suggesting that households do eventually update their knowledge of the home’s market value, albeit infrequently. This finding of mean reversion is contrary to earlier research that found house price misperception is positively correlated with longstanding tenure

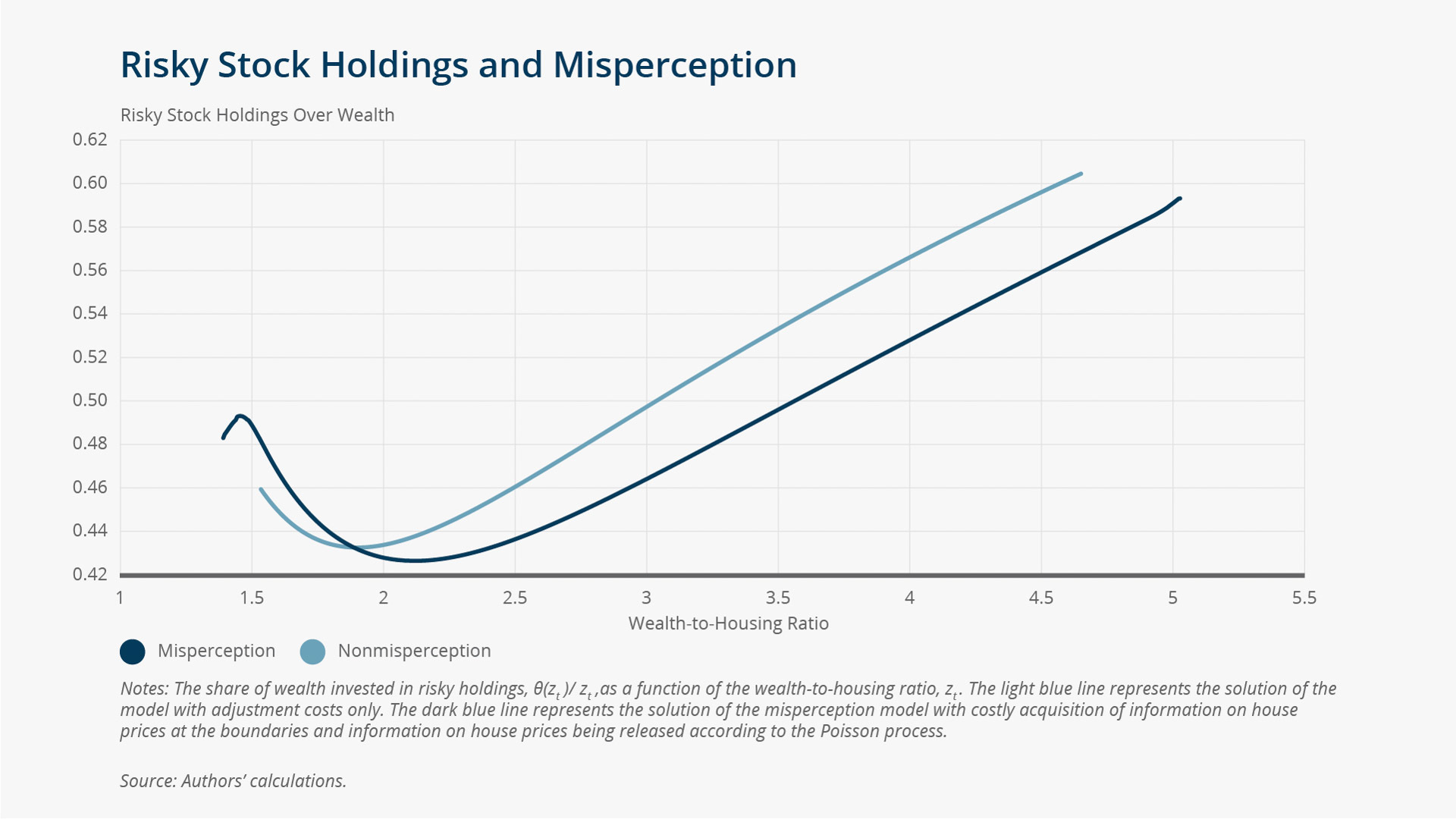

- The authors explain that house price misperception develops over time: a household knows the true market value of its home at the time of purchase, but it is costly to acquire information on the current market value, so over time the underestimation or overvaluation grows, and this misperception, rooted in rational inattention, influences other decisions on spending and investing. Assuming that housing is a risky investment, a larger perceived house value crowds out other risky investments, causing a decrease in the share of wealth allocated to stocks, the other risky asset in their model. The authors define stocks as stock holdings, individual retirement accounts, and annuities.

- A 1 percent increase in the measure of house price misperception lowers the average share of other risky assets by 1.76 percent for all households, an average decline of 4.56 for stock market participants, and an average decrease in nonhousing consumption of 2.72 percent. A 1 percent increase in overvaluation leads, on average, to a 7.91 percent decrease in the probability of investing in the stock market. In the absence of house value misperception, stock market holdings would be 3.7, 5.7, and 6.9 percent higher given a respective standard deviation in house price misperception of 5, 10, and 15 percent.

Exhibits

Exhibits

Implications

Implications

Households make spending, saving, and investment decisions based on their perceived level of total wealth, and continually optimize other nonhousing consumption and portfolio choices even when their housing stock remains the same. The authors’ model quantifies the effect that house value misperception has on the time-varying consumption and portfolio choices observed in the PSID data for US households. House value misperception causes many households, driven by risk aversion, to make suboptimal choices that can affect their amount of consumption and total wealth accumulation. While the results of this paper focus on partial equilibrium effects, future research might extend these findings by examining the general equilibrium effects that house value misperception has on asset prices or the gains in welfare that might result from eliminating the cost of obtaining accurate house price values.

Abstract

Abstract

Households systematically overvalue or undervalue their houses. We compute house value misperception as the difference between self-reported and market house values. Misperception is sizable, countercyclical, and persistent. We find that a 1 percent increase in house overvaluation results, on average, in a 4.56 percent decrease in the share of risky stock holdings for those households that participate in the stock market. We then build a rational inattention model in which households make decisions based on their perceived level of housing wealth. Numerical simulations generate the effects of house value misperception on the portfolio choices that we observe in the data.